Scientists at Jet Propulsion Lab in California, the University of Colorado and the University of Central Florida in Orlando teamed up to analyze the plumes of water vapor and ice particles spewing from the moon. They used data collected by the Cassini spacecraft's Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVIS). Cassini was launched from the Kennedy Space Center in 1997 and has been orbiting Saturn since July 2004.

The team, including UCF Assistant Professor Joshua Colwell, found that the source of plumes may be vents on the moon that channel water vapor from a warm, probably liquid source to the surface at supersonic speeds. The team's findings are reported in Nature.

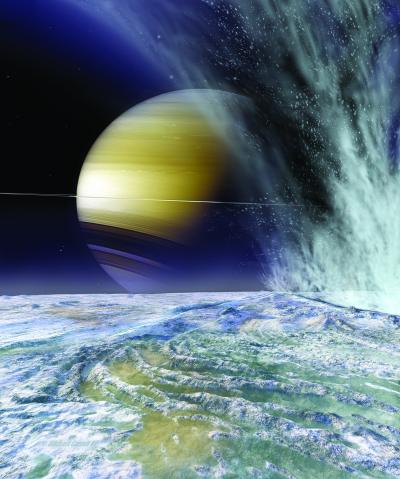

"There are only three places in the solar system we know or suspect to have liquid water near the surface," Colwell said. "Earth, Jupiter's moon Europa and now Saturn's Enceladus. Water is a basic ingredient for life, and there are certainly implications there. If we find that the tidal heating that we believe causes these geysers is a common planetary systems phenomenon, then it gets really interesting."

The team's findings support a theory that the plumes observed are caused by a water source deep inside Enceladus. This is not a foreign concept. On earth, liquid water exists beneath ice at Lake Vostok, Antarctica.

Scientists suggest that in Enceladus's case, the ice grains would condense from the vapor escaping from the water source and stream through the cracks in the ice crust before heading into space. That's likely what Cassini's instruments detected in 2005 and 2007, the basis for the team's investigation.

The team's work also suggests that another hypothesis is unlikely. That theory predicts that the plumes of gas and dust observed are caused by evaporation of volatile ice freshly exposed to space when Saturn's tidal forces open vents in the south pole. But the team found more water vapor coming from the vents in 2007 at a time when the theory predicted there should have been less.

"Our observations do not agree with the predicted timing of the faults opening and closing due to tidal tension and compression," said Candice Hansen, the lead author on the project. "We don't rule it out entirely . . . but we also definitely do not substantiate this hypothesis."

Instead, their results suggest that the behavior of the geysers supports a mathematical model that treats the vents as nozzles that channel water vapor from a liquid reservoir to the surface of the moon. By observing the flickering light of a star as the geysers blocked it out, the team found that the water vapor forms narrow jets. The authors theorize that only high temperatures close to the melting point of water ice could account for the high speed of the water vapor jets.

Although there is no solid conclusion yet, there may be one soon. Enceladus is a prime target of Cassini during its extended Equinox Mission, underway now through September 2010.

The team of researchers also includes Brad Wallis, and Amanda Hendrix from Jet Propulsion Laboratory; Larry Esposito (principal investigator of the UVIS investigation), Bonnie Meinke and Kris Larsen from the University of Colorado; Wayne Pryor from Central Arizona College; and Feng Tian, from NASA's postdoctoral program.

"We still have a lot to discover and learn about how this all works on Enceladus," Colwell said. "But this is a good step in figuring it all out."

Comments