For mammals, the outer ears of mammals play an important function in helping identify sounds coming from different elevations.

Since birds have no external ears, how do they accomplish the same thing? They utilize their entire head, according to a new paper in PLOS ONE

"Because birds have no external ears, it has long been believed that they are unable to differentiate between sounds coming from different elevations," explains Hans A. Schnyder, Technische Universitaet Muenchen

Chair of Zoology. "But a female blackbird should be able to locate her chosen mate even if the source of the serenade is above her."

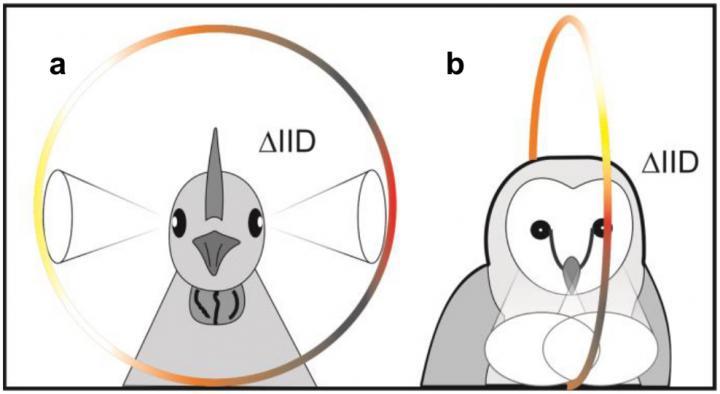

Lateral eyed birds like black birds, ducks or crows can discern the height of lateral sounds very precisely dependent to the sound volumes. Frontal eyed birds like the barn owl has specific hearing capacities for frontal sounds. Credit: Schnyder HA, Vanderelst D, Bartenstein S, Firzlaff U, Luksch H (2014) The Avian Head Induces Cues for Sound Localization in Elevation. PLoS ONE 9(11): e112178. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0112178

The head does the work of external ears

By studying three avian species - crow, duck and chicken - Schnyder discovered that birds are also able to identify sounds from different elevation angles. It seems that their slightly oval-shaped head transforms sound waves in a similar way to external ears.

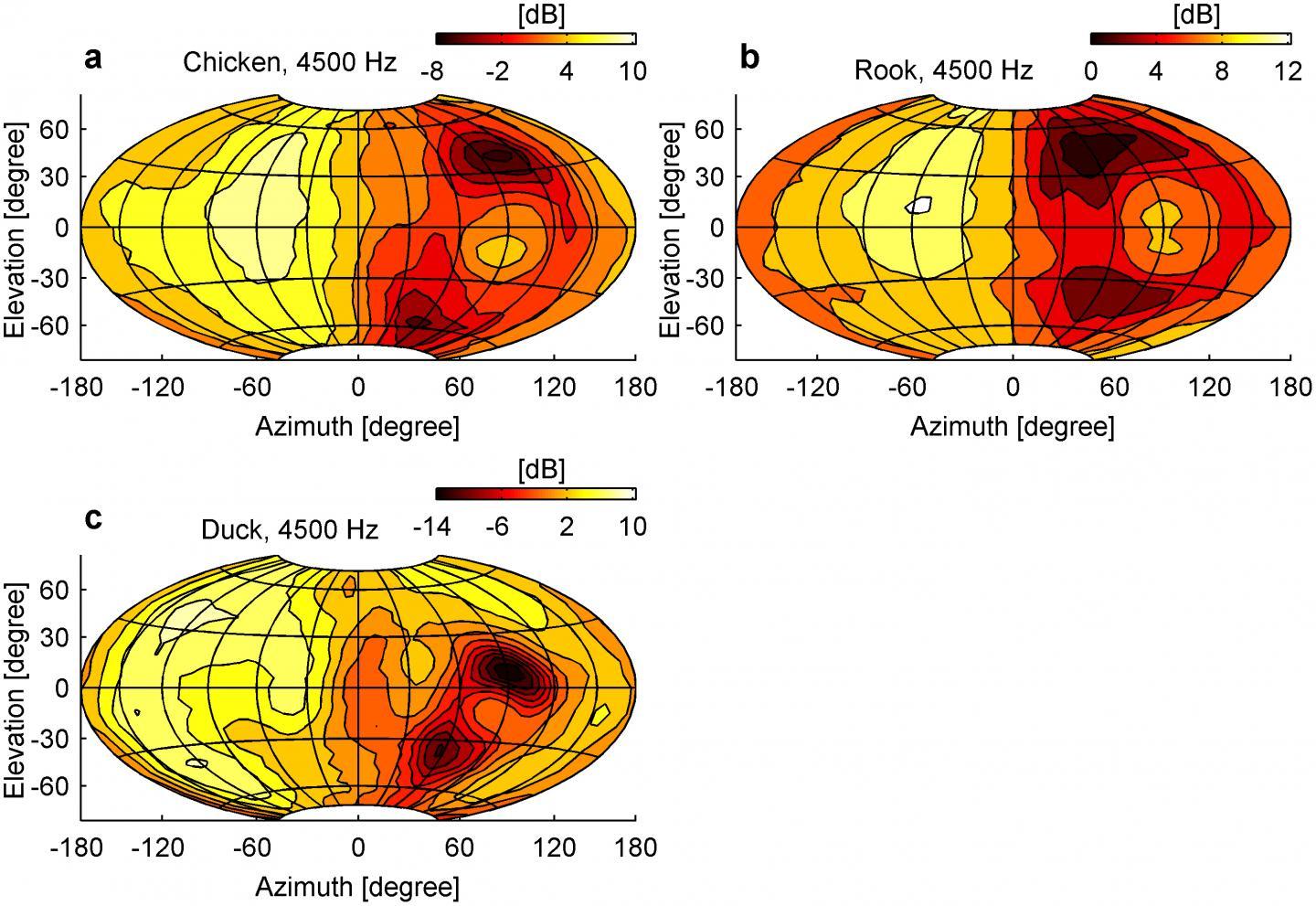

"We measured the volume of sounds coming from different angles of elevation at the birds' eardrums," relates Schnyder. All sounds originating from the same side as the ear were similarly loud, regardless of their elevation. The ear on the opposite side of the head registered different elevations much more accurately - in the form of different volume levels.

Different volume levels reveal sound sources

It all comes down to the shape of the avian head. Depending on where the sound waves hit the head, they are reflected, absorbed or diffracted. What the scientists discovered was that the head completely screens the sound coming from certain directions. Other sound waves pass through the head and trigger a response in the opposite ear.

The avian brain determines whether a sound is coming from above or below from the different sound volumes in both ears. "This is how birds identify where exactly a lateral sound is coming from - for example at eye height," continues Schnyder. "The system is highly accurate: at the highest level, birds can identify lateral sounds at an angle of elevation from -30° to +30°."

Interaction between hearing and sight improves orientation

Why have birds developed sound localization on the vertical plane? Most birds have eyes on the sides of their heads, giving them an almost 360° field of vision. Since they have also developed the special ability to process lateral sounds coming from different elevations, they combine information from their senses of hearing and vision to useful effect when it comes to evading predators.

The figures display the sound volumes displayed at the right ear for multiple sound positions -- for chicken, rook and duck, respectively. Credit: Schnyder HA, Vanderelst D, Bartenstein S, Firzlaff U, Luksch H (2014) The Avian Head Induces Cues for Sound Localization in Elevation. PLoS ONE 9(11): e112178. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0112178

A few birds of prey like the barn owl have developed a totally different strategy. This species hunts at night, and like humans its eyes are front-facing. The feather ruff on their face modifies sounds in a similar way to external ears. The owl hears sounds coming from in front of it better than the other bird species studied by Schnyder.

So there is a perfect interaction between the information they hear and the information they see - as earlier studies were able to demonstrate. "Our latest findings are pointing in the same direction: it seems that the combination of sight and hearing is an important principle in the evolution of animals," concludes Schnyder.

Comments