A research team gave old mice - the equivalent of 70- to 80-year-old humans - water containing an antioxidant known as MitoQ for four weeks and found that their arteries functioned as well as the arteries of mice with an equivalent human age of just 25 to 35 years.

The

MitoQ

antioxidant targets specific cell structures - mitochondria - and may be able to reverse some of the negative effects of aging on arteries, reducing the risk of heart disease, they conclude.

The researchers believe that MitoQ affects the endothelium, a thin layer of cells that lines our blood vessels. One of the many functions of the endothelium is to help arteries dilate when necessary. As people age, the endothelium is less able to trigger dilation and this leads to a greater susceptibility to cardiovascular disease.

“One of the hallmarks of primary aging is endothelial dysfunction,” said Rachel Gioscia-Ryan, a doctoral student in CU-Boulder’s Department of Integrative Physiology and lead author of the new study. “MitoQ completely restored endothelial function in the old mice. They looked like young mice.”

To trigger blood vessel dilation, the endothelium makes nitric oxide. As we age, the nitric oxide meant to cause dilation is increasingly destroyed by reactive oxygen species such as superoxide, which are produced by many components of our body’s own cells, including organelles called mitochondria.

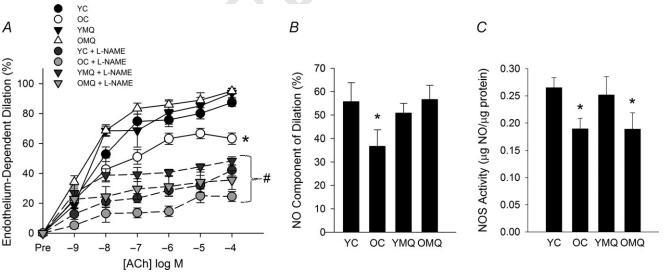

MitoQ restores nitric oxide-dependent endothelium-dependent dilation in old mice. A, endothelium-dependent dilation (EDD) dose responses to acetylcholine (ACh) in the absence/presence of the nitric oxide (NO) inhibitor N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) in carotid arteries of young (YC) and old (OC) control mice and young (YMQ) and old (OMQ) MitoQ-supplemented mice. Data are presented on a percentage basis to account for differences in vessel diameter among groups. (∗P < 0.05 vs. YC, main effect of group for dose response to ACh alone; #P < 0.05 within-group, dose response to Ach + L-NAME vs. dose response to ACh alone.) There were no group differences in the dose response to ACh + L-NAME. B, NO-dependent dilation (maxEDDACh–maxEDDACh+L-NAME) (∗P < 0.05 vs. YC). C, total NOS activity in the aorta (∗P < 0.05 vs. YC). All data are presented as means ± S.E.M. (n = 6–8/group). Credit:

doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268680

In a double-whammy, superoxide also reacts directly with the enzyme that makes nitric oxide, reducing the amount of nitric oxide being produced to begin with. All of this means less blood vessel dilation.

Even in the young and healthy, mitochondria produce superoxide, which is necessary in low levels to maintain important cellular functions. Superoxide is kept in check by the body’s own antioxidants, which combine with superoxide to make it less reactive and prevent oxidative damage to cells.

“You have this kind of balance, but with aging there is this shift,” said Gioscia-Ryan, who works in Professor Douglas Seals’ Integrative Physiology of Aging Laboratory at CU-Boulder. “There become way more reactive oxygen species than your antioxidant defenses can handle.”

That phenomenon, known as oxidative stress, occurs when the cells of older adults begin to produce too much superoxide and other reactive oxygen species. Mitochondria are a major source of superoxide in aging cells. The increased superoxide not only interacts with nitric oxide and the endothelium, but can also attack the mitochondria themselves. The damaged mitochondria become increasingly dysfunctional, producing even more reactive oxygen species and creating an undesirable cycle.

Past studies have looked at whether taking antioxidant supplements long term could improve vascular function in patients with cardiovascular disease by restoring balance to the levels of superoxide, but they’ve largely shown that the strategy isn’t effective.

This new study differs because it uses an antioxidant that specifically targets mitochondria. Biochemists manufactured MitoQ by adding a molecule to ubiquinone (also known as coenzyme Q10), a naturally occurring antioxidant. The additional molecule makes the ubiquinone become concentrated in mitochondria.

“The question is, ‘Why aren’t we all just taking a bunch of vitamin C?” Gioscia-Ryan said. “Scientists think that, taken orally, antioxidants like vitamin C aren’t getting to the places where the reactive oxygen species are being made. MitoQ basically tracks right to the mitochondria.”

The findings of the study indicate that the strategy of specifically targeting the mitochondria may be effective for improving the function of arteries as we age. In addition to improving endothelial function, the MitoQ treatment increased levels of nitric oxide, reduced oxidative stress and improved the health of the mitochondria in the arteries of old mice.

Citation: Rachel A Gioscia-Ryan, Thomas J LaRocca, Amy L Sindler, Melanie C Zigler, Michael P Murphy, Douglas R Seals, 'Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant (MitoQ) ameliorates age-related arterial endothelial dysfunction in mice', J Physiol March 24, 2014, doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268680

Comments