At one time, eagles were endangered due to a shrinking habitat and, to a lesser extent, poaching. Today, wind turbines are a major threat. Unlike with hunting or land development law breaking, no wind turbine company has gotten anything more than a token fine for killing any eagle. Yet along with over 1200 other raptors, an estimated 70 golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) are killed annually at even a single large wind farm - the Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area near Livermore California - a heavy toll on a species that reproduces slowly and can live up to 30 years. The wind farm is famous for being an environmental boondoggle, built in 1981 under the claim that wind power was viable and sustainable, and has since lost billions of dollars. The other claim was that birds would not be impacted. Today, golden eagle numbers have dropped by 80% in northern California and they won't nest near what was once their prime habitat.

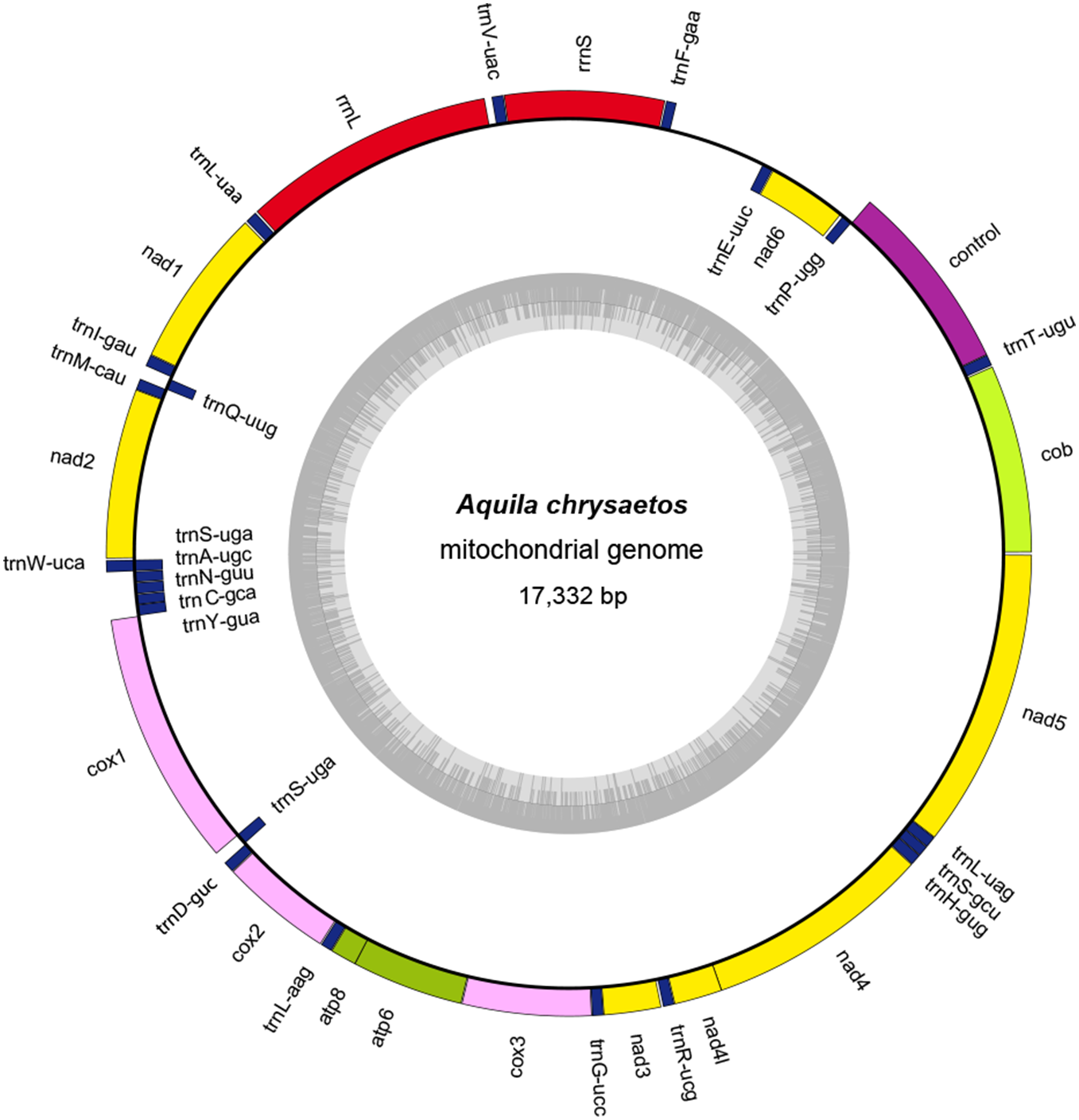

A. chrysaetos mitochondrial genome map. Cox1, cox2 and cox3 indicate cytochrome oxidase subunits 1–3; cob indicates cytochrome b; atp6 and atp8 indicate ATPase subunits 6 and 8; nad1–nad6 indicate NADH dehydrogenase subunits 1–6. Transfer RNA genes are designated by single-letter amino acid codes. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095599

Wind turbines may be a permanently entrenched political subsidy so wildlife biologists have been tasked with finding other ways to reduce deaths. One recently proposed method of reducing turbine-related eagle deaths was to coat wind turbines with ultraviolet-reflective paint, thereby heightening their visibility to eagles, because they are sensitive to ultraviolet light.

But now researchers have sequenced the genome of the golden eagle and found that these modern raptors might not be as sensitive to ultraviolet light as previously thought - instead, eagle vision is rooted in the violet spectrum - like human sight - rather than the ultraviolet.

The researchers generated the genome by extracting DNA from a blood sample of a golden eagle captured with a spring-loaded net in California. The eagle was outfitted with a GPS tracking device before its release, making it possibly the first animal to have its genome sequenced and be tracked at the same time.

"We find little genomic evidence that golden eagles are sensitive to ultraviolet light,"says Dr. Jacqueline Doyle, a postdoctoral research associate at Pursie and first author of a recent paper on the genome. "Painting wind turbines with ultraviolet-reflective paint is probably not going to prevent eagles from colliding with turbines."

Analysis of the genome also revealed that golden eagles have far more genes associated with smell than previously realized, indicating that the birds might use smell to locate prey more than researchers thought.

J. Andrew DeWoody, a Purdue professor of genetics and the study's senior author, said the markers would also help scientists track the evolution of different families of genes and identify potential golden eagle pathogens, parasites and symbiotic organisms.

Golden Eagle. Credit: Purdue.

Citation: Doyle JM, Katzner TE, Bloom PH, Ji Y, Wijayawardena BK, et al. (2014) The Genome Sequence of a Widespread Apex Predator, the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos). PLoS ONE 9(4): e95599. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095599

Comments