Human DNA accumulates damage over time and older bodies can't repair it as well as younger, leading to the obvious conclusion that damage builds up over time and leads to an irreversible dormant state known as senescence.

Cellular senescence is believed to be responsible for some of the telltale signs of aging, such as weakened bones, less resilient skin and slow-downs in organ function. DNA damage also seems to play a role in conditions called progerias, which cause premature aging. Progeria patients have mutations in genes responsible for DNA damage repair. Now researchers from the University of Pennsylvania have pinpointed a molecular link between DNA damage, cellular senescence and premature aging.

Finding the key players could lead to therapeutic targets for counteracting some of the negative effects of progerias and perhaps even forestalling the effects of natural aging.

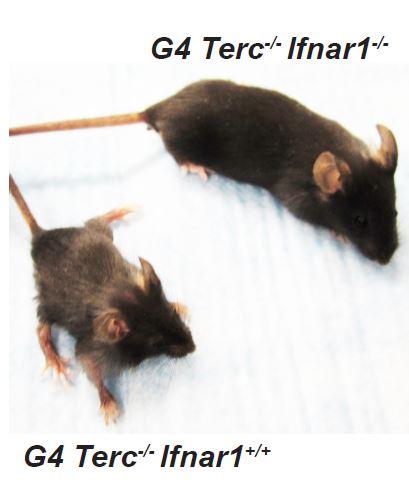

Blocking the interferon pathway in mice with progeria improved their lifespan, body condition and fertility. Credit: University of Pennsylvania

The study, published this week in the journal Cell Reports, took a closer look at the chemical messenger interferon, a molecule that is naturally produced by the body in response to invading pathogens such as viruses. The Penn team found that interferon signaling ramps up in response to double-stranded DNA breaks and that this signaling prompts cells to enter senescence.

When the Penn researchers inactivated the interferon signaling pathways in a mouse model of progeria, however, they were able to extend the animals' lives. These mice were more fertile, had less gray hair and were larger and more robust than animals in which the interferon pathway was still active.

"Our findings imply that some of the effects of DNA damage could be managed by perhaps locally blocking interferon signaling," said Serge Y. Fuchs, senior author on the study and a professor of cell biology in Penn's School of Veterinary Medicine.

Collaborators on the study included Christopher J. Lengner, an assistant professor at Penn Vet, and Roger A. Greenberg and F. Brad Johnson, associate professors at Penn's Perelman School of Medicine. The lead authors were Qiujing Yu and Yuliya V. Katlinskaya of Penn Vet. Additional co-authors on the paper were Penn Vet's Christopher J. Carbone, Bin Zhao, Kanstantsin V. Katlinski, Hui Zheng, Manti Guha and Ning Li and Penn Medicine's Qijun Chen and Ting Yang. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health's National Cancer Institute (CA092900 and CA142425) and an NIH grant (P30-DK050306).

Comments