Damage assessments from environmental hazards are always a challenge because of the competing constituencies pulling on science and the fuzzy nature of estimates. After the 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the Obama administration was editing science reports to reflect its goals, environmentalists were raising money claiming earth was ruined and using wild guesses for damage, and BP lobbyists were mitigating penalties behind the scenes by claiming it wasn't so bad.

What about possibly 2 million barrels of oil that are still down there? Are they a hazard? Where did they go?

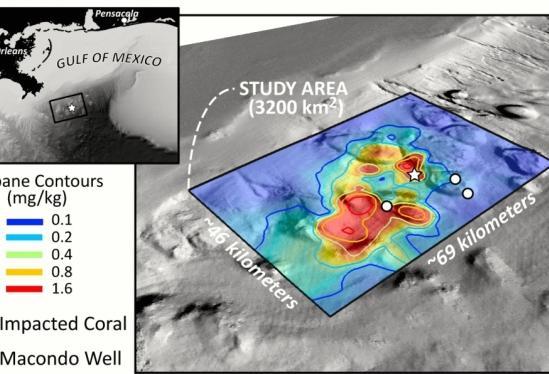

By analyzing data from more than 3,000 samples collected at 534 locations over 12 expeditions, they identified a 1,250-square-mile patch of the deep sea floor upon which 2 to 16 percent of the discharged oil was deposited. The fallout of oil to the sea floor created thin deposits most intensive to the southwest of the Macondo well. The oil was most concentrated within the top half inch of the sea floor and was patchy even at the scale of a few feet.

Hydrocarbon contamination from Deepwater Horizon overlaid on sea floor bathymetry, highlighting the 1,250 square mile area identified in the study. Credit: G. Burch Fisher

Researchers recently set out to describe a path the oil could have followed, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. They collated data from other agencies, the Natural Resource Damage Assessment process conducted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The Obama administration estimated the Macondo well's total discharge — from the spill in April 2010 until the well was capped that July — to be 5 million barrels.

The investigation focused primarily on hopane, a nonreactive hydrocarbon that served as a proxy for the discharged oil. Researchers analyzed the spatial distribution of hopane in the northern Gulf of Mexico and found it was most concentrated in a thin layer at the sea floor within 25 miles of the ruptured well, clearly implicating Deepwater Horizon as the source.

"Based on the evidence, our findings suggest that these deposits come from Macondo oil that was first suspended in the deep ocean and then settled to the sea floor without ever reaching the ocean surface," said co-author David Valentine, a professor of earth science and biology at UC Santa Barbara. "The pattern is like a shadow of the tiny oil droplets that were initially trapped at ocean depths around 3,500 feet and pushed around by the deep currents. Some combination of chemistry, biology and physics ultimately caused those droplets to rain down another 1,000 feet to rest on the sea floor."

The team were able to identify hotspots of oil fallout in close proximity to damaged deep-sea corals. According to the researchers, this data supports the previously disputed finding that these corals were damaged by the Deepwater Horizon spill.

"The evidence is becoming clear that oily particles were raining down around these deep sea corals, which provides a compelling explanation for the injury they suffered," said Valentine. "The pattern of contamination we observe is fully consistent with the Deepwater Horizon event but not with natural seeps — the suggested alternative."

While the study examined a specified area, the scientists argue that the observed oil represents a minimum value. They purport that oil deposition likely occurred outside the study area but so far has largely evaded detection because of its patchiness.

This image shows controlled burning of surface oil slicks during the Deepwater Horizon event.

(Photo Credit: David Valentine)

"This analysis provides us with, for the first time, some closure on the question 'Where did the oil go and how?' " said Don Rice, program director in the National Science Foundation's Division of Ocean Sciences. "It also alerts us that this knowledge remains largely provisional until we can fully account for the remaining 70 percent."

"These findings should be useful for assessing the damage caused by the Deepwater Horizon spill as well as planning future studies to further define the extent and nature of the contamination," Valentine concluded. "Our work can also help to assess the fate of reactive hydrocarbons, test models of oil's behavior in the ocean and plan for future spills."

Comments