Politicians often say one thing in public and other things in private. That is no surprise, people in all jobs do the same thing.

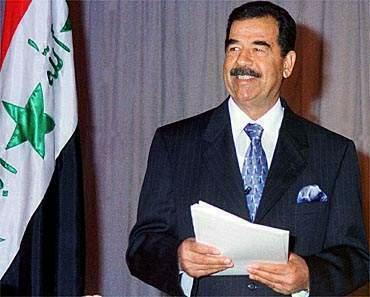

Saddam Hussein, the genocidal former dictator of Iraq, has left a legacy most despots do not; he recorded so many of his private conversations that political scientists can analyze what he said in private and compare those to his public statements. Their conclusion; he believed what he said.

Very bad man, but he believed in his badness.

Credit: Mid-East Wire

Writing in Research and Politics, the authors note that thousands of audio recordings of Hussein's private meetings and telephone conversations were discovered by US forces after the 2003 invasion. Stephen Dyson, Associate Professor of Foreign Policy and International Relations at the University of Connecticut, and Alexandra Raleigh, a doctoral student in political science from the University of California-Irvine, analyzed transcripts of these discussions.

"While Saddam spoke extensively in public speeches during his decades in power, there had [been] few means by which to judge whether these were manipulative communications – until now," Dyson and Raleigh Say.

The researchers collected Hussein's public speeches and interviews on international affairs from 1977-2000, which produced a data set of 330,000 words. From the private transcripts, they gleaned a further set of 58,000 words. Dyson and Raleigh deployed a technique called automated content analysis, looking for markers of conflict, control and complexity among these word sets using well-established coding schemes. The transcripts available cover major national security matters, such as the US, Israel, the Iran-Iraq war, the first Persian Gulf War, and the United Nations sanctions regime.

Using a separately constructed reference group of world leaders for comparison, the researchers found public and private beliefs were in accord in all areas they examined except for conceptual complexity. Hussein held a resolutely hostile image of the political universe and a preference for non-cooperative strategies. He exhibited public confidence in his ability to shape events, and this was even more pronounced in private. In terms of his views on his three greatest enemies – the US, Iran and Israel – his beliefs about these states bore a striking similarity to his overall worldview: hostile images of self and other, high perceptions of control, and variable levels of complexity. Hussein privately perceived lower ability to control Israeli actions in private than in public. In the case of the US, he described it in more hostile terms when speaking publically; when discussing policy behind closed doors; his words indicate a greater conceptual complexity about the US.

The authors conclude that in Saddam Hussein's case, we can see a similar political actor in public and private most of the time.

"Researchers armed with content analysis technologies now have some evidence showing that beliefs revealed publicly match those concealed privately," Dyson and Raleigh say. "These are baseline propensities Saddam exhibited when thinking about the world, and diagnosing a worldview is far from foreseeing an action on a specific date directed at a specific target."

Impression management could be taking place in private discussions as well as in public, so a third set of even more private data – for example from a diary – would make for interesting comparison. Other major political figures, such as Hitler, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon and Kissinger, left transcripts of private deliberations, which would be ideal for a similar analytical approach. The authors suggest politics researchers will have much to mull over in the finding that public speech is sincere and predictive of private beliefs, rather than manipulative.

Comments