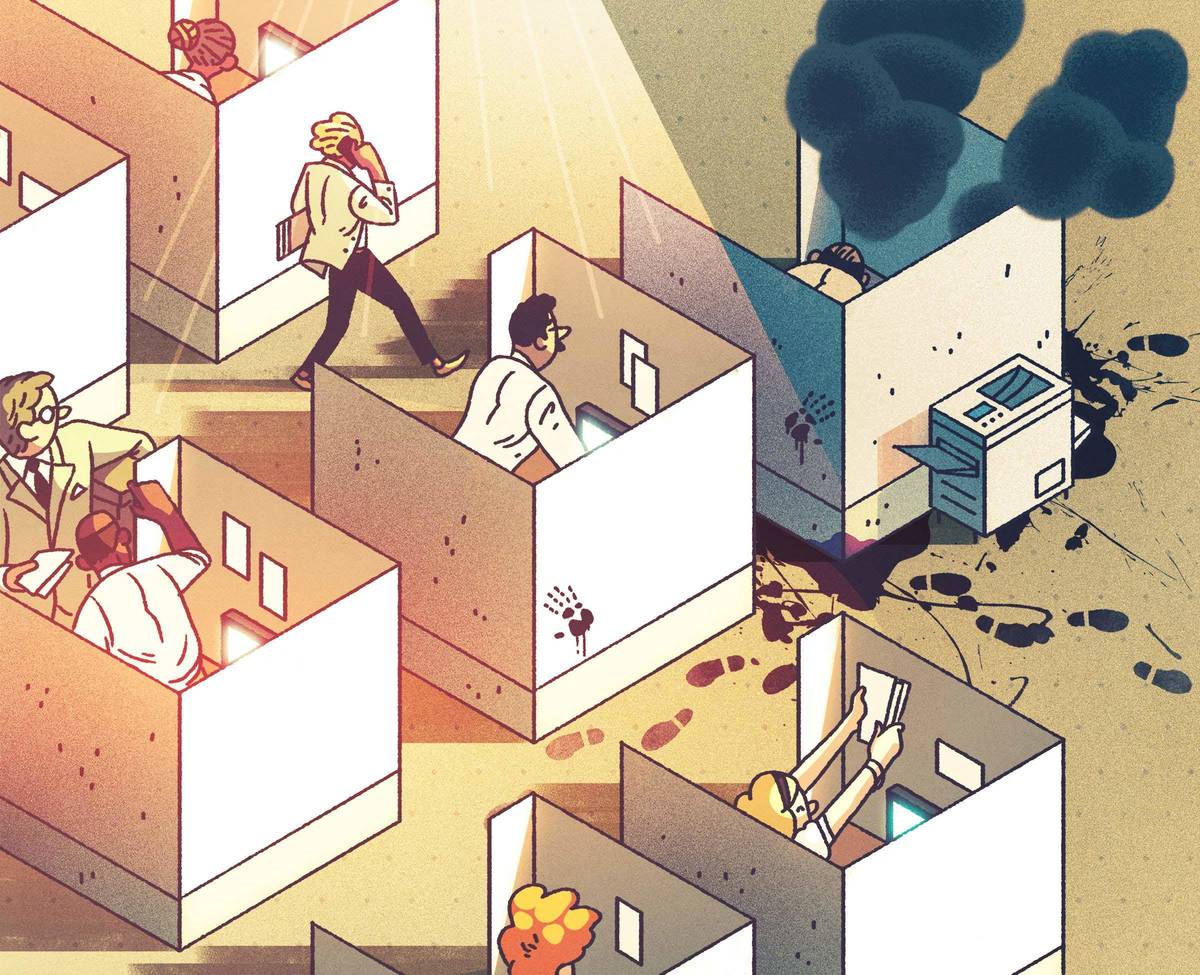

Poor workers impacted their neighbors also, and even more. While “positive spillover” translated into an estimated $1 million in additional annual profits, "negative spillover" from so-called toxic workers was even more pronounced—sometimes having twice the magnitude of impact on profits as positive spillover.

And toxic spillover happens fast. The good news for your team as that its effect dissipates almost immediately once that worker is either fired or relegated to the far physical reaches of the company.

That means companies potentially have a very cheap way to boost productivity—simply shift some desks around—as opposed to relying on expensive lawsuits if a bad employee is fired, and then even more for training and recruiting. In an era where companies are experimenting with open floor plans and other nontraditional seating arrangements, the stakes can be high.

Spatial management really does matter

Using data from consulting firm Cornerstone OnDemand, in 2017 the scholars analyzed more than 58,000 hourly service workers at 11 well-known firms. They found that a toxic worker’s negative financial impact—$12,800 by their calculation—was far greater than the financial boost that comes from a superstar.

Using data from consulting firm Cornerstone OnDemand, the scholars analyzed more than 58,000 hourly service workers at 11 well-known firms. They found that a toxic worker’s negative financial impact—$12,800 by their calculation—was far greater than the financial boost that comes from a superstar.

One company involved wanted them to drill down more. You've known since kindergarten that who you sit next to can matter but they wanted empirical data on how physical proximity impacted the workplace, especially in an era of open floor plans.

The challenge: People are not uniformly good or bad at their jobs; many excel in some areas and are average or below average in others. No one today is just putting widgets together one piece at a time.

So what did physical proximity do when employees’ work was approached in a multidimensional way? Michael Housman and Dylan Minor got two years’ worth of detailed information on the performance of more than 2,000 workers at the tech firm. They picked two measures of performance—speed and quality—and gave workers a ranking of either high or low for each.

They defined toxic workers as anyone whose behavior was so bad that they were fired. Toxic workers ended up comprising about 2 percent of the workers studied.

Then the researchers literally mapped out where each employee sat and analyzed how each person’s work shifted over time as their neighbors changed.

Employees who ranked high on either speed or quality boosted the performance of those within a 25-foot radius. The impact was particularly strong on those who were matched with someone who had a complementary skill. In other words, if Janet is rated high for speed and Mark is rated low, Mark’s speed will improve when he sits near Janet, more so than if they were both already speedy workers. The same holds true for quality.

And, crucially, Janet’s speed will not be dragged down by the slower-moving neighbor.

Toxic workers are really, really toxic. And they infect their neighbors very quickly.

The researchers defined toxic narrowly, as someone fired for their behavior. This means that simply sitting near someone who gets fired means you yourself are now more likely to commit an act heinous enough to merit firing.

“Once a toxic person shows up next to you, your risk of becoming toxic yourself has gone up,” Minor says. And while positive spillover was limited to about a 25-foot radius, with toxic workers, “you can see their imprint and negative effect across an entire floor.”

This toxic spillover happens almost immediately. The researchers saw neighbors go bad, so to speak, as soon as that toxic neighbor showed up. Whereas positive spillover that boosted speed or quality generally took a month to impact a lower-performing neighbor.

Why is negative spillover so much more powerful than positive? Minor believes it is line with many other psychological studies that show that, “negative effects have more of a magnitude than positive effects.” For example, losing $100 is more painful than winning $100 is joyful.

But even among the toxic, there is reason to be reassured, Minor says. “Once they’re transferred or fired, your risk pretty much immediately subsides.” Plus, he adds, “most people are not toxic.”

Learning vs. Peer Pressure

Next the researchers explored why spillover happens. Are people learning good or bad behavior from their neighbors or is something like peer pressure at work?

They reasoned that if employees were learning from those nearby, then the positive or negative effects would continue after their influential neighbor left. But the data showed that both positive and negative spillover were fleeting.

While this is unfortunate for positive spillover—wouldn’t it be great if the improved employee continued being awesome forever?—it is good news in the negative department.

“You could have this other kind of model where people learn how to become a criminal or a jerk and then they stay a criminal or a jerk,” Minor says.

Comments