Recent re-examination of a 100,000 year old early human skull using micro-CT scans has revealed the interior configuration of a temporal bone thought to occur only in Neanderthals.

The fossilized human skull was found during 1970s excavations at the Xujiayao site in China's Nihewan Basin. Since Western Europe and Eastern Asia are a long way apart, "The discovery places into question a whole suite of scenarios of later Pleistocene human population dispersals and interconnections based on tracing isolated anatomical or genetic features in fragmentary fossils," said study co-author Erik Trinkaus, PhD, anthropology professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

It's more compelling evidence for interbreeding and gene transfer between Neanderthals and modern human ancestors, he says.

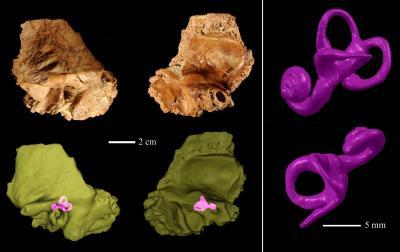

The Xujiayao 15 temporal bone, with the extracted temporal labyrinth and

its position in the temporal bone. Credit: Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Science

"We were completely surprised," Trinkaus said. "We fully expected the scan to reveal a temporal labyrinth that looked much like a modern human one, but what we saw was clearly typical of a Neandertal. This discovery places into question whether this arrangement of the semicircular canals is truly unique to the Neandertals."

Often well-preserved in mammal skull fossils, the semicircular canals are remnants of a fluid-filled sensing system that helps humans maintain balance when they change their spatial orientations, such as when running, bending over or turning the head from side-to-side.

Since the mid-1990s, when early CT-scan research confirmed its existence, the presence of a particular arrangement of the semicircular canals in the temporal labyrinth has been considered enough to securely identify fossilized skull fragments as being from a Neanderthal. This pattern is present in almost all of the known Neanderthal labyrinths. It has been widely used as a marker to set them apart from both earlier and modern humans.

The skull at the center of this study, known as Xujiayao 15, was found along with an assortment of other human teeth and bone fragments, all of which seemed to have characteristics typical of an early non-Neanderthal form of late archaic humans.

Trinkaus has studied Neanderthal and early human fossils from around the globe and said this discovery only adds to the rich confusion of theories that attempt to explain human origins, migrations patterns and possible interbreedings.

The Xujiayao 15 late archaic human temporal bone from northern China, with

the extracted temporal labyrinth, is superimposed on a view of the Xujiayao site. Credit: Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Science

While it's tempting to use the finding of a Neanderthal-shaped labyrinth in an otherwise distinctly "non-Neanderthal" sample as evidence of population contact (gene flow) between central and western Eurasian Neandertals and eastern archaic humans in China, Trinkaus and colleagues argue that broader implications of the Xujiayao discovery remain unclear.

"The study of human evolution has always been messy, and these findings just make it all the messier," Trinkaus said. "It shows that human populations in the real world don't act in nice simple patterns.

"This study shows that you can't rely on one anatomical feature or one piece of DNA as the basis for sweeping assumptions about the migrations of hominid species from one place to another."

Source: Washington University in St. Louis

Comments