Most dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago but one dinosaur lineage survived and lives on today – we call these the birds and they rule the skies the way they once ruled land.

An international team, led by scientists from Oxford University and the Royal Ontario Museum, estimated the body mass of 426 dinosaur species based on the thickness of their leg bones. The team found that dinosaurs showed rapid changes in body size shortly after their origins, around 220 million years ago.

However, these soon slowed: only the evolutionary line leading to birds continued to change size at this rate, and did so for a further 170 million years, producing new ecological diversity not seen in other dinosaur lineages.

The study suggests that shrinking their bodies may have helped this group to continue exploiting new ecological niches throughout their evolution, and to become such a diverse and widespread group of animals today.

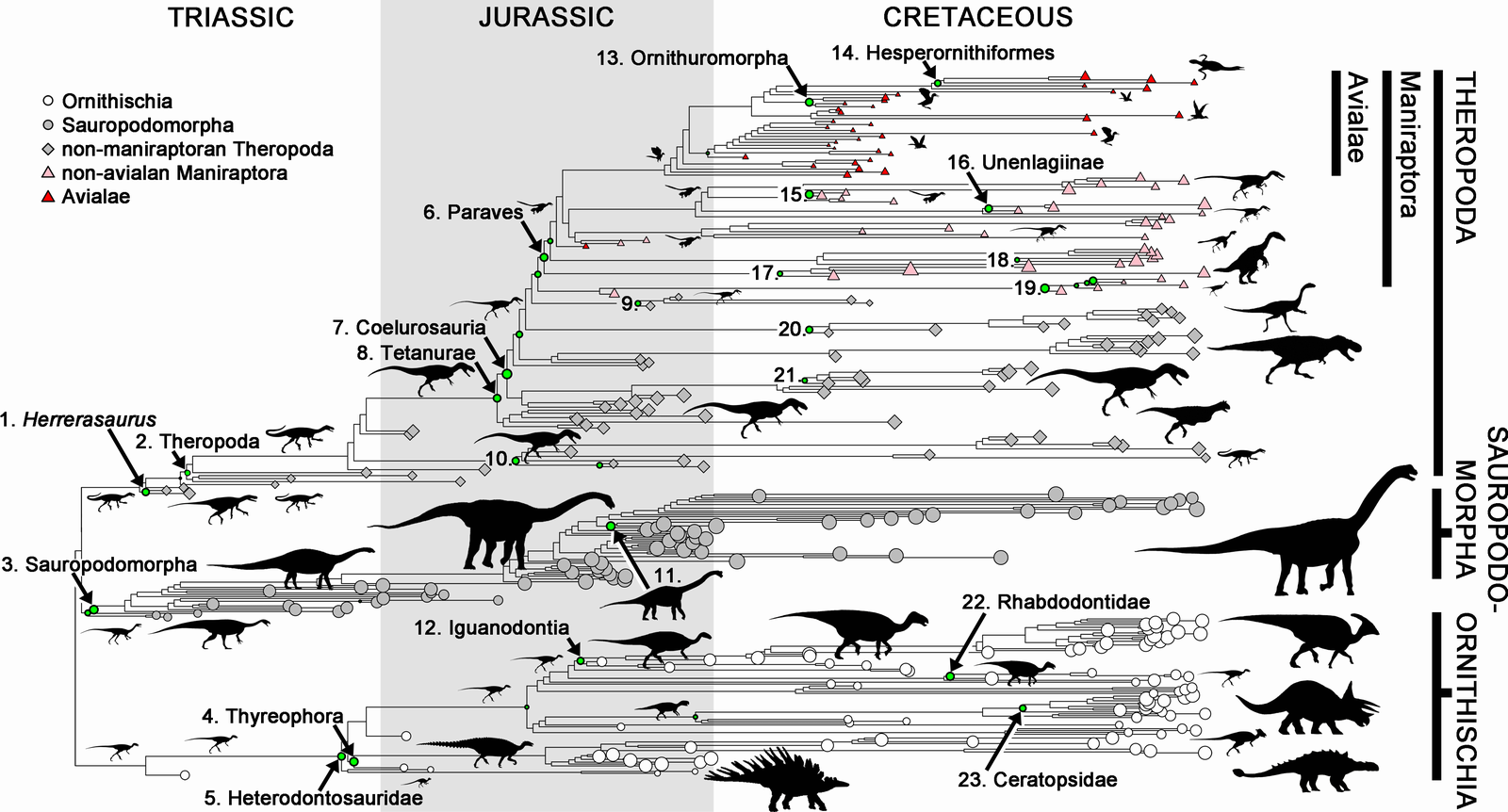

CLICK FOR LARGER SIZE. Dinosaur phylogeny showing nodes with exceptional rates of body size evolution. Exceptional nodes are numbered and indicated by green filled circles with diameter proportional to their down-weighting in robust regression analyses. The sizes of shapes at tree tips are proportional to log10(mass), and silhouettes are indicative of approximate relative size within some clades. The result from one tree calibrated to stratigraphy by imposing a minimum branch duration of 1 Ma is shown; other trees and calibration methods retrieve similar results. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853

"Dinosaurs aren't extinct; there are about 10,000 species alive today in the form of birds. We wanted to understand the evolutionary links between this exceptional living group, and their Mesozoic relatives, including well-known extinct species like T. rex, Triceratops, and Stegosaurus," said Dr. Roger Benson of Oxford University's Department of Earth Sciences and leader of the study. "We found exceptional body mass variation in the dinosaur line leading to birds, especially in the feathered dinosaurs called maniraptorans. These include Jurassic Park's Velociraptor, birds, and a huge range of other forms, weighing anything from 15 grams to 3 tonnes, and eating meat, plants, and more omnivorous diets."

The team believes that small body size might have been key to maintaining evolutionary potential in birds, which broke the lower body size limit of around 1 kilogram seen in other dinosaurs.

"How do you weigh a dinosaur? You can do it by measuring the thickness of its leg bones, like the femur. This is quite reliable," said Dr. Nicolás Campione, of the Uppsala University, another member of the team. 'This shows that the biggest dinosaur Argentinosaurus, at 90 tonnes, was 6 million times the weight of the smallest Mesozoic dinosaur, a sparrow-sized bird called Qiliania, weighing 15 grams. Clearly, the dinosaur body plan was extremely versatile."

The team examined rates of body size evolution on the entire family tree of dinosaurs, sampled throughout their first 160 million years on Earth. If close relatives are fairly similar in size, then evolution was probably quite slow; conversely, if they're very different in size, then this implies that evolution was fast.

"What we found was striking. Dinosaur body size evolved very rapidly in early forms, likely associated with the invasion of new ecological niches. In general, rates slowed down as these lineages continued to diversify," said Dr David Evans at the Royal Ontario Museum, who co-devised the project. "But it's the sustained high rates of evolution in the feathered maniraptoran dinosaur lineage that led to birds – the second great evolutionary radiation of dinosaurs."

The evolutionary line leading to birds kept experimenting with different, often radically smaller, body sizes – enabling new body 'designs' and adaptations to arise more rapidly than among larger dinosaurs. Other dinosaur groups failed to do this, got locked in to narrow ecological niches, and ultimately went extinct.

This suggests that important living groups such as birds might result from sustained, rapid evolutionary rates over timescales of hundreds of millions of years, which could not be observed without fossils.

Drs Daniel Moen and Hélène Morlon of the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris, who are not connected with the study - though Morlon did the editorial review - wrote in an accompanying article, "What explains why some groups of organisms, like birds, are so species rich? And what explains their extraordinary ecological diversity, ranging from large, flightless birds, to small migratory species that fly thousands of kilometers every year? [Benson and colleagues] find that body-size evolution did not slow down in the lineage leading to birds, hinting at why birds survived to the present day and diversified. This paper represents one of the most convincing attempts at understanding deep time adaptive radiations."

Comments