Some states have also 'bundled' behavioral and physical health care, and that hasn't improved access or care for people with mental health issues. It isn't worse, that is the good news, but for the 400 percent increase in cost it isn't better - and demand became higher due to heightened anxiety and depression rates during and post the COVID-19 pandemic.

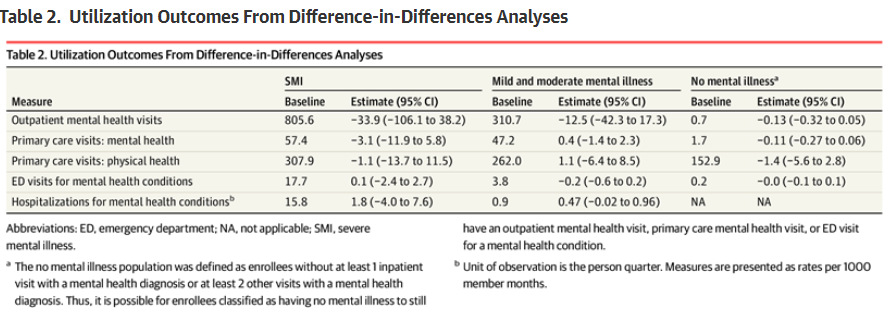

Writing in JAMA Health Forum, the article highlights that an administrative alteration read nice but did not drive enhancements in access, quality, and overall health outcomes for patients. The claims-based data and health outcomes were approximately 1.4 million Medicaid-covered patients across Washington’s 39 counties between 2014 and 2019. Washington state touts itself as a leader in integrated managed care to improve mental health treatment, so the large span of data let researchers evaluate metrics like mental health visits, instances of self-harm, and general quality of life indicators such as arrest rates, employment statuses, and homelessness.

“The surprising result was that nothing really changed,” said lead author John McConnell, Ph.D., director of the Oregon Health&Science University Center for Health Systems Effectiveness.

What might work? The article speculates that a change in payments from fee-for-service to compensating providers based on the overall patient population they serve might help, but people who are on subsidized health insurance already struggle to get access. Using patient demographics would put the 700,000 people who were unable to get insurance, or the poor who had limited doctors, back in the same position while everyone else remains stuck with government-mandated high costs.

Comments