Macrophages sweep up cellular debris and pathogens in order to thwart infection - sometimes even before the white blood cells, which are designed for that task.

Neutrophils, white blood cells, are "first responders" that are attracted to wounds by signaling molecules called reactive oxygen species (ROS) that activate a protein kinase. When neutrophils finish their work, inflammation is partly resolved through apoptosis, or cell suicide, and then macrophages arrive to clean up the infection.

But neutrophils can also elect to leave wounded tissue in a process known as reverse migration. Whether macrophages promote this mode of inflammation resolution is unclear.

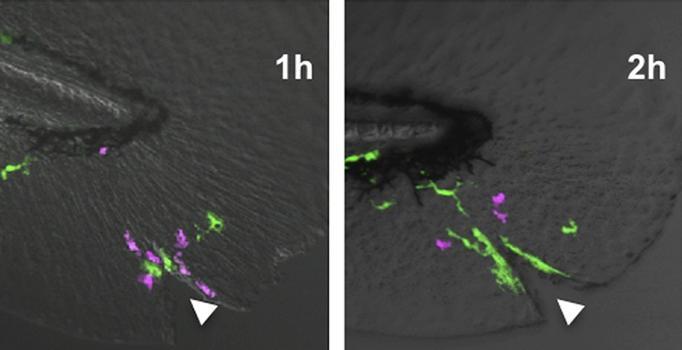

These time-lapse images show macrophages (green) contacting neutrophils (magenta) and chasing them away from a wound (arrowhead). Credit: Tauzin et al., 2014)

Taking advantage of transparent zebrafish larvae, Anna Huttenlocher and colleagues from the University of Wisconsin-Madison found that neutrophils were generally recruited to wounds before macrophages, but, once they arrived, macrophages often contacted neutrophils and appeared to shepherd them away from the damaged tissue. Neutrophils remained in wounds for longer times in zebrafish larvae lacking macrophages, the researchers discovered. Like neutrophils, macrophages were attracted to wounds by ROS and protein kinase signaling, and macrophages lacking the ROS-generating enzyme Nox2 were unable to migrate into wounds and induce the departure of neutrophils.

Interestingly, patients lacking the human equivalent of Nox2 suffer from recurring infections and exaggerated inflammation, a disorder known as chronic granulomatous disease. This new study suggests that one cause of the patients' symptoms may be the inability of macrophages to migrate to sites of inflammation to induce neutrophil reverse migration and inflammation resolution.

Published in The Journal of Cell Biology. Source: Rockefeller University Press

Comments