That streak ended on March 2nd, when the Times printed an editorial titled "Painkillers Abuses and Ignorance." The paper really dropped the ball on this one. After reading it, I was left wondering whose ignorance was being referred to, because in 433 words, they did nothing short of a superlative job of mixing together misleading statements, bad conclusions, and naive suggestions.

Taken at face value, a reader could only conclude that:

1. Opioid narcotics are not useful in relieving long-term pain.

2. There is a better solution.

3. The government can somehow fix it, rather than screwing it up worse.

All three are incorrect.

Point number one is very misleading, perhaps intentionally so. This can be inferred from the way the Times chose to word it: “The epidemic of deaths and addiction attributable to opioid painkillers continues unabated even as an authoritative new review of scientific studies has found no solid evidence that opioids are effective in relieving long-term chronic pain.”

It would be difficult to imagine how this could be interpreted as anything other than "narcotic pain-relieving drugs don't work for more than three months." This is utter nonsense, and perhaps disingenuous as well.

Here is another way to look at it: There may not be "solid evidence" of the benefit of long-term use of opioid narcotics, but it is undeniable that patients who are in dire need of pain relief will suffer mightily in the absence of these drugs.

And the statement itself is wrong, something that the Times touches on later in the editorial: [the lack of evidence of long-term effectiveness is] "in part because almost all the studies are of short duration."

This is echoed by Edward Covington, MD, the director of the Cleveland Clinic’s Neurological Disorder Center for Pain. He writes, “while opioids for cancer pain are ‘miracle drugs,’ [r]esearch does not exist for using opioids to treat chronic noncancer-related pain over long periods of time, especially in high-risk patients.”

No—narcotics do not stop working after three months. There is simply not enough evidence to prove that they do.

The second point—that there may be some solution to this around the corner—is worse. The Times writes, "it is extremely reckless to allow opioid usage and deaths to soar in the absence of proof that the treatment is effective."

This implies that there is an alternative to narcotic use that we should be exploiting, rather than just handing out pills. This could not be more wrong.

Douglas Throckmorton, MD, deputy director for regulatory programs at FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in 2012, “Increasing use [of opioids] has resulted in a clearly unacceptable increase in addiction, overdose, and death. We need to find better drugs."

As if it were so easy.

Heroin was first marketed In 1895 by Bayer, ironically, as a less addictive version of morphine, which was a big problem at the time. That didn't work out so well.

Here we are, 120 years later, and there is still no good way to control pain. Anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen and aspirin can cause serious gastrointestinal problems— specifically, gastric bleeding, ulcers, and kidney toxicity— especially when used long-term. Some people can't take them at all. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is far less effective, and can cause irreversible liver damage with long term use.

During this time we have seen the eradication of polio, smallpox, and other formerly-fatal diseases. We have also witnessed the discoveries of insulin, and antibiotics, the advent of cancer chemotherapy, and the taming of AIDS. Yet, we are barely better off in controlling pain than we were in 1895.

So, if you're expecting a magic drug that treats pain without baggage, don't hold your breath.

Perhaps more ironic, is the story of what happened following what is arguably the only example of "progress" against opioid abuse—the OxyContin story.

OxyContin is a high dose, time release oxycodone pill, which was designed to give long-lasting relief to patients with intractable pain. It worked pretty well, but it also became the poster child of modern drug abuse.

Addicts found that by simply grinding up the pill, they could get a very high dose—eight to 16 times that of a normal pill—which could then be smoked, snorted, or injected.

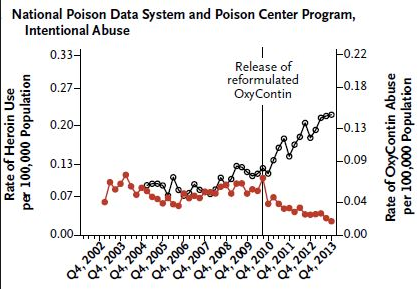

Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin worked for years to come up with a pill that was very close to “abuse proof,” and by 2010, they finally succeeded. When users tried to grind up the pill, it turned into a gum, which was difficult to use. OxyContin abuse dropped like a rock. Good, right? Not exactly:

As OxyContin became very difficult to abuse, addicts turned to heroin in droves. Its use more than doubled in two years. Is this progress?

It is not only not progress, but it actually made matters worse. Not only is heroin far more dangerous than oxycodone, but it is often "boosted" with a synthetic heroin called fentanyl, which is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. A tiny mistake in mixing or cutting can result in a deadly batch of heroin—an event that has been in the news quite often in recent months. And, let's not forget what happens when people who inject drugs share needles.

Addicts will find a way to get drugs, no matter what it takes. The unintended consequences of Purdue's success was to force addicts to switch to something far more dangerous.

I have written before about government attempts to curb narcotic abuse by moving Vicodin (hydrocodone) from DEA Schedule III up to Schedule II, which makes it much harder for patients to get. They now have to physically obtain a written prescription from their doctors, except in the case of emergencies, when doctors are allowed to prescribe a three day emergency supply by phone. Refills are not permitted, and a three month supply is the maximum.

Is this really what you want if you have intractable pain from terminal cancer, or other disabling conditions? To have an extra burden put upon you on top of the already-awful one you're already coping with?

In the end, we are left with a whole bunch of bad choices for the treatment of severe, chronic pain. But none of these is worse than denying people who are suffering from intractable pain, a measure of relief—something that is all but inevitable as doctors, knowing that the government is breathing down their necks, will be more reluctant to provide such relief to people who are in real need.

The "war on drugs" has been a dismal failure by any measure. Turning cancer patients and others with severe pain into collateral damage in this un-winnable war is inhuman.

Comments