The Vikings did not use charts and instruments to navigate the open seas. Having developed skills in coastal navigation they extended those skills to pelagic navigation, or 'island-hopping'. Using the sun as a reference to determine where south lies, the Vikings could sail a reasonably accurate course. If the wind was steady, the wind itself could be used as an aid to direction if the sun was hidden by heavy cloud. It was only when wind and sun both failed the navigator that he was likely to miss his mark.

A Viking ship sailing on a beam reach.

Screenshot from The Vikings, 1958.

Island-hopping should not be taken as implying any need to stop over at an island or even to go ashore. Inhabited, uninhabited or uninhabitable - islands are useful as waypoints. A Viking wanting to sail directly to a far distant destination had not the means to navigate accurately enough to ensure landfall at the desired place. An indirect route via waypoints is longer and requires more provisions for the journey. The great advantage of using waypoints is that each waypoint presents a new point of departure that is accurately known.

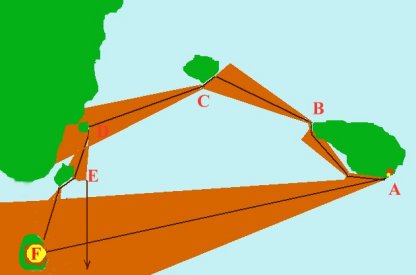

During a sailing voyage navigated only by sun and wind the margin of error would be quite large. Errors of navigation can accumulate to such an amount that a target island or landfall is missed entirely, even if using a sextant and compass. As the image below shows, an attempt to sail directly from A to F could lead to the navigator missing the destination entirely through errors of navigation. By sailing in legs A-B, B-C etc., each departure from a waypoint effectively resets the errors to zero. A Viking sailor using waypoints could be far more confident of reaching his desired destination than if he tried to make the voyage in a single leg.

Island-hopping.

Hvitsark

Hvitsark was the most famous waypoint used by Viking navigators between Iceland and Greenland. It is very easy to locate Hvitsark from the references in the Viking sagas. Unfortunately, from about 1300 onwards there was some confusion amongst scholars outside of Iceland as to what Hvitsark was and where it was. That confusion continues to this day.

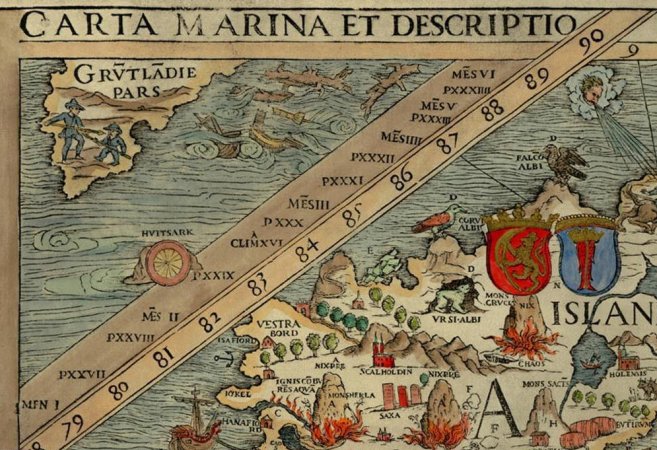

The confusion began with the somewhat dubious accounts of the voyages of the Zeno_brothers and the exploits of Pining and Pothorst. The misapplication of the name Hvitsark to a seamark supposedly erected by Pining and Pothorst has, I suggest - added to the myth and mystery of Hvitsark. The Carta Marina of Olaus Magnus shows Hvitsark as an island somewhere off the coast of Greenland. A part of Greenland and Hvitsark are placed in an inset. If the inset is not understood as such, Hvitsark appears to lie about midway between Iceland and Greenland.

Carta Marina, detail showing Hvitsark.

Olaus Magnus, 1539

From Iceland to Greenland

A Viking named Gunnbjörn Son of Ulf the Crow, intending to sail from Norway to Iceland, completely missed Iceland and accidentally discovered some rocky islands. These islands became known as Gunnbjörn's Skerries. He also noticed a prominent feature which was later named Hvitsark. That landmark is called by three different names in various sagas: hvitsark, blasark or midjokul.

A web search shows that many writers take Hvitserk to be 'white shirt' - a mountain which was at one time snow-capped. One theory has it that the snow cap melted and the mountain became know as blasark - meaning black shirt. Unfortunately for that theory, blaserk does not mean black shirt. Because Hvitsark has been supposed by some people to be a mountain visible at the same time as Snæfellsjökull from some point in the sea, Greenland's highest mountain - Gunnbjørn Fjeld - has been taken to be Hvitsark.

In the saga of Eric the Red, Hvitsark is stated quite clearly to be a glacier. It is called Blaserk. Blaserk - or Blasark - means blue shirt, not black shirt. A glacier can appear white if snow covered or blue if the snow has melted. This has nothing to do with climate change or medieval warm or cold periods. In the summer, the snow on the lower slopes of Greenland's glaciers melts, revealing the ice. The description of this glacier as Blasark or Hvitsark depends only on the time of year in which it is seen.

Where is Hvitsark?

According to the Viking sagas, Hvitsark lies near Gunnbjörn's Skerries, midway between Iceland and Greenland. This has been the cause of much speculation. We know of a certainty that there are no islands midway between Iceland and Greenland. Did these islands sink? Hardly! All that has changed is the application of the term 'Greenland'. In our use of the name Greenland, we need to think like Vikings.

To a Viking, 'Greenland' was a small portion of coast with the east and west settlements. Let us call it Lesser Greenland. To us, 'Greenland' is a vast island. Let us call it Greater Greenland. To us, 'midway between Iceland and (Greater) Greenland' is a point in an empty sea. To a Viking, 'midway' is a term of art of navigation: a point in time marking the completion of half of a journey. To a Viking, 'midway between Iceland and (Lesser) Greenland' is a waypoint used by pelagic navigators.

The Viking navigation directions are perfectly clear and simple. To get to Lesser Greenland, sail due west from Iceland until you come to Gunnbjörn's Skerries and the glacier Hvitsark. Now follow the coast south, sail round the cape and you will soon find the settlements.

The first waypoint in such a journey - the point of departure - is Snæfellsjökull. Due west of Snaefellsjökull, just off the coast of Greenland lie a number of rocky islands. It is virtually certain that these are Gunnbjörn's Skerries.

Supporting evidence

Wilhelm August Graah (1793-1863), in his 1837 book Narrative of an Expedition to the East Coast of Greenland, describes arriving in the vicinity of Kiöge Bay. He speculates that the islands in the area could be Gunnbjörn's Skerries. In a footnote on page 100 he cites Ivar Bardson, who sailed to Greenland circa 1341 - 1347:

From Snefjeldnaes (situated on the) west (coast) of Iceland, the distance to Greenland is shortest, ... then lie Gunnbjörn's Skerries exactly half-way between Greenland and Iceland, ...Graah suggests that the islands he identifies as Gunnbjörn's Skerries would be four days sailing from Iceland for a Viking ship. That would suggest an average speed of about 5 knots sustained over 4 x 24 hours - quite within the capabilities of Viking seagoing ships, one may think.

In his book Greenland, 1943, Vilhjalmur Stefansson translates the Saga of Eric the Red from the Icelandic of the Reykjavic 1935 edition:

Erik now stood out to sea abreast of Snaefellsjökul. He reached land opposite that glacier (in Greenland) which is named Blaserk (Blue Sark). He followed the land south ...

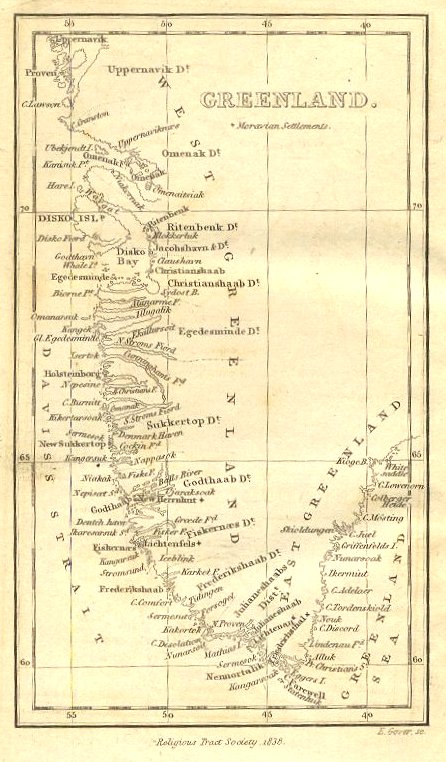

A map of Greenland from Missionary Records. Northern Countries. The Religious Tract Society, 1839, shows a feature named White Saddle near Kiöge Bay. I suggest that a glacier with two prominent 'arms' might appear to be shirt-shaped to one person, but saddle-shaped to another.

Greenland 1838, showing White Saddle at 65o on the east coast.

Discussion:

Is the evidence here presented sufficient to establish to a sufficient degree of certainty that Hvitsark is a glacier and that Hvitsark and Gunnbjörn's Skerries are located on the east coast of Greenland at the same latitude as Snæfellsjökull ?

Which glacial feature, if any, in the vicinity of Kiöge Bay best resembles a generic shirt or saddle?

Does the suggestion that Hvitsark became known as Blasark when the snowcap of one of Greenland's mountains melted due to the medieval warming of Greenland's climate have any scientific merit ?

Comments