Researchers have witnessed how football-shaped carbon molecules known as

buckyballs

arrange themselves into ultra-smooth layers, all in real time, and by piecing that together with theoretical simulations, the investigators believe they can advance the field of plastic electronics.

Buckyballs are spherical molecules which consist of 60 carbon atoms (C60), named such because they are reminiscent of American architect Richard Buckminster Fuller's geodesic domes. With their structure of alternating pentagons and hexagons, they also resemble tiny molecular footballs.

Using DESY's X-ray source PETRA III, the researchers observed how buckyballs settle on a substrate from a molecular vapour. In fact, one layer after another, the carbon molecules grow predominantly in islands only one molecule high and barely form tower-like structures. "The first layer is 99% complete before 1% of the second layer is formed," explains DESY researcher Bommel, who is completing his doctorate in Prof. Stefan Kowarik's group at the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. This is how extremely smooth layers form.

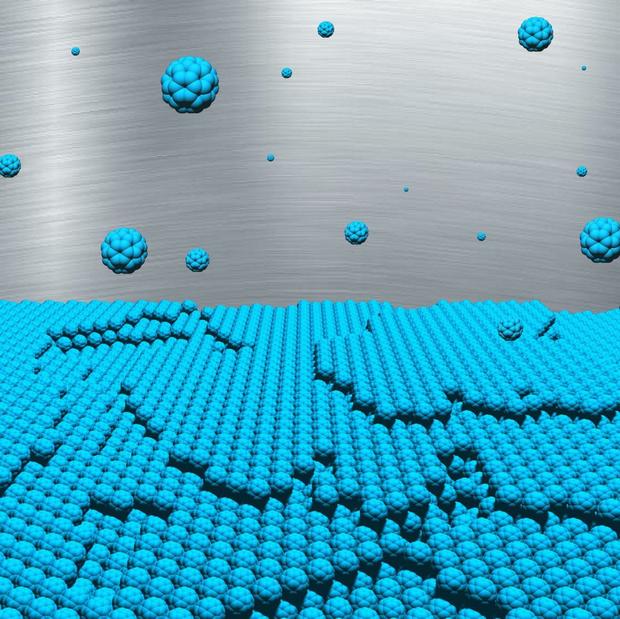

Artistic impression of the multilayer growth of buckyballs. Credit: Nicola Kleppmann/TU Berlin

"To really observe the growth process in real-time, we needed to measure the surfaces on a molecular level faster than a single layer grows, which takes place in about a minute," says co-author Dr. Stephan Roth, head of the P03 measuring station, where the experiments were carried out. "X-ray investigations are well suited, as they can trace the growth process in detail."

"In order to understand the evolution of the surface morphology at the molecular level, we carried out extensive simulations in a non-equilibrium system. These describe the entire growth process of C60 molecules into a lattice structure," explains Kleppmann, PhD student in Prof. Sabine Klapp's group at the Institute of Theoretical Physics, Technische Universität Berlin. "Our results provide fundamental insights into the molecular growth processes of a system that forms an important link between the world of atoms and that of colloids."

Through the combination of experimental observations and theoretical simulations, the scientists determined for the first time three major energy parameters simultaneously for such a system: the binding energy between the football molecules, the so-called "diffusion barrier," which a molecule must overcome if it wants to move on the surface, and the Ehrlich-Schwoebel barrier, which a molecule must overcome if it lands on an island and wants to hop down from that island.

"With these values, we now really understand for the first time how such nanostructures come into existence," stresses Bommel. "Using this knowledge, it is conceivable that these structures can selectively be grown in the future: How must I change my temperature and deposition rate parameters so that an island of a particular size will grow. This could, for example, be interesting for organic solar cells, which contain C60." The researchers intend to explore the growth of other molecular systems in the future using the same methods.

Comments