If you are going to be a guru in the US, one tenet of yoga remains from the past - go with the flow. As the medical claims of yoga became more prevalent and yoga catapulted into a $10-billion-a-year enterprise, practitioners embraced new marketing success or fell by the wayside. Sanskrit names for postures and religious "om"-ing are out, 'feeling the burn' is in.

It's a marketing story that will be taught in classes for generations to come. There were 4.3 million practitioners in 2001 and now, riding a wave of Berly Bender Birch's "Power Yoga" book and expanding from there, that number is over 20 million, almost 500 percent more people in a decade and a half. Fencing instructors are probably scratching their heads wondering why their field has not taken off. They need to learn 'wellness' positioning techniques, I suppose.

There is no easy recipe for how to make such success happen. Yoga is not the first marketing engine powered by parallel logics for different personalities - people are convinced to invest their money for all kinds of reasons, education has a different value proposition to different groups, even coffee is sold as a lifestyle self-identification.

The beginning of yoga in the United States begins with Swami Vivekananda's speech representing Hinduism at the first World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893, Dr. Burcak Ertimur and Assistant Professor Gokcen Coskuner-Balli of Chapman University note in a recent article on institutional logics and brand management. Because it was mystical, people engaging in it embraced those enlightenment philosophical underpinnings: Raja yoga (mental) was more important than Hatha yoga (physical) because all people could be equal spiritually. In the 1960s and '70s, everyone in the United States gradually became demystified. By the end of the 1970s, we knew that Uri Geller could not bend spoons and the paranormal class at Princeton was still being taught but students were only taking it ironically.

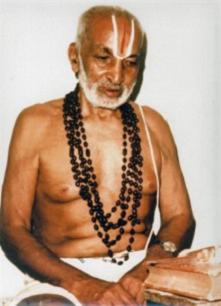

The 1960s created a drug culture and some people began to market yoga as a treatment for that but yoga burst into fad popularity and then back out again and it primarily stayed on the fringes. This century yoga contorted once more, but it became bigger than ever. Yoga gurus are no longer Indian men who sat through years of meditating, they are American women in tight Lululemon pants and they market yoga for recovery from injuries, pain management and with vague claims about staving off chronic health problems.

|  |

Once it became a large industry it was no surprise that studies sought to validate possible medical benefits, the same way there has been a rush to criminalize grain, sugar and, this year, to make Vitamin D the cause and cure of everything. The U.S. government's $125 million alternative medicine advocacy branch, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (now the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health), embraced it and then insurance companies had to cover yoga classes while we complained the cost of health insurance was too high.

Is yoga here to stay? It's hard to say. They are the third most popular type of fitness business right now but that does not mean much. Ertimur and Coskuner-Balli say that the largest chain is just 86 stores. That isn't quite a part of culture the way specialty coffees have become but we may see a Starbucks of yoga at some point.

Citation: Burçak Ertimur, Gokcen Coskuner-Balli, 'Navigating the Institutional Logics of Markets: Implications for Strategic Brand Management', Journal of Marketing Mar 2015, Vol. 79, No. 2 (March 2015) pp. 40-6 doi:10.1509/jm.13.0218

Comments