There is a discovery out there that has shown some success

with multiple sclerosis, with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS - Lou Gehrig's

Disease), and has even improved the function of aging hearts – but despite all

that, you have probably never heard of it.

No, this is not a story about how a revolutionary breakthrough got bought up by

some giant corporation and stuck in a warehouse to protect their profits - it

is instead a story about how potentially good products may never see the light

of day for lots of reasons. It happens more often than you think.

In 2013, we covered a study on Science 2.0 which suggested a cure for

a mouse version of multiple sclerosis. A few weeks ago a study came out which showed improvements in the

arteries of old mice. This month Elsevier published a study showing improvements in ALS. Another study last year showed improvement in Inflammatory Bowel

Disease (IBD).

They all had one thing in common – an antioxidant called MitoQ.

*****

Antioxidants are widely criticized because some companies in the

supplements business are correlating all kinds of health benefits without being

any more specific than that they contain 'antioxidants'. The $35 billion

organic food marketing machine claims locally-grown organic tomatoes have more

antioxidants and are therefore superior to regular-priced tomatoes. It's okay

to be skeptical of miracle health claims, I know I am.

But long before the hype, there was science happening and there still is today.

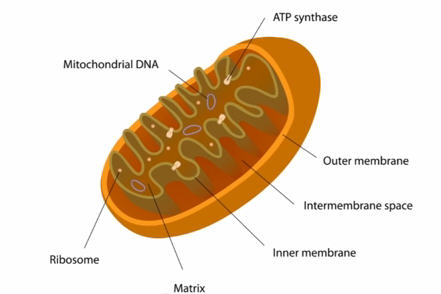

Antioxidants are intriguing because oxidative phosphorylation, our

metabolic pathway, impacts how the energy stored in food can be used within our

cells. As we age, mitochondria, an organelle in cells that uses oxygen to turn

carbohydrates and into energy, are less able to carry out their core function

of making adenosine triphosphate (ATP). When cells age, we age. Obviously, when

antioxidants talk about slowing aging it is going to get attention but, as GlaxoSmithKline

has discovered with resveratrol, proving it is difficult.

And some cynicism is warranted. Joe Mercola gushes about antioxidants, which is

a red flag for everyone in science, so how can the public separate the salesmanship

from the evidence? And if antioxidants impact how cells create energy, why not

just take more vitamin E, since antioxidant activity is its most important

benefit? Or vitamin C?

Why indeed. But there may be a bigger benefit than selling better health. Under the radar, away from CNN headlines about antioxidants and red

wine, scientists think a particular antioxidant may be the key to unlocking

answers to a lot of disease problems. And the

company behind it may never see anything for their efforts.

That takes us back to ALS, MS, heart disease and the MitoQ

at the heart of all those studies. It leads to an obvious question; why isn't

this in clinical trials? The answer is intriguing.

*****

MitoQ is appropriately named because it is a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant

descended from discoveries of Coenzyme Q that started in 1957. Coenzyme Q,

commonly called CoQ10, is a molecule made inside the mitochondria as

a component of the electron transport chain, to enable cellular

respiration and ATP. It’s oily and

sticky and that is fine inside mitochondria because it doesn't need to exit or

enter the membrane but coming from the outside, like with a supplement, it doesn’t penetrate very well. Because the antioxidants

didn’t actually get to mitochondria, people who took a CoQ10 supplement

didn't get much benefit, just like eating more fruits isn’t enough. It turns

out, a CoQ10 supplement only ends up having about 5 percent

bioavailability.

Credit: MitoQ.

A decade and a half ago, Professor Michael P. Murphy and Professor Robin A.J.

Smith of the University of Otago found a way to change that, by introducing a phosphonium

(salt) ion. You are aware that a lot of our bodily functions are electrical in

nature. Mitochondria are negatively charged and, as you know from school,

opposites attract. By adding a phosphonium group to the Coenzyme Q quinone

group they introduced a positive charge and discovered that the antioxidant

could still be quickly reduced to active quinol form by cells - but at levels

800-1200 times greater than CoQ10.

By doing so, Murphy and

Smith solved the puzzle as to why just eating more fruits didn't prevent cells

from becoming less efficient as we age – and perhaps how to fix that.

Accumulation of MitoQ10 into cells and mitochondria. MitoQ10 will first pass through the plasma membrane and accumulate in the cytosol driven by the plasma membrane potential (Dyp). From there it will be further accumulated several-hundred fold into the mitochondria, driven by the mitochondrial membrane potential (Dym). There it will be reduced to the active antioxidant ubiquinol. In preventing oxidative damage it will be oxidised to the ubiquinone which will then be re-reduced. ( Murphy, MP, Smith, RAJ, 'Targeting antioxidants to mitochondria by conjugation to lipophilic cations', ANNU REV PHARMACOL TOXICOL Volume: 47 Pages 629-656 2007)

There are about 200 conditions associated with mitochondria dysfunction and now

an antioxidant could be delivered directly into the mitochondria at levels that

were really meaningful.

For obvious reasons, they got patents on it, and research

continued. Clinical trials began. Optimism was high.

*****

Clinical trials are almost as old as society itself. There is a clinical trial

in The Bible (the Book of Daniel) but a more famous example is recent, when James

Lind used a clinical trial to show that citrus fruit cured scurvy - a disease

that leads to open wounds, rotting teeth and lethargy, primarily in sailors - in

1747. Since then, clinical trials have become the norm.

We hear a lot about Phase II and Phase III and other terms when it comes to

clinical trials so here is a short primer. Research is often done on animal

models and, if the results are promising, they will go to a clinical trial. All

clinical trials share a few traits in common - informed consent, statistical

power and a placebo group. A Phase I trial is looking for side effects that

haven't been found in animal tests and to figure out dosing. If things look

promising, as in it could be a commercial product, a Phase II trial recruits

larger numbers to really see that it works, that there are no side effects, and

that it is better than a placebo.

Phase III is where things get really exciting

because it compares the new treatment with the best currently available

treatment. In today’s drawn out regulatory environment, a Phase III trial will

often be an exit for a small company because conducting it requires a lot of

money and a larger company may be confident enough in its potential that they

are willing to pay for the product right now.

Trials are absolutely required to get government approval and what many people

do not realize is that, while the government makes the rules about how trials

are conducted, companies have to pay for them. "Industry-funded" is

the biggest misnomer among critics of science - all studies are industry-funded by law. You can't sell your drug unless

you first prove it is safe and does something useful, the local pharmacy cannot

be your lab and taxpayers shouldn't have to pay to find out if something is

safe.

Trials are expensive and so no company undertakes them unless they are convinced they have a winner. The risk/reward ratio is lopsided but someone has to be adventurous enough take a chance.

That’s where venture capital comes in.

MitoQ was exciting and so a company named Antipodean Pharmaceuticals raised

money and bought up the patents. The investors were intrigued by its possible

benefits for Parkinson's Disease. It did well in studies, until the Phase

II results didn't show the outcome they were looking for.

Venture capitalists immediately lost interest.

That's not a knock on VCs - VCs see a lot of losses before they see any wins

and they are a huge boon to society and especially drug discovery. But when an

investment doesn't work they check out, for one reason that makes sense to

everyone - the clock is still ticking on the patent.

A company that has a product that doesn't meet expectations in a Phase II trial

may have a great thing on their hands somewhere else - but they are

not going to own the patent for long to be able to start over. Expecting

venture capitalists to spend a lot of money proving the worth of a

compound only to lose it and then reset, start all over and pay for new

trials is unrealistic.

But sometimes products fail in a clinical trial and then have other benefits. Viagra is

a good example of a product that didn’t succeed with its original target but was

found to have a benefit elsewhere. MitoQ had that too - it actually seemed to

work for aging and all those studies had shown MitoQ was

safe. Murphy and Smith got a patent for a "Lipophilic

cation-mitochondrially targeted antioxidant compositions for skin care" in

2009.

Today,

the MitoQ compound is being marketed by a company fittingly called MitoQ. They

sell supplements and skin care and avoid any discussion of medical uses because

regulatory bodies frown on that sort of thing when there are no clinical

trial results. But the animal model research is right there, it’s hard to miss. They have to be at least a

little excited about that.

I contacted MitoQ CEO Greg Macpherson to ask the obvious questions about how so

much research is still finding results - and if MitoQ is ever going to see any

money from it.

He says they are thrilled that it’s still being studied extensively. " I

also think the research coming out from various sources on issues relating to

“broad spectrum” antioxidants is very interesting. We now know that free

radicals have beneficial effects as well - like helping the body identify and

remove cells that are infected or unhealthy or to capture the benefits of

exercise in terms of breaking down and rebuilding new muscle. Broad spectrum

antioxidants appear to negate these positive “pro-oxidant” signaling

mechanisms. Something a targeted antioxidant like MitoQ, that goes into the

mitochondria within minutes, avoids."

I asked him if, given the volume of studies coming out showing positive

results in animal models, if perhaps creative people were self-experimenting

and using the supplements off-label for conditions they read about in studies.

He wasn't biting on that but if you search the Internet, people with MS

claim it helps, people with heart disease say it helps. And the clinical

trials showed it can't hurt.

No matter what results happen in animal models this year or next, with only 10

years of patent life remaining and such a lopsided risk/reward landscape for

drug development, the window is too small to turn MitoQ into another Glaxo. But

Macpherson is surprisingly upbeat regardless of that.

"MitoQ has incredible potential to help with lots of conditions associated

with oxidative stress imbalances and mitochondrial dysfunction, be it primary

or secondary to another condition. When we optimize mitochondrial function we

are improving the energy production in a cell and more energy means that the

cell is able to function optimally. Because our bodies are essentially self

repairing machines, when we get optimal cellular function we are providing the

energy a cell needs to repair itself. MitoQ also slows the oxidative stress

related damage that occurs slowly to our cells over the years. This includes

damage to DNA, telomeres and other cellular machinery.”

And if things do change in the regulatory future?

"Someone in the future is going to make a

killing going back through all these compounds and cross checking their

activity vs the various genotypes to assess function and toxicity profiles."

In the meantime, researchers continue to study MitoQ. Macpherson is happy about that, obviously they believe in it, and a page on their site even carries links to the latest research.

“The science is very strong and safety is well established so we are regularly approached by research scientists and universities around the world who want to investigate it’s effects in the various disease models they are studying. We have made MitoQ available for this research and there is some amazing research being undertaken by leading scientists that will surface over the next few years.”

So Mitoq was a loss for VCs but may still end up being a win for society.

Comments