Photogrammetry is a method that uses two-dimensional images of an archaeological find to construct a 3-D model and it doesn't require special glasses or advanced equipment. Coupled with precise measurements of the excavation, photogrammetry can create a complete detailed map of an archaeological excavation site while being more precise than older, more time-consuming methods.

This method is already being put to use by archaeologists. When a possible Viking grave was found in Skaun in Sør-Trøndelag in 2014, the excavation site was mapped using photogrammetry.

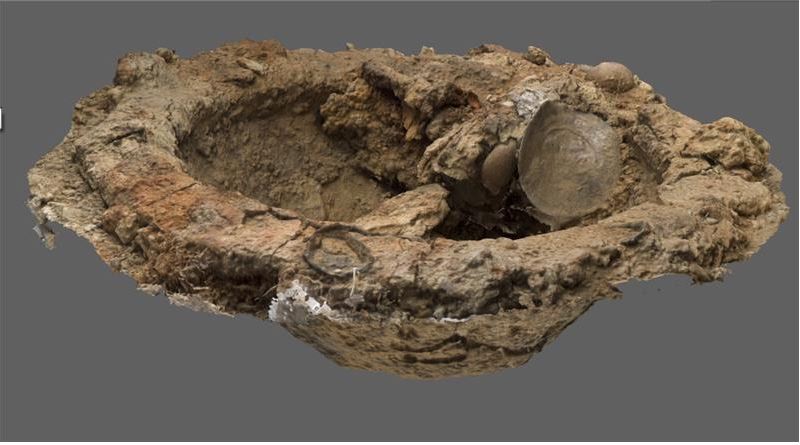

A shield boss found in what is likely a Viking’s grave in Skaun. Photo: NTNU University Museum

“This is still a very new technique,” say archaeologists Raymond Sauvage and Fredrik Skoglund of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's University Museum.

A Russian company has developed the program that they’re using at the museum, and it provides the kind of quality and detail that you could only dream of a few years ago. Even though the method requires some work, it still saves a lot of time.

“In one day, you can get three million measurement points. Before, we were satisfied with 3,000,” they say. And those 3,000 points could take a long time to find. This method can save archaeologists weeks of work with tape measures, sketching paper and cameras. The practical work in the field goes much quicker. Similar results have been achieved in the past using laser equipment and early versions of a photogrammetry program. But this has been very expensive, and takes a lot of time and resources.

A photogrammetry program only costs a few hundred euros, making it much more widely available, and three or four pictures from different angles are enough to make a simple 3-D model, although more images will provide a higher quality model. You can use any normal camera. It is also possible to use images of old finds to build a 3-D model based on them. For example, you could make a model using photos from previous excavations of Viking graves, and use this to explore how an excavation site changes over time.

Marine archaeologist Skoglund has tried this with the Dutch ship “De Grawe Adler” (the Grey Eagle), which sank in 1696 by Strømsholmen in Hustadvika, on the coast of central Norway and was discovered in 1982 when dredging for sand destroyed parts of the ship. “I swam along the whole length of the wreck a few years ago and took pictures,” Skoglund says.

He did so without ever considering the possibility of making a 3-D model of the wreck. The fact that the photos were taken underwater makes it slightly harder to put them together, but it is by no means impossible. If the results are precise enough, they can be used to monitor the decomposition of the ship. Finds under water tend to be particularly fragile, but decomposition can be difficult to see. You can’t just dive down every few years to make sure that everything is OK. With this new method, the decomposition can be measured much more precisely, and appropriate protection measures can be put in place.

The future

The next step is likely to be able to put on a pair of 3D-glasses and virtually walk into an excavation site, although that may be a few years in coming. There is one challenge — storing measurements digitally in a manner that will be useful for generations to come. Archaeologists working today are behind measurements and notes on excavations that may be used hundreds of years in the future. A paper photo taken 100 years ago is just as good now as it was then, as long as you have it on hand. But nobody knows if a PDF file will be of use in year 2115.

This is a challenge facing all information that is stored digitally. And it’s something that we can’t overcome without some planning.

Comments