Could Niacin Be Added To Glioblastoma Treatment?

Could Niacin Be Added To Glioblastoma Treatment?Glioblastoma, a deadly brain cancer, is treated with surgery to remove as much of the tumor as...

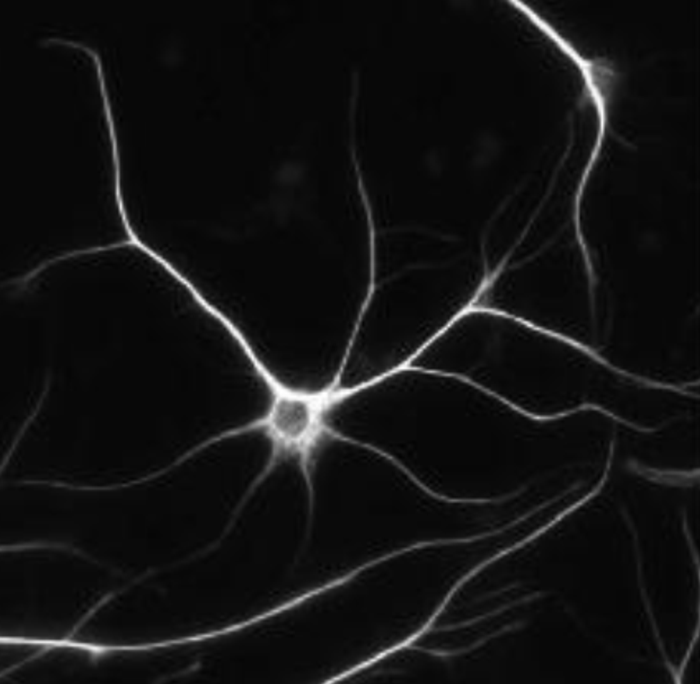

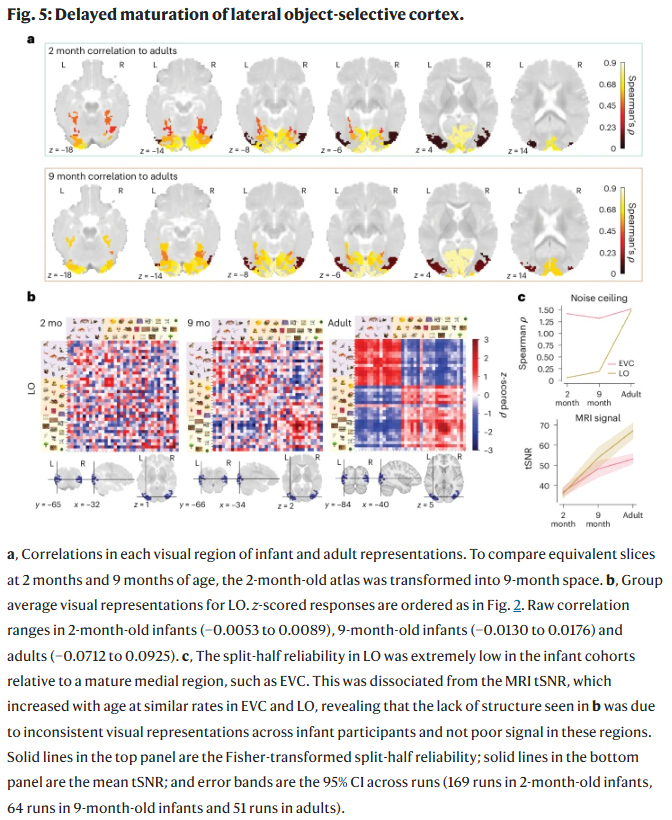

At 2 Months, Babies Can Categorize Objects

At 2 Months, Babies Can Categorize ObjectsAt two months of age, infants lack language and fine motor control but their minds may be understanding...

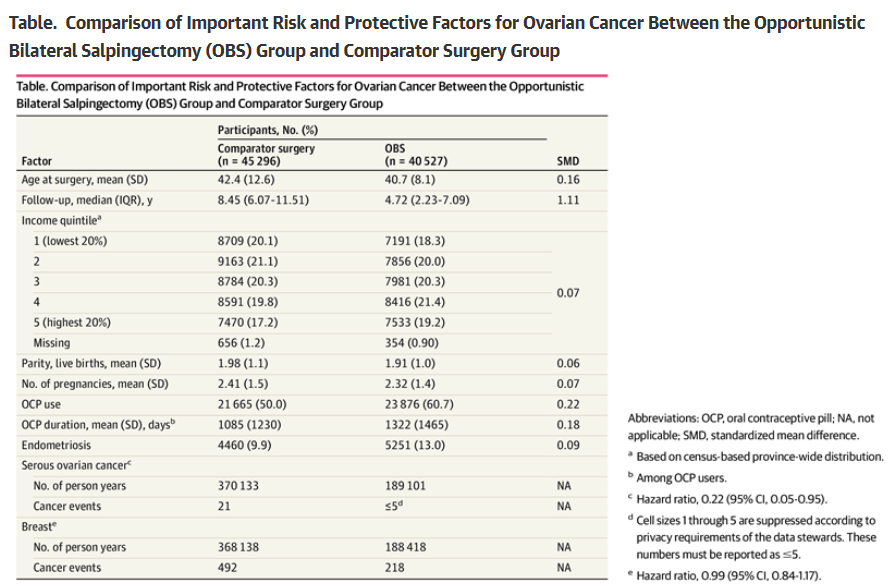

Opportunistic Salpingectomy Reduces Ovarian Cancer Risk By 78%

Opportunistic Salpingectomy Reduces Ovarian Cancer Risk By 78%Opportunistic salpingectomy, proactively removing a person’s fallopian tubes when they are already...

Environmental Activists Hate CRISPR - And They're Dooming People With HIV

Environmental Activists Hate CRISPR - And They're Dooming People With HIVExisting treatments control HIV but the immune system does not revert to normal. They is why people...