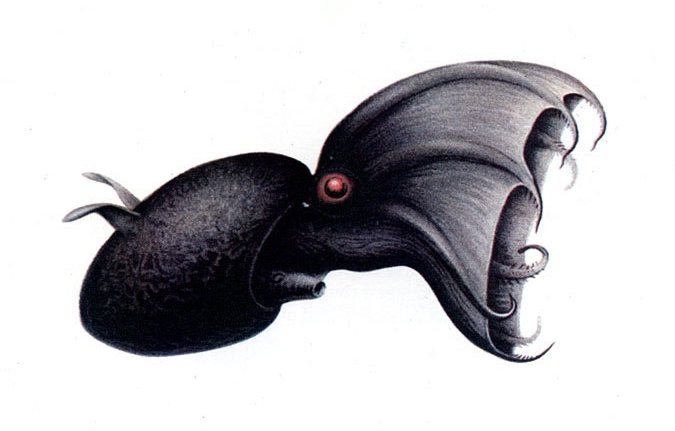

Vampire Squid And The Evolution Of Cephalopod Sex

Vampire Squid And The Evolution Of Cephalopod SexEveryone loves vampire squid, right? Their monstrous name belies their gentle nature as graceful...

Learning Science From Fiction: A Review Of Ryan Lockwood’s “Below”

Learning Science From Fiction: A Review Of Ryan Lockwood’s “Below”In last month’s review of Preparing the Ghost, I mentioned that you can actually learn facts...

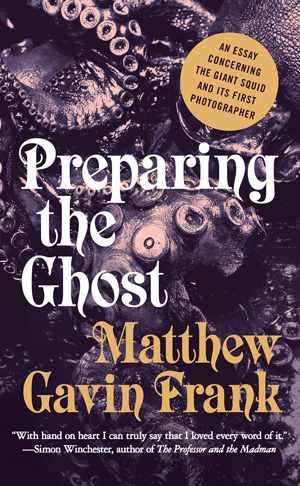

Usurped By Legend: A Review Of Matthew Gavin Frank’s ‘Preparing The Ghost’

Usurped By Legend: A Review Of Matthew Gavin Frank’s ‘Preparing The Ghost’When you read something in a book, do you believe it? You might say, “Of course not if it’s...

Squid Lady Parts

Squid Lady PartsThis Bobtail squid was imaged by the Deep Discover ROV in Atlantis Canyon, is less than one foot...