Eric Tremblay from EPFL in Switzerland says the first iteration of the telescopic contact lens--which magnifies 2.8 times--was announced in 2013. Since then the scientists behind the DARPA-funded project have been fine-tuning the lens membranes and developing accessories to make the eyewear smarter and more comfortable for longer periods of time, and thus more usable in every day life.

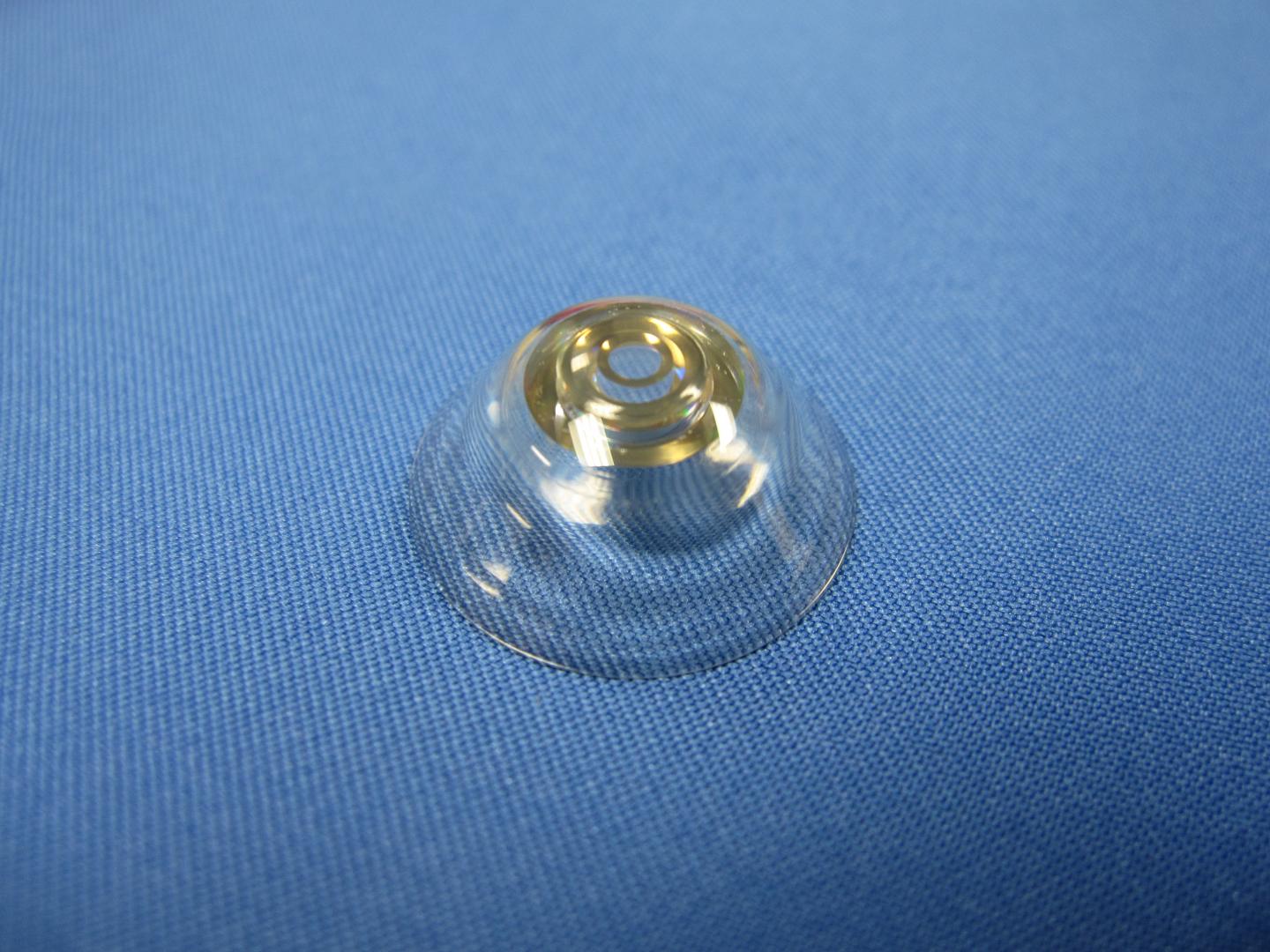

The contacts work by incorporating a very thin reflective telescope inside a 1.55mm thick lens. Small mirrors within bounce light around, expanding the perceived size of objects and magnifying the view, so it's like looking through low magnification binoculars.

Close-up view of the latest prototype of the telescopic contact lens. Courtesy of EPFL.

At this time, the telescopic contacts are made using a rigid lens known as a scleral lens--larger in diameter than the typical soft contacts you might be used to and valuable for special cases, such as for people with irregularly shaped corneas. Although large and rigid, scleral lenses are safe and comfortable for special applications, and present an attractive platform for technologies such as optics, sensors, and electronics like the ones in the telescopic contact lens, says Tremblay.

The final lenses are made from several precision cut and carefully assembled pieces of plastics, aluminum mirrors, and polarizing thin films, along with biologically safe glues.

Since the eye needs a steady supply of oxygen, the scientific team has spent the last couple of years making the lenses more breathable--a critical requirement. To achieve oxygen permeability, they are incorporating tiny air channels roughly 0.1mm wide within the lens to allow oxygen to flow around and underneath the complex and normally impermeable optical structures to get to the cornea.

Image quality and oxygen permeability in the lenses are ongoing challenges and objects of research, but results are improving as the mechanical and manufacturing processes are refined and better understood, say the scientists. The prototypes shown at AAAS demonstrate the latest versions.

"We think these lenses hold a lot of promise for low vision and age-related macular degeneration (AMD)," says Tremblay, an EPFL researcher whose collaborators include Joe Ford at the University of California, San Diego, and others at Paragon Vision Sciences, Innovega, Pacific Sciences and Engineering, and Rockwell Collins. "It's very important and hard to strike a balance between function and the social costs of wearing any kind of bulky visual device. There is a strong need for something more integrated, and a contact lens is an attractive direction. At this point this is still research, but we are hopeful it will eventually become a real option for people with AMD."

Comments