In the July 24th

New York Times, there is a

featured article about a new, thorny issue—what to do about the millions of Americans who are infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV).

This article is a perfect example of the law of unintended consequences. Until recently, there was exactly one treatment for hepatitis C infection, and it was terrible: Interferon (IFN), an immune booster and ribavirin (RBV), a non-specific antiviral which operates by an unknown mechanism. The IFN-RBV therapy is deeply flawed for two main reasons.

First, it is not very effective. The cure rate ranges from terrible—as low as 20 percent for one of the strains of genotype 1, to mediocre (cure rates that are typically in the 40-70 percent range for other strains). Worse still is that genotype 1 is not only the toughest virus to cure, but also the most prevalent, and by far.

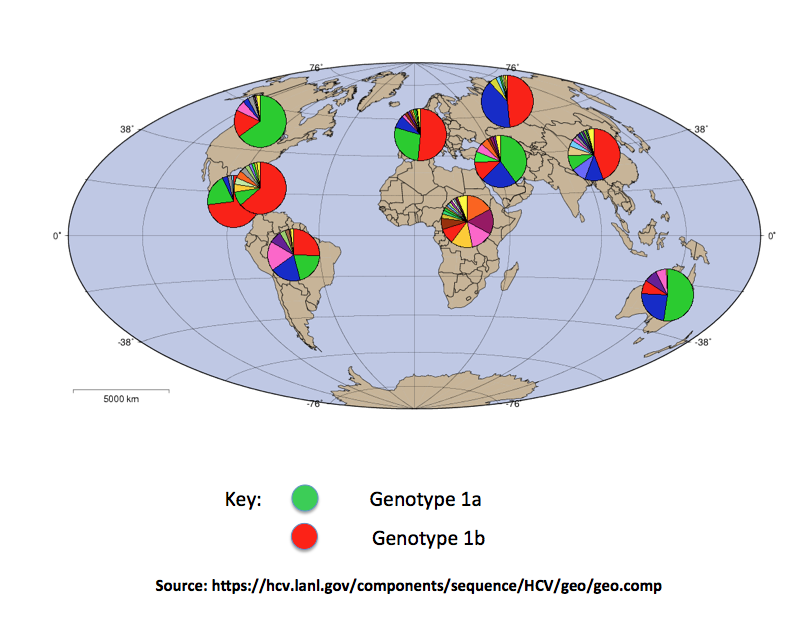

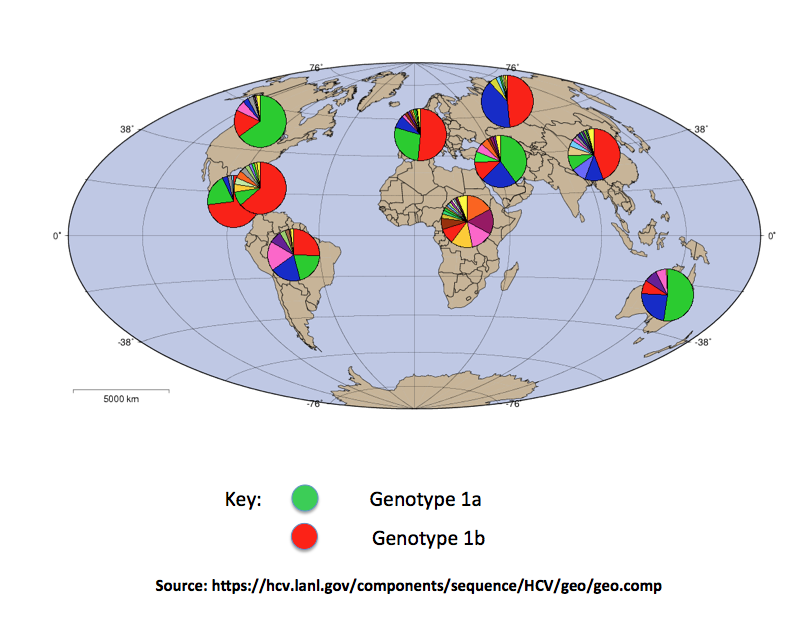

HCV genotype 1 is responsible for more than 70 percent of all infections worldwide. This is especially

bad, since Genotype 1b (red in graphic below) is the worst of the worst. This is the strain with a 20 percent cure rate.

In case this isn't bad enough, a look at the

side effects from IFN/RBV is like something from a horror movie:

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Anorexia

- Diarrhea

- Insomnia

- Irritability

- Depression (and this can be very serious, including suicidal ideation)

- Alopecia (hair loss)

- Skin Rash

- Anemia

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelet count)

- Shortness of Breath

- Chest pain

- Visual Changes

- Thyroid Dysfunction

Aside from all of this, it's perfectly fine.

All of this changed in 2013 when Gilead received FDA approval for Sovaldi—the first effective specific antiviral drug against HCV. Not only did Sovaldi (and it's newer and even more effective cousin (Harvoni—a combination of Sovaldi with another Gilead drug), work beyond expectations (cure rates are approaching 100 percent), but there is quite a difference in safety:

"The most common side effects reported with this drug were fatigue and headache. When this drug was studied with ribavirin, the most common side effects to this combination were consistent with known ribavirin side effects; frequency and severity of the expected side effects were not increased. Therapy was permanently discontinued due to side effects in 0%, less than 1%, and 1% of patients using this drug for 8, 12, and 24 weeks, respectively, and less than 1%, 0%, and 2% for patients using this drug with ribavirin for 8, 12, and 24 weeks, respectively."

OK, so there is now a treatment for hepatitis C that is nothing short of miraculous. What could go wrong? The answer: plenty.

First and foremost is economic. Sovaldi costs $1,000 per pill—$84,000 for the 12 week treatment. Harvoni costs about $100,000. (These numbers are no longer accurate, since Gilead plans to discount Sovaldi by 46 percent.) Even with the discount, $40,000 for a full course of Sovaldi is pricey (although very cost-effective)

Ironically, the "problem" arises from the remarkable efficacy of these new medicines. Since they work so well, everyone wants them. However, given the large number of Americans who are infected—3.2 million—and the price, hepatitis C treatment is putting a strain on budgets of a number of providers, such as Medicaid, the Veteran's Administration, and insurance companies.

However, cost is only one facet of this dilemma. Other factors are more nuanced, but just as important: Should everyone who is infected with HCV have access to these drugs. Medically, of course, but in the real world, this is not so clear.

This may sound harsh and possibly even judgemental, but I believe that there are valid arguments why many HCV-infected patients should not automatically have access to these drugs.

- Hepatitis C is a very unusual infection. Signs of liver damage are typically seen as much as two or three decades following infection. During this time, even though people are infected, there will be no symptoms until the liver is sufficiently damaged. Although in a perfect world, people who are infected would get treatment right away, the downside of waiting for even 10 years—at which time these drugs will be much less expensive—is not awful.

- A little more incendiary: Should a 25-year old heroin addict, who became infected from needle sharing, receive a $100,000 treatment, given the likelihood that he or she will like still be addicted after they are cured, only to become reinfected in the way that they became infected in the first place?

- This dilemma is not new, nor is it strictly a medical issue. It is perhaps, even more so, about medical ethics rather than medicine. Should alcoholics receive new livers if they continue to drink following the transplant? Most, but not all medical ethicists believe that a 6-month abstinence interval prior to transplant should be required. The parallel to HCV treatment dilemma is obvious.

Comments