A study in mice has found that the space between brain cells may increase during sleep, allowing the brain to flush out toxins that build up during waking hours.

Get a good night's sleep - it may literally clear your mind.

For centuries, scientists and philosophers alike have wondered why people sleep and how it affects the brain. It has been determined that sleep is important for storing memories and the researchers in the new paper found that sleep may be also be the period when the brain cleanses itself of toxic molecules.

Their results show that during sleep a plumbing system called the glymphatic system may open, letting fluid flow rapidly through the brain. Prof. Maiken Nedergaard's lab recently discovered the glymphatic system helps control the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a clear liquid surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

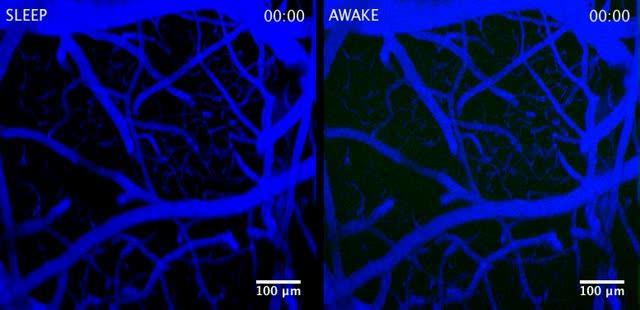

Scientists watched dye flow through the glymphatic system, a brain "plumbing" system, of a mouse when it was asleep (left) and then, later, when it was awake (right). More dye flowed into the brain during sleep. Results from this study suggest the brain may flush out toxic molecules associated with neurodegenerative disorders during sleep.Courtesy of Nedergaard Lab, University of Rochester Medical Center.

Initially the researchers studied the system by injecting dye into the CSF of mice and watching it flow through their brains while simultaneously monitoring electrical brain activity. The dye flowed rapidly when the mice were unconscious, either asleep or anesthetized. In contrast, the dye barely flowed when the same mice were awake.

"We were surprised by how little flow there was into the brain when the mice were awake," said Nedergaard. "It suggested that the space between brain cells changed greatly between conscious and unconscious states."

To test this idea, the researchers used electrodes inserted into the brain to directly measure the space between brain cells. They found that the space inside the brains increased by 60 percent when the mice were asleep or anesthetized.

"These are some dramatic changes in extracellular space," said Charles Nicholson, Ph.D., a professor at New York University's Langone Medical Center and an expert in measuring the dynamics of brain fluid flow and how it influences nerve cell communication.

Certain brain cells, called glia, control flow through the glymphatic system by shrinking or swelling. Noradrenaline is an arousing hormone that is also known to control cell volume. Similar to using anesthesia, treating awake mice with drugs that block noradrenaline induced unconsciousness and increased brain fluid flow and the space between cells, further supporting the link between the glymphatic system and consciousness.

Scientists watched dye flow through the brain of a sleeping mouse. Courtesy of Nedergaard Lab, University of Rochester Medical Center.

Previous studies suggest that toxic molecules involved in neurodegenerative disorders accumulate in the space between brain cells. In this study, the researchers tested whether the glymphatic system controls this by injecting mice with labeled beta-amyloid, a protein associated with Alzheimer's disease, and measuring how long it lasted in their brains when they were asleep or awake. Beta-amyloid disappeared faster in mice brains when the mice were asleep, suggesting sleep normally clears toxic molecules from the brain.

"These results may have broad implications for multiple neurological disorders," said Jim Koenig, Ph.D., a program director at NINDS. "This means the cells regulating the glymphatic system may be new targets for treating a range of disorders."

The results may also highlight the importance of sleep.

"We need sleep. It cleans up the brain," said Dr. Nedergaard.

Citation: Lulu Xie, Hongyi Kang, Qiwu Xu, Michael J. Chen, Yonghong Liao, Meenakshisundaram Thiyagarajan, John O’Donnell, Daniel J. Christensen, Charles Nicholson, Jeffrey J. Iliff, Takahiro Takano, Rashid Deane, and Maiken Nedergaard , 'Sleep Drives Metabolite Clearance from the Adult Brain', Science 18 October 2013: 342 (6156), 373-377 DOI:10.1126/science.1241224

Comments