There's a disturbing, though funny to outsiders, trend sweeping green conscious corporations on the coasts of the United States - flurries of emails between indignant employees talking about how long their cars have been plugged in.

Though subsidies and public relations campaigns for electric cars are everywhere to be found, improvements in batteries have been absent for decades. Unless we want acid rain to come roaring back, there needs to be an improvement. Electric car companies are not going to spearhead the research, they are enjoying their 1950s-style "planned obsolescence" and have no reason to cause people to buy cars less often.

But each car charger added to the electric grid is basically the same strain as adding another house - there has to be a smarter way to keep these vehicles from causing brown-outs during hot weather. Better batteries that can run a car more than 10 miles would be ideal but it's hard to wonder if government-controlled science is up to the task. Some progress is being made. Researchers working on lithium-sulfur batteries added a unique powdery nanomaterial, a metal organic framework, to the battery's cathode to capture problematic polysulfides that usually cause lithium-sulfur batteries to fail after a few charges.

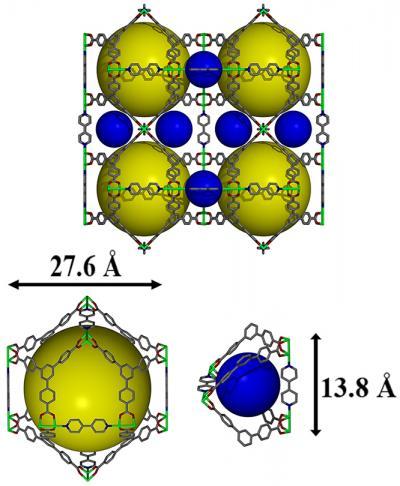

A nickel-based metal organic framework, shown here in an illustration, to hold onto polysulfide molecules in the cathodes of lithium-sulfur batteries and extend the batteries' lifespans. The colored spheres in this image represent the 3D material's tiny pores into with the polysulfides become trapped. Credit: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Today's electric vehicles are typically powered by lithium-ion batteries but lithium-ion batteries are severely limited in how much energy they can store. As a result, electric vehicle drivers are often anxious about how far they can go before needing to charge. One solution may be lithium-sulfur battery, which can hold as much as four times more energy per mass than lithium-ion batteries, which would enable electric vehicles to drive farther on a single charge, as well as help store more renewable energy.

The downside of lithium-sulfur batteries is they have a much shorter lifespan because they can't currently be charged as many times as lithium-ion batteries.

Energy Storage 101

The reason can be found in how batteries work. Most batteries have two electrodes: one is positively charged and called a cathode, while the second is negative and called an anode. Electricity is generated when electrons flow through a wire that connects the two. To control the electrons, positively charged atoms shuffle from one electrode to the other through another path: the electrolyte solution in which the electrodes sit.

The lithium-sulfur battery's main obstacles are unwanted side reactions that cut the battery's life short. The undesirable action starts on the battery's sulfur-containing cathode, which slowly disintegrates and forms molecules called polysulfides that dissolve into the liquid electrolyte. Some of the sulfur — an essential part of the battery's chemical reactions — never returns to the cathode. As a result, the cathode has less material to keep the reactions going and the battery quickly dies.

New materials for better batteries

Researchers worldwide are trying to improve materials for each battery component to increase the lifespan and mainstream use of lithium-sulfur batteries. For this research, Xiao and her colleagues honed in on the cathode to stop polysulfides from moving through the electrolyte.

Many materials with tiny holes have been examined to physically trap polysulfides inside the cathode. Metal organic frameworks are porous, but the added strength of PNNL's material is its ability to strongly attract the polysulfide molecules.

The framework's positively charged nickel center tightly binds the polysulfide molecules to the cathodes. The result is a coordinate covalent bond that, when combined with the framework's porous structure, causes the polysulfides to stay put.

"The MOF's highly porous structure is a plus that further holds the polysulfide tight and makes it stay within the cathode," said electrochemist Jianming Zheng of the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, co-author of the new work.

Metal organic frameworks — also called MOFs — are crystal-like compounds made of metal clusters connected to organic molecules, or linkers. Together, the clusters and linkers assemble into porous 3-D structures. MOFs can contain a number of different elements. PNNL researchers chose the transition metal nickel as the central element for this particular MOF because of its strong ability to interact with sulfur.

During lab tests, a lithium-sulfur battery with PNNL's MOF cathode maintained 89 percent of its initial power capacity after 100 charge-and discharge cycles. Having shown the effectiveness of their MOF cathode, PNNL researchers now plan to further improve the cathode's mixture of materials so it can hold more energy. The team also needs to develop a larger prototype and test it for longer periods of time to evaluate the cathode's performance for real-world, large-scale applications.

PNNL is also using MOFs in energy-efficient adsorption chillers and to develop new catalysts to speed up chemical reactions.

"MOFs are probably best known for capturing gases such as carbon dioxide," said materials chemist Jie Xiao of the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. "This study opens up lithium-sulfur batteries as a new and promising field for the nanomaterial."

In January, a Nature Communications paper by Xiao and some of her PNNL colleagues described another possible solution for lithium-sulfur batteries: developing a hybrid anode that uses a graphite shield to block polysulfides.

This research was funded by the Department of Energy's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Researchers analyzed chemical interactions on the MOF cathode with instruments at EMSL, DOE's Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory at PNNL.

Source: DOE/Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Comments