It started with a problem in Transalpine Gaul (the French side of the Alps, Marseille and surrounding area) which happened to be a region that Caesar was responsible for, at a time when the shared leadership - the triumvirate - had two renowned military leaders already. Caesar was what we would today call a populist politician; he appealed to popular ideas that weren't much good, but they looked good (in Science Left Behind, the introduction talks about Congress replacing plastic spoons with spoons made from corn because they are biodegradable - they also did not work, had to be shipped on trucks to biodegrade and cost a lot more, but it appealed to environmentalists, who apparently don't know why people use spoons). He was competing with one commander who defeated the now-famous Spartacus and another who conquered Turkey.

So when the the Helvetii (now modern Switzerland) decided they needed to get away from the Germans moving closer and closer, the threat was to the Aedui, who were 'allies' to Rome and had the road from Italy to Spain running through the area. Caesar ended the threat in surprisingly efficient fashion and then decided to deal with the German issue. Rome liked stable, 'Roman' neighbors among the Celts, not conquesting German ones and Caesar had now gathered six legions and so off he went to become the most famous military leader in Roman history. The Gallic War would not end until after the uprising of Vercingetorix in 53 BC but it, and the people who fought the Romans, have fascinated historians since.

You'll forgive me for using the more commonly known general term 'Celt' when the Treveri were Belgic and 'Celtic' didn't become synonymous with the entire swath of barbarian hordes (1) until later, but this is not a History of Gaul and Germany, it is about archeology. And archaeologists have now confirmed the location of the oldest Roman military fortification known in Germany - outside the city of Trier, in the mountains between the Rhine and Maas rivers. The encampment is near an oppidum (an Iron Age fortress) "Hunnenring" or "Circle of the Huns" that the tribe called Treveri inhabited.

Roman camp gateway paving stones with a shoe nail between the stones. Credit: Sabine Hornung, Arno Braun

'Confirmed' is the operative word. Ruins have been known about by archaeologists since the 1800s, you can visit wall remains in the forest near Hermeskeil, but obviously in 2,000 years Germans chose to make the area more hospitable for living so a lot of the ruins are now farms and there was debate over what the ruins were, their extent and from when. Now a team has used radiocarbon dating and physical evidence to claim that the date and proximity mean it must have been used in the Gallic War against the Treveri.

"The remnants of this military camp are the first pieces of archaeological evidence of this important episode of world history," said Dr. Sabine Hornung of the Institute of Pre- and Protohistory at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz and lead author of the paper in a statement. "It is quite possible that Treveran resistance to the Roman conquerors was crushed in a campaign that was launched from this military fortress."

Especially given its size. Hornung and her team began their work at Hermeskeil in March of 2010, first to determine the size and shape of the camp. It's a big one, an almost rectangular rampart and ditch enclosure sized at around 18.2 hectares (182,000 square meters), so it had room for thousands of legionaries and cavalry. An extension controls a spring - their water supply. It all sounds very Roman. And it's 2 miles from the Celtic oppidum, which was abandoned around that time.

They uncovered a gateway with the nails and stones (shown above). The shoe nails are what were used in the sandals of Roman soldiers, a clear indications that the ruins of Hermeskeil dated to the Gallic War. They also found pottery fragments that dated to the period.

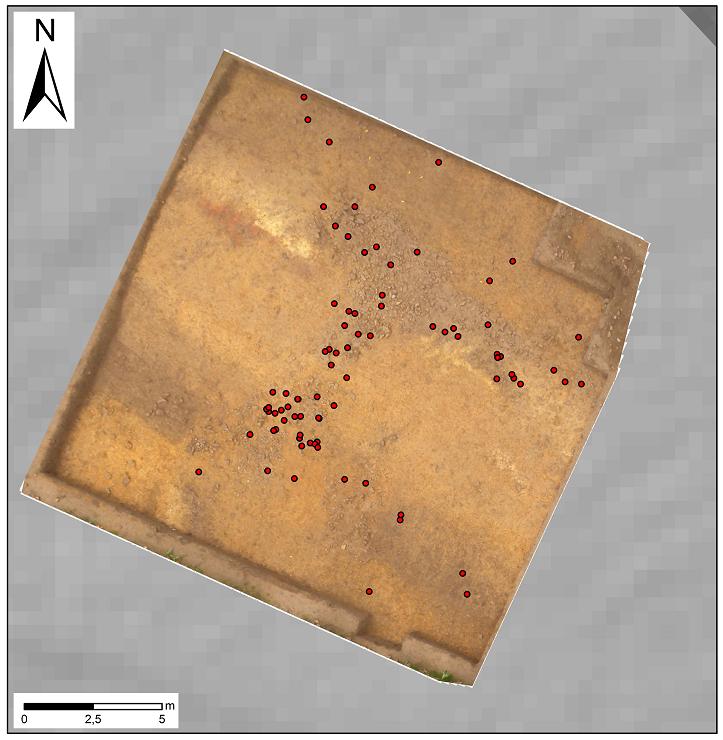

Exposed gateway of the camp at Hermeskeil with the remains of the stone pavement. The darker areas in the lower section mark the filled-in camp ditches while to the north there is a narrow berm behind which is the earthen wall to whose rear the remains of a scorched wickerwork construction were found. This served as a stabilizing support for the wall made of heaped soil that had been dug out of the ditches. The dots mark the different sites where shoe nails from the sandals of Roman soldiers were found. Credit: Sabine Hornung, Arno Braun

Correlation does not always equal causation but when it comes to big, organized armies against loosely connected tribes, it surely does. In his history, "de Bello Gallico" Caesar wrote that the Treveri, like most of the later so-called Celtic tribes, had both pro- and anti-Roman factions and that troublemakers led to the fighting. He seems to have respected them, he said they had the best cavalry in Gaul, and the Roman commander Labienus only had one legion. Given that, what led to their defeat? It's outside the scope of this piece but military experts say it was hesitance, they wanted to wait for more reinforcements to arrive but by the time that happened the Romans had three legions - and three legions were a lot more than three times the power of one.

Narratives by conquerors aside, it's nice to get some archaeological confirmation of that period in Italian/German relations,

Citation: S. Hornung, Ein spätrepublikanisches Militärlager bei Hermeskeil (Lkr. Trier-Saarburg). Vorbericht über die Forschungen 2010-2011, Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt, 42,2, 2012

NOTES:

(1) Including across the channel - while Campbells likely had to be Norman in origin, given the name, our family penchant for alcohol and headbutting suggests that culturally we were, and remain, more Scots Celt than the French kind.

Comments