Blue stragglers are found throughout the Universe in globular clusters - collections of about 100, 000 stars, tightly bound by gravity. According to conventional theories, the massive blue stragglers found in these clusters should have died long ago because all stars in a cluster are born at the same time and should therefore be at a similar phase. These massive rogue stars, however, appear to be much younger than the other stars and are found in virtually every observed cluster.

Dr Christian Knigge from Southampton University, who led the study, comments, "The origin of blue stragglers has been a long-standing mystery. The only thing that was clear is that at least two stars must be involved in the creation of every single blue straggler, because isolated stars this massive simply should not exist in these clusters."

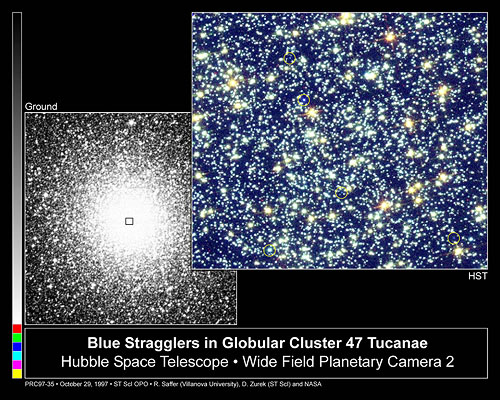

CLICK IMAGE FOR FULL SIZE. The core of globular cluster 47 Tucanae is home to many blue stragglers, rejuvenated stars that glow with the blue light of young stars. A ground-based telescope image (on the left) shows the entire crowded core of 47 Tucanae, located 15,000 light-years away in the constellation Tucana. Peering into the heart of the globular cluster's bright core, the Hubble Space Telescope's Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 separated the dense clump of stars into many individual stars (image on right). Some of these stars shine with the light of old stars; others with the blue light of blue stragglers. The yellow circles in the Hubble telescope image highlight several of the cluster's blue stragglers. Analysis for this observation centered on one massive blue straggler. Astronomers theorize that blue stragglers are formed either by the slow merger of stars in a double-star system or by the collision of two unrelated stars. For the blue straggler in 47 Tucanae, astronomers favor the slow merger scenario. This image is a 3-color composite of archival Hubble Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 images in the ultraviolet (blue), blue (green), and violet (red) filters. Color tables were assigned and scaled so that the red giant stars appear orange, main-sequence stars are white/green, and blue stragglers are appropriately blue. The ultraviolet images were taken on Oct. 25, 1995, and the blue and violet images were taken on Sept. 1, 1995. Credit: Rex Saffer (Villanova University) and Dave Zurek (STScI), and NASA.

Professor Alison Sills from the McMaster University explains further, "We've known of these stellar anomalies for 55 years now. Over time two main theories have emerged: that blue stragglers were created through collisions with other stars; or that one star in a binary system was 'reborn' by pulling matter off its companion."

The researchers looked at blue stragglers in 56 globular clusters. They found that the total number of blue stragglers in a given cluster did not correlate with predicted collision rate dispelling the theory that blue stragglers are created through collisions with other stars.

They did, however, discover a connection between the total mass contained in the core of the globular cluster and the number of blue stragglers observed within in. Since more massive cores also contain more binary stars, they were able to infer a relationship between blue stragglers and binaries in globular clusters. They also showed that this conclusion is supported by preliminary observations that directly measured the abundance of binary stars in cluster cores. All of this points to "stellar cannibalism" as the primary mechanism for blue straggler formation.

Dr Knigge says, "This is the strongest and most direct evidence to date that most blue stragglers, even those found in the cluster cores, are the offspring of two binary stars. In our future work we will want to determine whether the binary parents of blue stragglers evolve mostly in isolation, or whetherdynamical encounters with other stars in the clusters are required somewhere along the line in order to explain our results."

Funded in part by the UK's Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) and carried out by scientists at Southampton University and the McMaster University in Canada.

"A binary origin for 'blue stragglers' in globular clusters", Nature, 15 January, 2009.

Comments