Within the past decade, we began to hear the term “patent cliff”—the consequence of most blockbuster drugs losing patent protection during a short period of time. Perennial critics of the pharmaceutical industry were experiencing paroxysms of joy as the holy grail of health care savings—generic drug companies—became able to sell cheap copies of formerly multi-billion dollar products.

The greedy drug companies would finally get their comeuppance, which would result in the rest of us buying the same medicines for pennies on the dollar from the saintly generic drug industry. What could possibly go wrong?

Plenty.

And should you be laboring under the false assumption that things worked as planned, I’m sorry to ruin your day. The saintly generic drug industry turned out to be something quite different. In fact by the end of this, you might think that some of their actions make big pharma look like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation by comparison.

For an excellent overview of what was supposed to happen, Elizabeth Fisher’s piece, entitled the “The patent cliff: rise of the generics,” which appeared on the pharmaceutical-technology.com website, is a great start. (But a bad finish).

Some of the key phrases in the article include:

“The arrival of the much-dreaded patent cliff, which has been haunting the global pharmaceutical for years, is finally here.” OK.

“Between 2011 and 2016, the world's best-selling drugs, with about $255bn in global annual sales, are set to go off patent.” Also true.

So far, so good. But then it heads south fast:

“The expected flood of generic drugs, which typically cost 20%-80% less than branded medications, will help to save patients a small fortune." Maybe on some other planet, but not this one.

"The lower price will benefit current patients and probably makes the product available to people who otherwise would not have been able to afford it if they were in a position where they didn't have a health plan or an adequate pharmaceutical benefit coverage." Or not.

Yes— it is true that the expiration of the Lipitor patent (which cost me my job) has provided savings to patients. The same holds true for users of the blood thinner Plavix (clopidogrel), the antidepressant Cymbalta (duloxetine) and a bunch of other $1 billion+ blockbusters.

Did people save money on these drugs? You bet. How are generic manufacturers looking right now? Pretty lousy. And then some. How can this be?

Just in case you had any lingering hope for humanity, some of the stunts that some generic companies have been pulling lately ought to snap you back to reality.

Don’t blame me if this puts you in a bad mood. Much of it came from pharma superstar Ed Silverman, whose Pharmalot blog, now published in the Wall Street Journal, is one of the places to go to learn about all things pharmaceutical.

Silverman’s November 14th piece, “To the Moon: Will Rising Prices For Some Generic Drugs Never End?” documented the business practices of certain generic manufacturers, and it ain’t pretty.

My 2011 op-ed in the New York Post discussed how life-threatening shortages of common hospital drugs (this hasn’t improved since then) resulted, in part, from generic drug companies dropping products that weren’t making them enough money to continue to manufacture them.

What’s going on now may or may not be worse, but it is far more galling. Perhaps the worst from Silverman’s article: The price of doxycycline, a 50 year old drug that costs pennies to make, shot up from $0.20 per pill to $18.49 after the good folks at the Jordan-based generic company Hikma found itself in the enviable position of having a monopoly on the drug, which is first-line therapy for Lyme disease, and an important antibiotic for other bacterial infections.

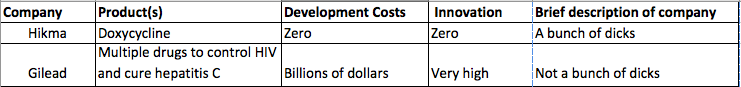

I find it ironic that a company like Gilead—the key player in the fight against both HIV and hepatitis C—regularly gets demonized for its high prices. Yes—they are high, but there are some subtle differences between the companies, as shown in the table below:

And while we’re on the subject, perhaps for the first time ever, I find myself agreeing with Bernie Sanders (C, VT). (Yes, I know “C” is really ”I” but I felt like putting it there anyhow). Prior to this I doubt we could have agreed where a suppository is supposed to go, but I’m completely with him on this. Sanders is holding Congressional hearings to address stuff like this:

-Digoxin, a drug for congestive heart failure, which has been in use for 200 years, and costs nothing to make rose from $0.11 to $1.02 per pill

-The ACE inhibitor Captopril—used to lower blood pressure went from $0.05 to $2.04 per pill.

-A bottle of 100 albuterol sulfate pills (used for asthma) rose from $11 to $434—enough to take your breath away.

-And, yesterday, for no particular reason, the price of naloxone (the antidote for opiate overdose) cartridges for nasal spray more than doubled in price, which will put a strain on the non-profit organizations that distribute them for free to addicts and their friends and families.

I have supported high drug prices in cases where innovative new drugs make a substantial difference in prolonging and improving human health (the exception being new cancer drugs that can typically cost in excess of $100,000 per course, and may provide only a few months of extra life).

But there is a world of difference between paying a ton of money to a company that actually does something useful and one that simply uses its status as a monopoly to suck money out of you.

They just plain suck.

Comments