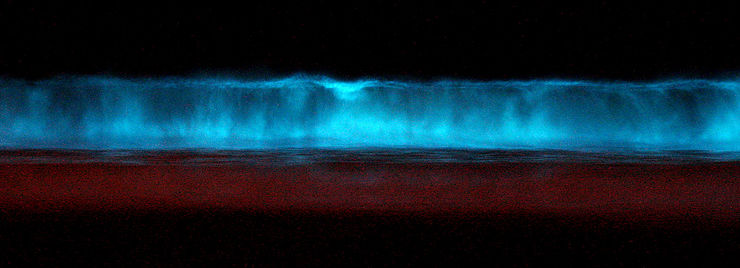

A group of Swedish, American, and Israeli scientists (gotta love that multicultural research!) suggests that big squid need big eyes to see their big predators--sperm whales. Specifically, big eyes are great for spotting the luminous clouds kicked up by sperm whales as they jostle the bioluminescent plankton of the deep.

If this sounds familiar, it's because the story went viral in the media--from NPR and the BBC to National Geographic and Wired, just to name a few. It's been blogged by heavyweights like Ed Yong. At first, I was hesitant to jump into the fray. What could I possibly add?

I could point out the shakiest part of the argument--except the authors helpfully did that already:

The only variable likely to be critically different to our assumption is the density of bioluminescent organisms, and in areas with only little bioluminescence, the advantage of giant eyes would be diminished.The enormous eyes of giant and colossal (can I use the portmanteau gilossal?) squid are only useful if the deep sea is absolutely lousy with bioluminescent plankton. Otherwise, sperm whales won't make much of a cloud and gilossal squid won't be able to see them. Problem is, no one knows just how much plankton-shine the deep sea holds.

For the squid, it would be like seeing a pretty wave--shaped like a deadly predator. (NWE)

Even if there are enough plankton for the trick to work, though, the authors point out that the sperm whale will "see" the squid (using sonar) before the squid can see the sperm whale. Wouldn't it be more useful, then, for the squid to be able to detect sonar? But Nilsson et al. contend that "squid are deaf to the high-frequency sonar clicks of toothed whales." Say what?

Their claim is based on two studies with longfin inshore squid, a different species from an entirely different suborder than gilossal squid. Personally, I'm not convinced the results are applicable. But I fully recognize the difficulty of performing laboratory studies on the largest squid in the world; it may be a long time before we can know for certain.

Nilsson et al. go on to point out that big eyes require a big body to build and sustain them. That big body may also be useful for executing escape maneuvers in the short period of time between seeing the whale and being attacked by the whale.

It is thus possible that predation by large toothed whales has generated a combined selection driving the evolution of gigantism in both bodies and eyes of these squid.But wait. Gilossal squid aren't the only squid that sperm whales eat, are they? No indeed they are not. Hmm, let me see, what other species of squid do sperm whales eat . . .

Of course, Humboldt squid! In the eastern Pacific where they are available, Humboldt squid are a favorite food of sperm whales. And yet Humboldt squid, while quite large, are certainly not "giant" or "colossal", and neither are their eyes. One has to wonder: why not?

Humboldt squid eyes: big but not gilossal.

I see three possible answers:

1) Nilsson et al. are wrong. Sperm whale predation isn't the reason that gilossal squid got so big and grew such big eyes. (This answer does not satisfy me, because the paper really is quite compelling.)

2) Humboldt squid are actually on the same evolutionary trajectory as gilossal squid, but lagging behind. In a few tens of thousands of years, Humboldts will be huge. (Also annoying. Based on what little we know, Humboldts probably have a shorter lifespan than giants or colossals, so if anything you'd expect them to evolve more quickly.)

3) Humboldt squid have an additional constraint, not possessed by either giant or colossal squid, which prevents them from getting too big and growing big eyes.

I'm quite taken with #3. After all, Humboldt squid lead a very different lifestyle. As far as we know, giants and colossals live in the deep sea all the time, but Humboldts make vertical migrations, zooming every day between the deep and the surface--and they may make long-distance horizontal migrations as well. Basically, Humboldt squid are endurance athletes.

Maybe it's good to be big for short-term evasive sprints, but when it comes to the daily grind of migration, it's a bad plan. For one of my thesis chapters, I built a mathematical model of squid swimming, and I found a "sweet spot" where squid are neither too small nor too large to be both fast and efficient. (This is like a teaser! Hopefully the paper will be published soon, and you can be all, oh yeah, I knew about that.) Anyway, perhaps Humboldt squid have evolved to take advantage of that sweet spot, thereby sacrificing the possibility of growing freakishly large.

This idea becomes especially compelling if you believe February's big squid news: that flying out of the water is a regular and important tactic for Humboldt squid and their fellow mid-size ommastrephids.

No way could a gilossal squid pull this off. (photo credit: Bob Hulse)

Comments