What is less known is how much water occupied the red planet and what happened to it during its geological march to the present. Mostly, evidence has pointed to a period when clay-rich minerals were formed by water, followed by a drier time, when salt-rich, acidic water affected much of the planet. Assuming that happened, the thinking goes, it would have been difficult for life, if it did exist, to have survived and for scientists to find traces of it.

Now a research team has found evidence of carbonates, a long-sought mineral that shows Mars was home to a variety of watery environments — some benign, others harsh — and that the acidic bath the planet endured left at least some regional pockets unscathed. If primitive life sprang up in pockets that avoided the acidic transformation, clues for it may remain.

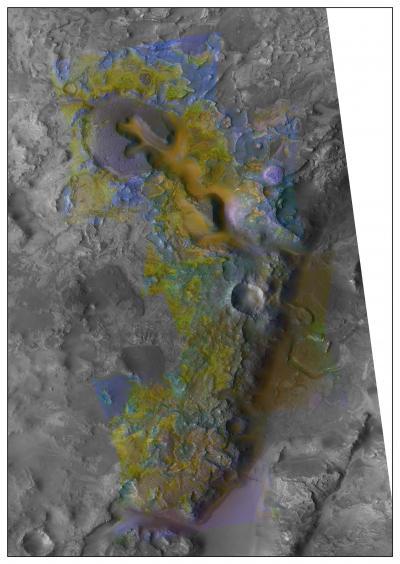

Carbonate-bearing rocks in the sides of eroded mesas in the Nili Fossae region. Scientists believe the carbonates may have been formed at the surface when olivine-rich rocks were exposed, and altered, by running water. Credit: NASA/JPL/JHUAPL/University of Arizona/Brown University

"Primitive life would have liked it," said Bethany Ehlmann, a Brown graduate student and lead author of the paper that appears in the Dec. 19 edition of Science. "It's not too hot or too cold. It's not too acidic. It's a 'just right' place.'

Finding carbonates indicates that Mars had neutral to alkaline waters when the minerals formed in the mid-latitude region more than 3.6 billion years ago. Carbonates dissolve quickly in acid, therefore their survival challenges suggestions that an exclusively acidic environment later cloaked the planet.

The carbonates showed up in the most detail in two-dozen images beamed back by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars, an instrument aboard the NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Scientists found the mineral near a trough system called Nili Fossae, which is 667 kilometers (414 miles) long, at the edge of the Isidis impact basin. Carbonates were seen in a variety of terrains, including the sides of eroded mesas, sedimentary rocks within Jezero crater and rocks exposed on the sides of valleys in the crater's watershed. The researchers also found traces of carbonates in Terra Tyrrhena and in Libya Montes.

NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander recently found carbonates in soil samples, and researchers had previously found them in Martian meteorites that fell to Earth and in windblown Mars dust observed from orbit. However, the dust and soil could be mixtures from many areas, so the origins of carbonates have been unclear. The latest observations indicate carbonates may have formed over extended periods on early Mars and also point to specific locations where future rovers and landers could search for possible evidence of past life.

"This is opening up a range of environments on Mars," said John "Jack" Mustard, a Brown professor of geological sciences and a co-author on the Science paper. "This is highlighting an environment that to the best of our knowledge doesn't experience the same kind of unforgiving conditions that have been identified in other areas."

The researchers, including Brown graduate student Leah Roach and scientists from NASA, the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, the Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale at the University of Paris, the U.S. Geological Survey, Cornell University and the University of Nevada, have multiple hypotheses for how the carbonate-bearing rocks were formed and the origin of the water that shaped them. They may have been formed by slightly heated groundwater percolating through fractures in olivine-rich rocks. Or, they may have been formed at the surface when olivine-rich rocks were exposed and altered by running water. Yet another theory is the carbonates precipitated in small, shallow lakes. Either way, such environments would have boded well for primitive life forms to emerge.

"We know there's been water all over the place, but how frequently have the conditions been hospitable for life?" Mustard said. "We can say pretty confidently that when water was present in the places we looked at, it would have been a happy, pleasant environment for life."

Comments