New research could lead to a better understanding of how the brain works in people with autism. Little is known about the cognitive processes involved.

Researchers from Monash University and Deakin University looked at new hypotheses of autism that focused on the way in which the brain combines new information from its senses with prior knowledge about the environment. Using the 'rubber-hand' illusion, the researchers examined how adults with autism experienced 'ownership' of a fake prosthetic hand.

In the 'rubber-hand' illusion, one of the subject's hands is placed out of sight, while a rubber hand sits in front of them. By stroking the fake hand at the same time as the visible real one, the subject can be convinced the fake hand is theirs.

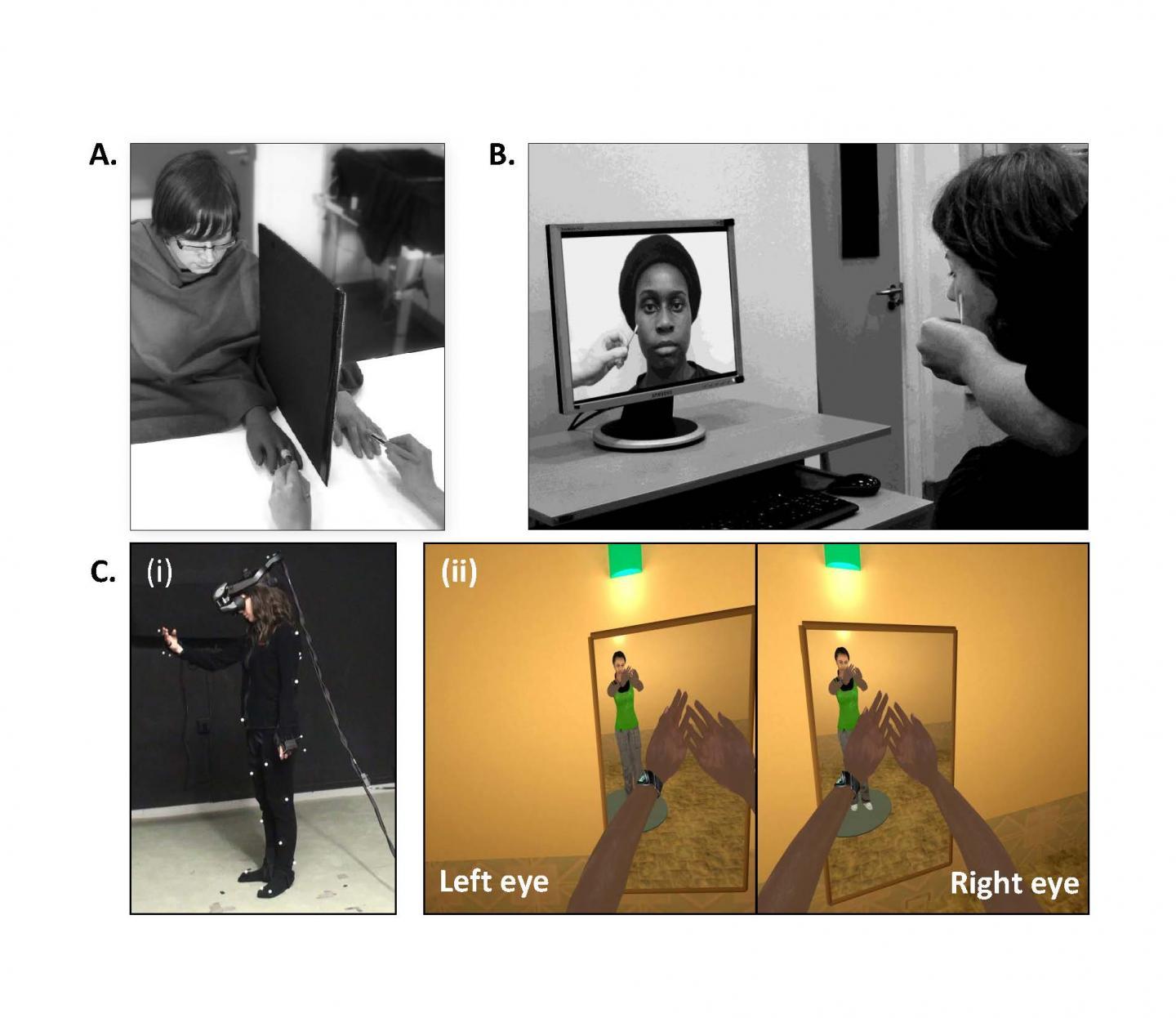

An example of the Rubber Hand Illusion. (A) The Rubber Hand Illusion: Light-skinned Caucasian participants observe a dark-skinned rubber hand being stimulated in synchrony with their own unseen hand. This elicits a shift of body ownership to incorporate the other-race limb. Adapted and reproduced, with permission, from reference [9]. (B) The Enfacement Illusion: Participants viewed the face of a racial outgroup member being stimulated in synchrony with their own to induce a sense of ownership over the observed face (see reference [14]). (C) Immersive Virtual Reality: (i) A participant wears a wide field-of-view stereo head-tracked head-mounted display and a motion capture suit for real-time body tracking. (ii) This is the participant's view of the situation, whereby she can see her virtual body both directly and reflected in the mirror, in stereo as shown. The body she sees could be dark-skinned, light-skinned, or purple; in this case, the virtual body is dark skinned whereas she is light skinned. Photo Credit: Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Maister et al.

Ph.D. student Colin Palmer from Monash University's School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies said, "It is still unclear what is happening differently in the brain to produce the social, sensory and other difficulties that individuals with autism can face. We are testing a new type of theory, which implicates the brain's capacity for making predictions about its own sensory input. Autism may be related to problems with making those predictions sensitive to the wider context. This means that new sensory input is interpreted out of context, making it difficult to understand the world and to generalize to new situations."

Following their experience of the illusion, participants were then asked to reach out and grasp an object with their hand. The researchers found these hand movements were disrupted by their previous experience of the illusion. People low in autism-like traits were the most sensitive to the illusion.

"People with autism experienced the typical perceptual effects of the rubber-hand illusion, but, unusually, we find that they are more resistant to the effects of the illusion on arm movement," Palmer said.

The results suggest that in autism the brain may draw less on background information from the surrounding environment when performing movement than for someone not on the spectrum.

"The study suggests that individuals may differ in how their brains draw upon contextual information when perceiving and interacting with the world," Palmer said. "This could contribute to sensory and movement difficulties, which are commonly experienced in autism."

Future research will look at how this type of processing difference may contribute to social behavior, given that our understanding of social situations (such as other people's thoughts and intentions) often depends on taking into account the broader context.

The study was a collaboration between the Cognition and Philosophy Lab at Monash University, the Cognitive Neuroscience Unit at Deakin University, and the Monash Alfred Psychiatry research centre.

Comments