A generation ago, there were income statistics showing that people with college degrees earned more money than those without, so the federal government decided everyone should have a college degree. It didn't help with employment one bit, it just created a new barrier to entry. This century, government saw that people in STEM fields earn more than people with humanities degrees so they began to promote STEM careers.

Yet not all STEM degrees are equal. We may think that a 19th century poetry major is less employable than someone in STEM, but if that STEM PhD is in 'robot ethics', the job choices are going to be academia or nothing just the same. Individual ability still matters most so all those statistics we have seen stating that we need more X people in STEM is missing the real plot. Dr. Kelvin Droegemeier, Vice Chairman, National Science Board and Vice President for Research, University of Oklahoma summed it up nicely on a call today when he noted that saying everyone needs STEM degrees is like saying everyone needs to bring food to the church picnic. It's reasonable to want that, but if everyone brings potato salad it is a terrible picnic. You don't have to be born in Oklahoma to be Oklahoma practical that way. What we need to make sure of is that people who want to bring chicken can get to the picnic as easily as those carrying potato salad.

Yet in the legacy way of looking at statistics the big concern was the STEM equivalent of 'how many people are bringing food?' rather than 'people are going to want some chicken and some beans, how do we know who will be better at chicken than potato salad?'

One of the smart things they did in the new report is to stop simply looking at how many people are in STEM and how well they match the government's preferred demographic goals and instead examine how people got where they are. Looking at the pathway into and out of STEM careers can tell us if there is a problem and that is much more constructive than mandating a solution. It does not matter as much to society if there are fewer women in quantum physics like it does if there are not enough people in the medical field, so if STEM outreach is convincing smart women inclined to be doctors that they should instead go into physics, we have not really gained anything.

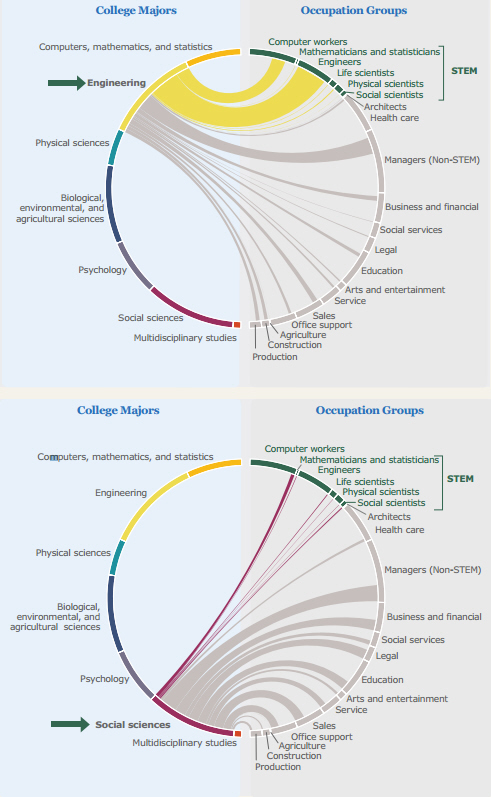

Here is Census Bureau data on pathways. You can see that engineering is going to lead to STEM jobs quite often while social sciences are going to lead to business and arts. Nothing wrong with that, but why someone with a STEM degree would end up doing office support, mal-employment, merits investigation.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2012 American Community Survey

If we see a lot of people in STEM are mal-employed - their degrees are irrelevant to the jobs they get - it's important to ask why. If someone moves to where there are no jobs in their field, because of a spouse or for lifestyle or the weather, there is not much that can be done to fix that so it shouldn't be an indictment of STEM overall. If someone got a degree in website design - they brought potato salad to the STEM picnic knowing there was already a lot there - then we are doing a disservice preaching STEM jobs without qualifying that they are not all equal.

H1B visas

The report also touches on one topic that remains controversial, and has been since the new restrictions were issued in the 1990s - the role of foreign workers. We make student visas easy to get and then we make work visas difficult. So we have been providing the best education in the world to people we forced to return home to become competitors to the US.

Critics argue that we don't need to turn more Americans into STEM people, we need to turn more STEM people into Americans, that's good for our economy and it's good for true diversity - the kind that does not get special check boxes on government forms. They have a point. Graduate student diversity in STEM is up - and that is a good thing. Preventing people who have lived here and want to remain from getting jobs is a relic of Clinton-era protectionism but proponents argue that foreign workers, even in the US, block out Americans.

Credentialism

A lot of the people who can't find jobs in STEM are not young people, they are in middle age. Older people are more expensive but they are not being undercut by cheap foreign workers, they are being undercut by cheap young ones who get advanced degrees in a credentialism arms race and lack a mortgage payment and aren't stuck in a school system their kids like.

That is not just a STEM issue, it is a geography issue and a lifestyle issue. We've been ill-served by broad generalizations and so it's good we can finally take a real look at who is a 'STEM worker'. The fact is STEM jobs have done quite well, even in a bad economy. Figuring out the best pathways to make sure more people have a chance to compete in those fields makes sense, in a way that throwing money at STEM advocacy campaigns never has.

As for me, I've been in STEM for over 20 years so I have seen a lot of potato salad. That's why I always try to make sure I bring some steak...with just enough sizzle.

Comments