Researchers have cracked a code that governs infections by the common cold and polio viruses.

The code was known, it was 'hidden in plain sight' in the sequence of the ribonucleic acid (RNA) that makes up this type of viral genome but its meaning had not been unlocked. Now, researchers have found that jamming the code can disrupt virus assembly. Stopping a virus assembling can stop it functioning and therefore prevent disease.

Single-stranded RNA viruses are the simplest type of virus and were probably one of the earliest to evolve. However, they are still among the most potent and damaging of infectious pathogens.

Rhinovirus (which causes the common cold) accounts for more infections every year than all other infectious agents put together (about 1 billion cases), while emergent infections such as chikungunya and tick-borne encephalitis are from the same ancient family. Other single-stranded RNA viruses include the hepatitis C virus, HIV and the winter vomiting bug norovirus.

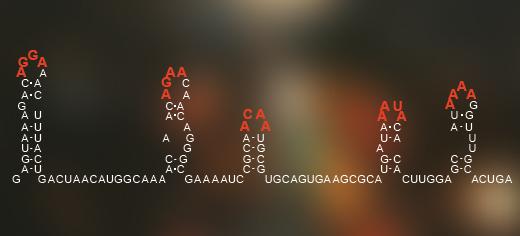

A code hidden in the arrangement of the genetic information of single-stranded RNA viruses tells the virus how to pack itself within its outer shell of proteins. Credit: University of Leeds

Professor Peter Stockley, Professor of Biological Chemistry in the University of Leeds' Faculty of Biological Sciences, who led the study, said, "If you think of this as molecular warfare, these are the encrypted signals that allow a virus to deploy itself effectively. Now, for this whole class of viruses, we have found the 'Enigma machine'--the coding system that was hiding these signals from us. We have shown that not only can we read these messages but we can jam them and stop the virus' deployment."

The breakthrough was the result of three stages of research.

- In 2012, researchers at the University of Leeds published the first observations at a single-molecule level of how the core of a single-stranded RNA virus packs itself into its outer shell--a remarkable process because the core must first be correctly folded to fit into the protective viral protein coat. The viruses solve this fiendish problem in milliseconds. The next challenge for researchers was to find out how the viruses did this.

- University of York mathematicians Dr Eric Dykeman and Professor Reidun Twarock, working with the Leeds group, then devised mathematical algorithms to crack the code governing the process and built computer-based models of the coding system.

- In this latest study, the two groups have unlocked the code. The group used single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy to watch the codes being used by the satellite tobacco necrosis virus, a single stranded RNA plant virus.

Dr. Roman Tuma, Reader in Biophysics at the University of Leeds, said, "We have understood for decades that the RNA carries the genetic messages that create viral proteins, but we didn't know that, hidden within the stream of letters we use to denote the genetic information, is a second code governing virus assembly. It is like finding a secret message within an ordinary news report and then being able to crack the whole coding system behind it.

"This paper goes further: it also demonstrates that we could design molecules to interfere with the code, making it uninterpretable and effectively stopping the virus in its tracks."

Professor Reidun Twarock, of the University of York's Department of Mathematics, said, "The Enigma machine metaphor is apt. The first observations pointed to the existence of some sort of a coding system, so we set about deciphering the cryptic patterns underpinning it using novel, purpose designed computational approaches. We found multiple dispersed patterns working together in an incredibly intricate mechanism and we were eventually able to unpick those messages. We have now proved that those computer models work in real viral messages."

The next step will be to widen the study into animal viruses. The researchers believe that their combination of single-molecule detection capabilities and their computational models offers a novel route for drug discovery.

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The research was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC). Professor Twarock's Royal Society Leverhulme Trust Senior Research Fellowship and Dr Dykeman's Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship also supported the work.

Comments