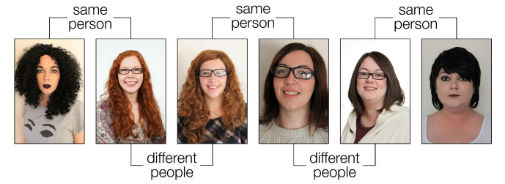

Perhaps it was ridiculous if keen reporters who knew Kent well did not figure it out, but for the most part even subtle disguises work well for most people, according to a new study. Something as minor as complexion changes or a hairstyle are enough to convince people that in a world of six billion people, a one in a million chance of seeing a person who looks like someone you know is not that bad.

In the study, participants were often fooled by disguises when asked to judge whether two photographs showed the same or different people. Disguises reduced the ability of participants to match faces by around 30%, even when they were warned that some of the people had changed the way they look. Participants were only able to see through disguises reliably when they knew the people in the images.

Credit: University of York

The models recruited for the study were given plenty of time and resources with which to change their appearance. Many used make-up, changed their hair color and style, and some grew or got rid of facial hair. To ensure maximum effort, a financial incentive was introduced with a prize for the model whose disguise fooled the most participants.

Props like hats or dark glasses were not allowed as they are prohibited in real-life security settings.

The researchers also compared the effectiveness of two different methods of disguise:

Impersonation disguise - or trying to look like someone else - is sometimes used by people attempting to travel using a stolen passport or in cases of identity theft.

Evasion disguise – trying not to look like yourself - might be used in witness protection programmed or by undercover police, as well as by criminal suspects on the run from the law.

The study found that evasion disguise is much more effective than impersonation disguise.

Citation: Eilidh Noyes, Rob Jenkins. Deliberate disguise in face identification.. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 2019; DOI: 10.1037/xap0000213

Comments