The 50th anniversary of Alan Shepard's flight, the first American in space, was something of a big deal in pop culture. The 50th anniversary of John Glenn orbiting the Earth, arriving this winter, will likely be a much bigger deal because Sen. Glenn has a lot of name recognition.

But between them in aerospace history, chosen to be among the "Mercury 7" test pilots who were picked when NASA was just six months old and who risked their lives flying into the great unknown, is a guy who doesn't get enough respect.

He's a man who was America's first space program casualty and was perhaps America's unluckiest astronaut - if you can say that about a guy who was a war hero that won the Distinguished Flying Cross and was then a test pilot and then one of few chosen for the boldest adventure in American history. His name was Gus Grissom and he was the second man in space. But few know his name.

I mean, he died for space. Everyone can remember where they were when the Challenger shuttle exploded. How many people can recall what they were doing when they found out Grissom and Ed White and Roger Chaffee died during a pre-launch test for the Apollo 1 launch?

In modern culture, most of what the public knows about Gus Grissom is perhaps a little from Tom Wolfe's book "The Right Stuff"(1979), though more likely the Philip S. Kaufman move of the same name. Both are powerful in their own ways, "The Right Stuff"(1983) is one of the greatest movies of all time, but Grissom gets a rather poor showing.

Wolfe was inspired to write the book after getting an assignment to cover the last Moon mission and became fascinated with the beginning. He clearly loved his subject and, in the book, he covers the bases. Grissom, in Liberty Bell 7, had a hatch explode after re-entry. The capsule was lost. Grissom said he had nothing to do with it and the engineers said it couldn't have happened by accident.

Liberty Bell 7 Explosive Hatch Diagram. From the NASA Mercury Spacecraft Familiarization Manual May 1962

But really, when do engineers ever say they didn't account for every possibility and that it might not instead be human error? Unlike Shepard's, Grissom's spacecraft had a new explosive hatch release to allow him to exit during an emergency and it could also be triggered from outside. His fellow astronauts did not like the assertion it was pilot error and Wally Schirra manually blew his capsule's hatch after recovery to dispel the rumor that Grissom might have blown Liberty Bell 7's hatch on purpose and covered it up. The kickback from the manual trigger left Schirra with an injury to his hand, an injury Grissom did not have during his post-flight physical. Deke Slayton, another Mercury astronaut and then NASA's Director of Flight Crew Operations, certainly could not have thought that Grissom did not have the right stuff or he would not have gotten an assignment on the next program, Gemini, and Apollo after that.

I called John Glenn, former astronaut, war hero and retired Senator, to try and get some insight on what he thought about Grissom in general and if history has treated him fairly. A message from his assistant said she was unable to schedule any interviews for him at the current time. Likewise, a message to the only other Mercury astronaut still living, Cmdr. Scott Carpenter, was returned by his representative with a statement that Carpenter "rarely discusses other Mercury astronauts other than to say they were wonderful colleagues and friends."

So instead I have to rely on the people who worked for him, since they did work for him in the sense that his life was on the line and the personal relationship the engineers had with the astronauts in that smaller, mission-oriented NASA was a big motivator for everyone involved. I spoke with Art Cohen, the lead engineer for IBM I interviewed in 50 Years Of Manned Space Flight - An Interview With A Lead Engineer For The Mercury Program. He knew Grissom well and said Grissom was a hands-on guy, he wanted to know how everything worked and he was intellectually curious even among astronauts who were legendary for being intellectually curious. He described Grissom as a quietly competent, modest man - in a group and a culture known for their modesty. Nothing in life came easy to Gus, Cohen said, and so he worked hard.

A visit by NASA to the IBM Project Mercury team at Goddard Space Flight Center. Art Cohen is 4th from the left, astronaut Gus Grissom is middle front and astronaut Deke Slayton is second from the right. Photo: IBM

Walt Harner was part of the design team that built the Project Mercury Launch Monitor Subsystem so he worked with NASA Space Task Group and various contractors and a lot with the astronauts. He told me the general impression was that Grissom would be among the first astronauts to fly if not the first. He called him a bright man, a hard worker and an exceptional pilot.Everyone who worked with him echoes that sentiment. Grissom worked so closely with the engineers on Gemini they nicknamed it the Gusmobile. He is credited with helping invent the multi-axis translation thruster controller Gemini and Apollo spacecraft used to push in linear directions for rendezvous and docking.

So why does the drama remain about his Mercury flight after all this time? In the modern age, movies become our history and "The Right Stuff" is an exceptional movie, but Tom Wolfe disavowed it because of the changes and William Goldman, who has written too many great movies to count (I will list only two - "The Princess Bride" and "Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid" - for brevity) also walked away because of differences with Kaufman.

Kaufman certainly had to have known Grissom perished in the Apollo 1 fire because there was no explosive hatch on the Block 1 Apollo Command Module. Was that a design choice because of persistent belief that the explosion in the hatch on Grissom's Liberty Bell 7 had been self-initiated, as some imply? We have no way to know, we just know he died and he had no chance to prove he didn't "screw the pooch". The media at the time certainly portrayed him that way, even as NASA cleared him, and while Wolfe's book is not as clear in its disdain for his demeanor as Kaufman's movie, it still uses the term 'screw the pooch' - pilot jargon for panic - in relation to him, but it does so by putting it in the mouths of test pilots.

The press of the day criticized Grissom for not having the rigid, by-the-book style of some of the other astronauts. This is a guy who ate a corned-beef sandwich on board Gemini 3. Given what we know about NASA's bloated bureaucratic monolith today, what kind of person do you think NASA needs now more than ever? A Gus Grissom, that's who, a guy who understood acceptable risk and pursued the challenges of the unknown anyway.

After World War II, Grissom worked his way through college as a cook while his wife lived with her parents and took a job. A hard way to be married. He re-enlisted during the Korean War, and then became an astronaut, and when he died had almost 5,000 hours of flying time. It's true, nothing did come easy for him, and he was certainly America's unluckiest astronaut given Mercury and Apollo, but it was just that - bad luck. In his book "Deke!", Deke Slayton said he wanted one of the Mercury Seven to take that first step on the moon and, "Had Gus been alive, as a Mercury astronaut he would have taken the step."

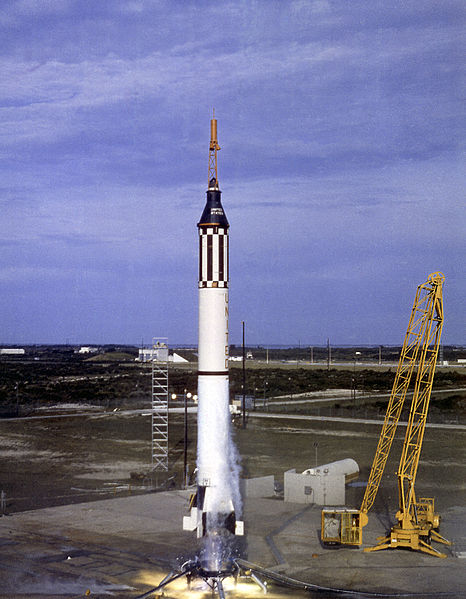

Definitely the right stuff. MR-4 and Liberty Bell 7, 50 years ago today. Thank you for your service, Col. Grissom. R.I.P.

Liftoff of Mercury-Redstone 4 (MR-4), Liberty Bell 7, on July 21, 1961, the second U.S. manned sub-orbital flight with a duration of 15-1/2 minutes. Source: Marshall Space Flight Center's Marshall Image Exchange

Comments