The underlying cloaking phenomenon is similar to the mirages seen ahead at a distance on a road on a hot day.

How did they do it? Ruopeng Liu, who developed a new algorithm for optimizing the metamaterials, and Chunlin Li. David R. Smith, William Bevan Professor of electrical and computer engineering at Duke and senior member of the research team, write in Science that after improving the metamaterials using Liu's new algorithm their latest cloaking device went from conception to fabrication in nine days, compared to the four months required to create their original, and more rudimentary, device. This will make it possible to custom-design unique metamaterials with specific cloaking characteristics, the researchers said.

"The difference between the original device and the latest model is like night and day," Smith said. "The new device can cloak a much wider spectrum of waves — nearly limitless — and will scale far more easily to infrared and visible light. The approach we used should help us expand and improve our abilities to cloak different types of waves."

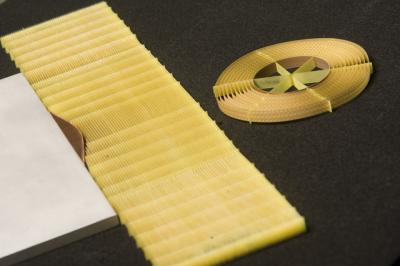

It doesn't look all that spectacular but in the world of metamaterials this is a big achievement. The new cloak with bump, left, and the prototype, right. Credit: Duke University Photography

Cloaking devices bend electromagnetic waves, such as light, in such a way that it appears as if the cloaked object is not there. In the latest laboratory experiments, a beam of microwaves aimed through the cloaking device at a "bump" on a flat mirror surface bounced off the surface at the same angle as if the bump were not present. Additionally, the device prevented the formation of scattered beams that would normally be expected from such a perturbation.

The underlying cloaking phenomenon is similar to the mirages seen ahead at a distance on a road on a hot day.

"You see what looks like water hovering over the road, but it is in reality a reflection from the sky," Smith explained. "In that example, the mirage you see is cloaking the road below. In effect, we are creating an engineered mirage with this latest cloak design."

Smith believes that cloaks should find numerous applications as the technology is perfected. By eliminating the effects of obstructions, cloaking devices could improve wireless communications, or acoustic cloaks could serve as protective shields, preventing the penetration of vibrations, sound or seismic waves.

"The ability of the cloak to hide the bump is compelling, and offers a path towards the realization of forms of cloaking abilities approaching the optical," Liu said. "Though the designs of such metamaterials are extremely complex, especially when traditional approaches are used, we believe that we now have a way to rapidly and efficiently produce such materials."

With appropriately fine-tuned metamaterials, electromagnetic radiation at frequencies ranging from visible light to radio could be redirected at will for virtually any application, Smith said. This approach could also lead to the development of metamaterials that focus light to provide more powerful lenses.

The newest cloak, which measures 20 inches by 4 inches and less than an inch high, is actually made up of more than 10,000 individual pieces arranged in parallel rows. Of those pieces, more than 6,000 are unique. Each piece is made of the same fiberglass material used in circuit boards and etched with copper.

The algorithm determined the shape and placement of each piece. Without the algorithm, properly designing and aligning the pieces would have been extremely difficult, Smith said.

The research was supported by Raytheon Missile Systems, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, InnovateHan Technology, the National Science Foundation of China, the National Basic Research Program of China, and National Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China.

Others members of the research team were Duke's Jack Mock, as well as Jessie Y. Chin and Tie Jun Cui from Southeast University, Nanjing, China.

Comments