One reason to err on the side of caution and not chase diet fads is that fads tend to be expensive and their benefit is unknown. A gluten-free diet, for example, will be 242 percent higher cost and the extra sugar, extra fat, hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose and xanthan gum in gluten-free foods are not a health positive.

What about the whole food diet?

The belief is that a whole food diet is 'eating as close to natural as possible' - that means no refined sugar or processed food. (1) The whole food diet is a process, like organic food in general, and it is based on a belief that the process must have a health benefit because people did it in the past. For example:

Other oils that were introduced more recently, such as canola oil and soybean oil, require complex processes and the use of chemical solvents, which does not fit the definition of whole foods.So buy olive oil, but only really expensive cold-pressed olive that peasants had to get arthritis to create. That's a rich people diet, not a science one, but it is harmless.

Except perhaps not harmless to everyone.

Writing in Neurobiology of Aging, Parrott et al. detail their study using a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's Disease and found that a whole food diet caused mice with their equivalent of Alzheimer's to do worse on tests of strategic learning and spatial memory.

Usually, researchers want to know if over-expression of amyloid precursor protein or tau causes the plaque or tangles commonly linked to Alzheimer's Disease, named after the fellow who discovered those qualities in diseased brains, Alois Alzheimer, a century ago. In this paper the researchers wanted to reconcile some animal models, which found that oxidative stress was important, and clinical trials, which showed no benefit using antioxidants that could modulate cell signaling and oxidative stress.

Basically, they wanted to see if there were real-world differences based on diet, so they weaned transgenic (TgCRND8) mice with a whole-food diet, things like salmon, blueberries, kale and brussel sprouts and such, or regular chow.

The results were a bit of a surprise. In mice with Alzheimer's, the whole food diet mice developed worse cognitive function than those fed the control diet - spatial memory and strategic rule learning declined.

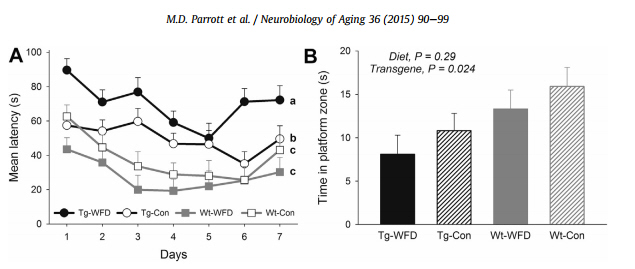

(A) During spatial memory acquisition, Alzheimer's mice on the whole food diet performed even worse than mice on a normal diet. There were no differences according to diet in the wild-type mice. (B) In the probe trial, Alzheimer's mice performed worse than the wild type. Credit: Parrott et. al.

There is a qualifier that prevents anyone from declaring a whole food diet bad the same way people selling diet fads are wrong for declaring it superior - there are a lot of factors, so it is difficult to be sure whether it is a composite effect or an abundance of one component.

The whole food diet was heavy in vegetables that contained high amounts of glucosinolate phytochemicals, which have been found to generate reactive oxygen species in animal models - which should be a good thing, especially when it comes to things like preventing cancer, but might be bad in someone who already has amyloid-beta deposition.

Citation: Matthew D. Parrott, Gordon Winocur, Richard P. Bazinet, David W.L. Ma, Carol E. Greenwood, 'Whole-food diet worsened cognitive dysfunction in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model', Neurobiology of Aging 36 (2015) 90e99 DOI: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.08.013

NOTE:

(1) Other than that, it is basically a low-carb diet, eat one piece of bread a day or the equivalent. Outside those parameters, it is more psychological, with advice like eating free-range eggs. Why don't regular eggs provide the same health halo, since they have no difference at all nutritionally? It's a narrative that sounds better.

Comments