The dwarf planet Makemake is about two thirds of the size of Pluto and farther from the Sun - but closer than Eris, the most massive so-called dwarf planet in the Solar System after the confusing reconfiguration by the International Astronomical Union that said Pluto was not a planet but then was, only a special non-planet along with others.

Like Eris, but unlike Pluto, Makemake has no atmosphere, making it even less sensical as a planet.

To determine this, researchers combined multiple observations using three telescopes at ESO's La Silla and Paranal observing sites in Chile; the Very Large Telescope (VLT), New Technology Telescope (NTT), and TRAPPIST (TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope) -- with data from other small telescopes in South Americato visualize Makemake as it passed in front of a distant star.

"As Makemake passed in front of the star and blocked it out, the star disappeared and reappeared very abruptly, rather than fading and brightening gradually. This means that the little dwarf planet has no significant atmosphere," says team leader Jose Luis Ortiz of Instituto de Astrofisica de Andalucia, CSIC, in Spain. "It was thought that Makemake had a good chance of having developed an atmosphere -- that it has no sign of one at all shows just how much we have yet to learn about these mysterious bodies. Finding out about Makemake's properties for the first time is a big step forward in our study of the select club of icy dwarf planets."

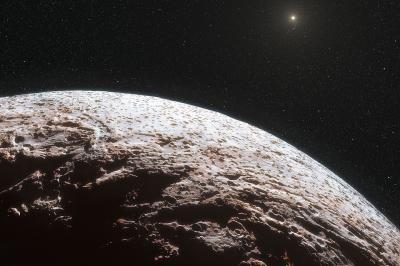

Artistic conception of Makemake shows the surface of the distant dwarf planet Makemake. This dwarf planet is about two thirds of the size of Pluto, and travels around the Sun in a distant path that lies beyond that of Pluto, but closer to the Sun than Eris, the most massive known dwarf planet in the Solar System. Makemake was expected to have an atmosphere like Pluto, but this has now been shown to not be the case. (Photo Credit: ESO/L. Calçada/Nick Risinger (skysurvey.org))

Makemake's lack of moons and its great distance from us make it difficult to study, and what little is known is only approximate. The team's new observations add detail to our view of Makemake, like determining its size more accurately, putting constraints on a possible atmosphere and estimating the dwarf planet's density for the first time. They have also allowed the astronomers to measure how much of the Sun's light Makemake's surface reflects -- its albedo. Makemake's albedo, at about 0.77, is comparable to that of dirty snow, higher than that of Pluto, but lower than that of Eris.

It was only possible to observe Makemake in such detail because it passed in front of a star, a stellar occultation. These rare opportunities are allowing astronomers for the first time to find out a great deal about the sometimes tenuous and delicate atmospheres around these distant, but important, members of the Solar System, and providing very accurate information about their other properties.

Occultations are particularly uncommon in the case of Makemake, because it moves in an area of the sky with relatively few stars. Accurately predicting and detecting these rare events is extremely difficult and the successful observation by a coordinated observing team, scattered at many sites across South America, ranks as a major achievement.

"Pluto, Eris and Makemake are among the larger examples of the numerous icy bodies orbiting far away from our Sun," says Ortiz. "Our new observations have greatly improved our knowledge of one of the biggest, Makemake -- we will be able to use this information as we explore the intriguing objects in this region of space further."

Comments