When I first saw a new article about cow tipping, I bristled just a little. The last thing American culture needs is another flatlander telling real farmers whether or not cows fall over. But Jake Swearingen, Digital director at Modern Farmer, does a good job dealing with a sensitive topic. Sensitive may be the wrong word. Cow tipping brings out the passion in cows.

And people too. You think the neo-cons in the White House and peaceniks in the public are going at each other over Syria? Tell someone in the city a hillbilly can't tip a cow. Everyone knows of someone who did it. Heck, I do too.

I've just never seen someone do it.

And I sure never tried. Cows are heavy and as a teenager who weighed 160 pounds, moving an animal that size without a rope around its horns and a tractor was an udder impossibility. Okay, I mixed genders to make that joke - but we only had steers, no dairy cows. Though everyone claims to know someone who tipped a cow, I think I only saw it tried in "Tommy Boy". It's true urban legend, because only flatlanders in the city believe it.

Cow tipping has been dealt with before - Straight Dope debunked it way back in 1990 (Harvard Crimson too) and those are the earliest I know of, it may go back farther than that. Heck, I wrote an article on caber-tossing and nowhere near as many people claim they know someone who tossed a caber, so lots of articles have probably been written on cow tipping. Well, they have, sure, but science media needs stuff to write about today, and Swearingen gave them (errr, us, I supposed) that. More on that in the note (1).

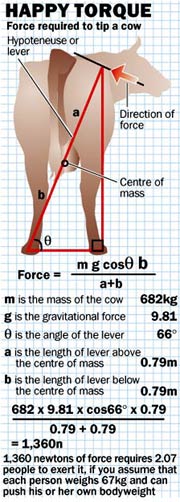

In 2005, two researchers claimed that one person could not tip a cow - since it was Canada, they used those French numbers and said that a cow of 1.45 metres in height, pushed at a tipping angle of 23.4 degrees, would require 4.43 people to push 1400-1600 lbs. over - and that is only if you are lucky enough that the cow stays still. Somewhere the rumor got started that cows sleep standing up, which means someone might think they are able to sneak a push in. It's untrue, even if you are drunk and almost anything is possible.

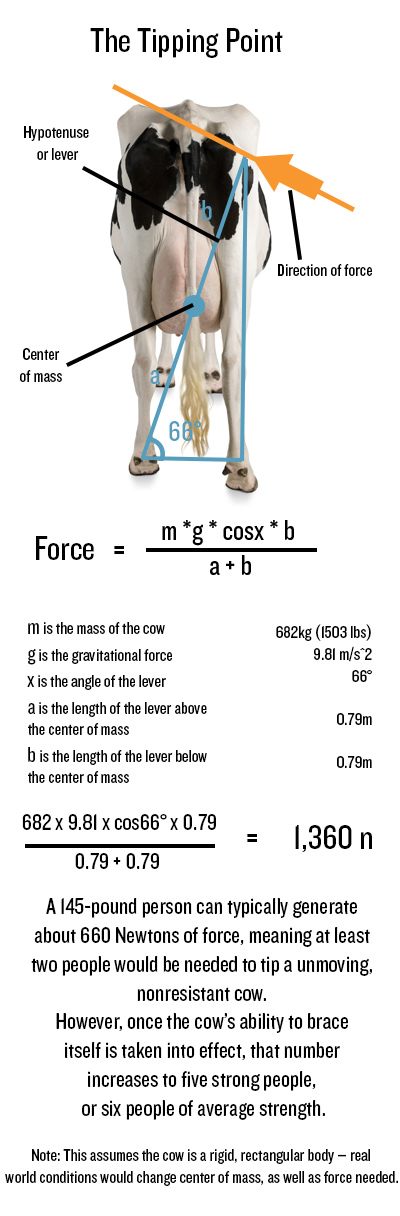

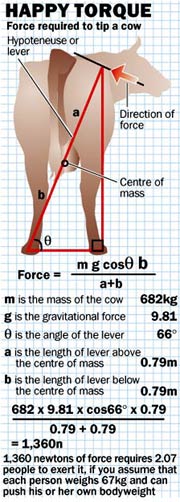

Diagram adapted from Popular Mechanics, using the work of Dr. Margo Lillie and Tracy Boecher. Credit and link: Modern Farmer.

Diagram adapted from Popular Mechanics, using the work of Dr. Margo Lillie and Tracy Boecher. Credit and link: Modern Farmer.

Swearingen makes the point in the bessy way possible (2); if cow tipping were possible, some idiot would be doing it on YouTube. In reality, you'd have better luck standing in a muddy field full of cow dung and tipping over a Volkswagen. At least the Volkswagen wouldn't move.

So why does the myth stick around? Swearingen wonders as well and asks California State University Northridge anthropologist Professor Sabina Magliocco, who has covered similar weighty topics, such as witchcraft and paganism and even created folklore about her cats.

Magliocco says legends stick around for the same reason jokes do; “You’re putting the world — or in this case a cow — on its side.” And city folk are more inclined to believe it because they think the country is boring without all the crime and pollution.

Actually we can use "Tommy Boy" again to show symbolic inversion. When Chris Farley's character pleads with the workers at the family business to pitch in and help him save the company, his appeal goes:

"Ever since i was a kid, you people have been like a family to me.

"Louis, we built our first fort together.

"And Danny, remember when we used to burn ants with a magnifying glass?

"R.T., i lost my virginity to your daughter, for crying out loud! Rob, you were there."

He used warm nostalgia to reveal to a father his daughter is a tramp? Classic comedy - and symbolic inversion. The cow tipping scene in that movie is far less funny.

Swearingen also postulates that such comedy scenes in movies may be why it sticks around and points to a nexus around the same period - like science media, Hollywood screenwriters tend to copy each other. He may have a point. I didn't ask about cow tipping when I was a young guy living in the country - we all knew better - but I imagine if I had asked, an old farmer would have looked at me like I asked if I could fly the cow to Cuba. Today, even some rural people claim it can be done, so they are being educated by media and not physics.

Luckily for modern youth, they have the Internet to learn these lessons. But I bet it won't prevent some hapless kid from getting duped into trying it.

NOTES:

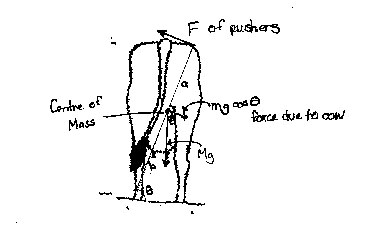

(1) Where was this work published? See if you can find out without me telling you. I am working on an article regarding peer review of science media and this might be a good example; Swearingen links to a blurb on the University of British Columbia website about media coverage of the research, and never mentions a paper. He says his graphic came from Popular Mechanics but I couldn't find their article (I will keep looking before I included anything about this in my piece on peer review of science media) but I imagine Swearingen's graphic is better. Here is an original graphic from the author:

And then one other I found from 2005:

Wikipedia's source is a newspaper piece that discussed it but that is an inactive link. Wayback Machine has it. But we expect nothing from Wikipedia anyway. In 2005, a whole daisy chain of science media gushing occurred and this past week, it happened again. Swearingen wrote about it and then everyone jumped on it. Obviously I am doing the same thing, his piece reminded me again that myths of how physics trump biology are pernicious - but it may be that this is an example of a larger issue.

The only publication that mentioned a source? Maggie Wittlin at the now defunct Seed Magazine, who says Boecher wrote it for a class in zoological physics and Lillie fixed some of the math.

(2) I love slipping those in.

And people too. You think the neo-cons in the White House and peaceniks in the public are going at each other over Syria? Tell someone in the city a hillbilly can't tip a cow. Everyone knows of someone who did it. Heck, I do too.

I've just never seen someone do it.

And I sure never tried. Cows are heavy and as a teenager who weighed 160 pounds, moving an animal that size without a rope around its horns and a tractor was an udder impossibility. Okay, I mixed genders to make that joke - but we only had steers, no dairy cows. Though everyone claims to know someone who tipped a cow, I think I only saw it tried in "Tommy Boy". It's true urban legend, because only flatlanders in the city believe it.

Cow tipping has been dealt with before - Straight Dope debunked it way back in 1990 (Harvard Crimson too) and those are the earliest I know of, it may go back farther than that. Heck, I wrote an article on caber-tossing and nowhere near as many people claim they know someone who tossed a caber, so lots of articles have probably been written on cow tipping. Well, they have, sure, but science media needs stuff to write about today, and Swearingen gave them (errr, us, I supposed) that. More on that in the note (1).

In 2005, two researchers claimed that one person could not tip a cow - since it was Canada, they used those French numbers and said that a cow of 1.45 metres in height, pushed at a tipping angle of 23.4 degrees, would require 4.43 people to push 1400-1600 lbs. over - and that is only if you are lucky enough that the cow stays still. Somewhere the rumor got started that cows sleep standing up, which means someone might think they are able to sneak a push in. It's untrue, even if you are drunk and almost anything is possible.

Diagram adapted from Popular Mechanics, using the work of Dr. Margo Lillie and Tracy Boecher. Credit and link: Modern Farmer.

Diagram adapted from Popular Mechanics, using the work of Dr. Margo Lillie and Tracy Boecher. Credit and link: Modern Farmer.Swearingen makes the point in the bessy way possible (2); if cow tipping were possible, some idiot would be doing it on YouTube. In reality, you'd have better luck standing in a muddy field full of cow dung and tipping over a Volkswagen. At least the Volkswagen wouldn't move.

So why does the myth stick around? Swearingen wonders as well and asks California State University Northridge anthropologist Professor Sabina Magliocco, who has covered similar weighty topics, such as witchcraft and paganism and even created folklore about her cats.

Magliocco says legends stick around for the same reason jokes do; “You’re putting the world — or in this case a cow — on its side.” And city folk are more inclined to believe it because they think the country is boring without all the crime and pollution.

Actually we can use "Tommy Boy" again to show symbolic inversion. When Chris Farley's character pleads with the workers at the family business to pitch in and help him save the company, his appeal goes:

"Ever since i was a kid, you people have been like a family to me.

"Louis, we built our first fort together.

"And Danny, remember when we used to burn ants with a magnifying glass?

"R.T., i lost my virginity to your daughter, for crying out loud! Rob, you were there."

He used warm nostalgia to reveal to a father his daughter is a tramp? Classic comedy - and symbolic inversion. The cow tipping scene in that movie is far less funny.

Swearingen also postulates that such comedy scenes in movies may be why it sticks around and points to a nexus around the same period - like science media, Hollywood screenwriters tend to copy each other. He may have a point. I didn't ask about cow tipping when I was a young guy living in the country - we all knew better - but I imagine if I had asked, an old farmer would have looked at me like I asked if I could fly the cow to Cuba. Today, even some rural people claim it can be done, so they are being educated by media and not physics.

Luckily for modern youth, they have the Internet to learn these lessons. But I bet it won't prevent some hapless kid from getting duped into trying it.

NOTES:

(1) Where was this work published? See if you can find out without me telling you. I am working on an article regarding peer review of science media and this might be a good example; Swearingen links to a blurb on the University of British Columbia website about media coverage of the research, and never mentions a paper. He says his graphic came from Popular Mechanics but I couldn't find their article (I will keep looking before I included anything about this in my piece on peer review of science media) but I imagine Swearingen's graphic is better. Here is an original graphic from the author:

And then one other I found from 2005:

Wikipedia's source is a newspaper piece that discussed it but that is an inactive link. Wayback Machine has it. But we expect nothing from Wikipedia anyway. In 2005, a whole daisy chain of science media gushing occurred and this past week, it happened again. Swearingen wrote about it and then everyone jumped on it. Obviously I am doing the same thing, his piece reminded me again that myths of how physics trump biology are pernicious - but it may be that this is an example of a larger issue.

The only publication that mentioned a source? Maggie Wittlin at the now defunct Seed Magazine, who says Boecher wrote it for a class in zoological physics and Lillie fixed some of the math.

(2) I love slipping those in.

Comments