But, with the right recipe it can become deaf and dumb rather quickly.Here is the recipe. Mix the following in equal quantities: Junk science and medicine, a misguided and politically-driven regulatory agency, a flawed legal system, predatory trial lawyers, a self-anointed know-nothing consumer "advocate," greed, and a company with deep pockets, and voila: the perfect mix.

There is no need to run this experiment; it was done 30 years ago at the expense of Dow Corning, the largest maker of silicone breast implants. What happened to the company and its employees was nothing short of criminal. And, because of a mind-boggling scenario that borders on something from The Twilight Zone, it is still going on—long after the implants were not only declared safe, but were returned to the market.

Dow Corning was only one of many victims of this travesty. In fact, most of those who suffered needlessly were women, especially those who needed reconstructive surgery following breast cancer—many of whom were subjected to additional emotional trauma simply from being told that there was a ticking time bomb within their bodies.

This appalling story is now a book. Silicone On Trial: Breast Implants and the Politics of Risk (Sager Group LLC, 2015) was written by Dr. Jack Fisher, a surgeon and professor emeritus of surgery at UC San Diego, who was in the middle of the whole mess. If there is a slightly angry undertone to the book, you will understand it very quickly.

When taken in its entirety, the story and its consequences are maddening.

Yet, the book is not a rant, but rather, a methodically researched chronicle of a three-decade debacle, which is supported by more than 400 footnotes. It may leave readers angry, or simply shaking their heads as they become aware of what was, and continues to be an atrocious miscarriage of justice. You should probably not read this book if you are already in a bad mood.

Do not invite Fisher and David Kessler, the commissioner of the FDA between 1990 and 1997, to the same party. Kessler earns a major "bad guy" role in the book, and even a quick glance at the chapter entitled "Science, Regulation, and the Politics of Risk" reveals this clearly. Fisher not only questions Kessler's scientific acumen, but his motives and ethics as well.

To preface Kessler's action, Fisher includes an almost-hilarious example of what can happen when agencies go bad.

Harvey Washington Wiley, the first commissioner of the FDA, "declared war" on Coca Cola for reasons that are still unclear today. Among other things, he accused the company of mislabeling its drink since it lacked cocaine(!). This culminated with US Marshals seizing a rather large shipment of Coca-Cola syrup from a Tennessee rail yard in 1909.

Fast forward 82 years, and history repeated itself as Kessler orchestrated a "stealth attack" against Bioplatsy, one of the companies that made silicone implants. This time, U.S. Marshals showed up unannounced, and seized 50 cases of the company's Misti Gold implants from a warehouse in St. Paul, Minnesota.

But Kessler was just getting started. His witch hunt expanded to include all silicone implants. In 1991, going against the advice of his own agency's expert panel, he ordered all silicone breast implants off the market, and urged surgeons to refrain from using the products. (Saline implants were not included in the moratorium.)

Kessler had an astounding ability to talk out of both sides of his mouth. Within two days of his decision, he appeared on daytime TV saying that there was "no [safety] data...simply no data after thirty years on the market," only to retract his own lie shortly thereafter, instead claiming that he had received "a lot of data but none of it was acceptable."

Although Kessler never approached the level of madness of Wiley, he did more damage. His fixation on silicone breast implants seemed all-consuming. Ignoring volumes of evidence of the safety of the chemical, which had been used without problem for 25 years, he continued his crusade. His biggest target, Dow Corning, paid the highest price.

Fisher's relationship with Kessler is, however, an absolute love fest compared to that with Dr. Sidney Wolfe—a self-appointed guardian of the American consumer with a superlative track record of being wrong so much of the time it may prompt the reader to revisit the old question of how many times per day a stopped clock is necessarily correct.

Wolfe, the co-founder of Public Citizen, has made a career of raising needless and alarmist warnings about drugs and other health related subjects. It has been said that "he never met a drug that he didn't dislike." Yet, this did not prevent him from being appointed to the FDA's Drug Safety and Risk Management Committee in 2009, despite the fact that he had been widely castigated for his alarmist recommendation that a thyroid medication be taken off the market. One year later, Wolfe was disqualified from an FDA panel on the risks of birth control pills since he had previously listed Yaz on his group's "do not use" list of 2002—something that Wolfe failed to disclose or even address.

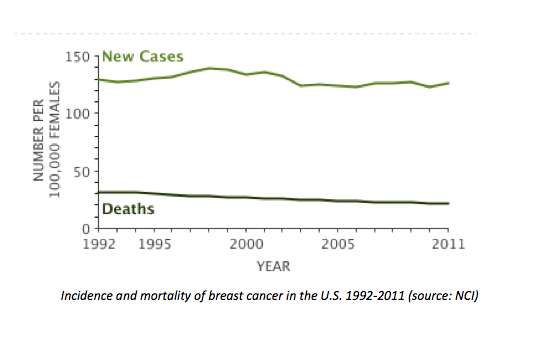

In the 1980s, Wolfe injected himself into the middle of the silicone controversy. His 1988 prediction on CNN that hundreds of thousands of cases of breast cancer would arise from silicone implants speaks volumes. How did that pan out? Just about as expected. The graph below (from the National Cancer Institute) pretty much says it all.

Media bias in cases like this is to be expected, but Fisher argues that no one could beat out Connie Chung for first prize. Chung, with the aid of her new show "Face to Face With Connie Chung," pursued this story with one-sided vigor, making use of half-truths, false claims and sensationalist images. Fisher writes "What CBS and the Face to Face team achieved that night [after an especially scary show filled with false claims] was a new low for one-sided fear mongering journalism."

Chung sees it differently. Regarding her participation in this matter she bragged, "It was one of the most important stories we've ever done." Which should make the reader wonder what other stories are on that list.

Our legal system doesn't come out of this smelling too good either. As a humorous aside, Fisher refers to an unnamed Judge in Texas "who declared the word ‘epidemiological’ inadmissible in his courtroom…too many syllables."

But, perhaps the most blatant miscarriage of justice is what followed.

In 1999, when a 400-page report by the Institute of Medicine was issued, there was finally an "answer." The report, written by an independent committee of 13 scientists, concluded that the silicone implants did not cause cancer, lupus, autoimmune disease, or anything else, other than localized problems (scarring and hardening) in rare cases when the implants ruptured.

Prior to declaring bankruptcy in 1995, Dow Corning reached an agreement to set aside $2 billion to cover all future product liability claims. Under the agreement, any woman who had silicone implants during this time would be guaranteed some portion of this settlement. So, of the $2 billion that Dow Corning was on the hook for, as of 2014, they have paid out $1.3 billion, and are still paying, long after silicone implants were shown to be safe, and were returned to the market.

In the end Dow Corning defended itself against 126,000 individual lawsuits, to defend a product that should have never been attacked in the first place. The lawyers behind these baseless suits got rich, and about 1,000 employees lost their jobs. The total cost to all companies that were forced to defend themselves was estimated to be $11 billion—$16 billion in today's dollars—for no good reason.

In his book, Fisher has documented far more abuses than could possibly be mentioned here. As they pile up—one after another—the reader will be left to wonder, "How was this even possible?"

Suggestion: Before you start reading, I recommend that you keep a bottle of Mylanta nearby, since you may very well suffer from gastric distress as you read. But, fear not. Mylanta contains a very effective ingredient to make you feel better. It's called simethicone. AKA silicone.

Comments