Excerpts from a very good book -

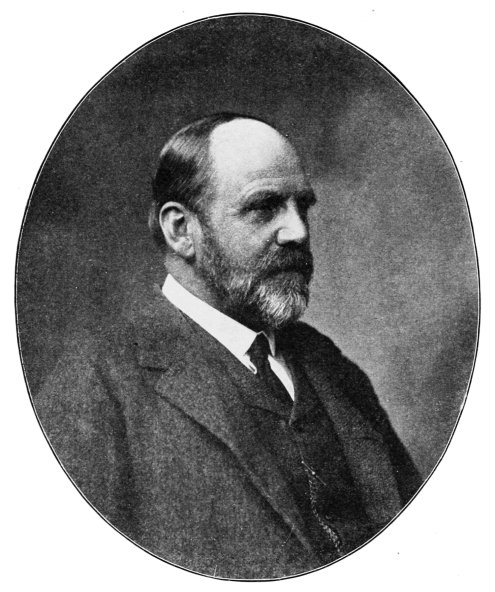

Rustic sounds and other studies in literature and natural history

by Sir Francis Darwin, 1917

I found this book by Sir Francis Darwin to be both an absorbing and easy read. Good science combines well with light humour, and Sir Francis Darwin achieves this combination in a masterly fashion.

The reference to 'boys' reflects the times of Sir Francis Darwin: it should now be read as 'boys and girls', of course.

I think that we all, who study science, hope to be the first to discover some exciting new fact -

"But in science the credit goes to the man who convinces the world, not to the man to whom the idea first occurs. Not the man who finds a grain of new and precious quality but to him who sows it, reaps it, grinds it and feeds the world on it."

Francis Darwin

First Galton Lecture before the Eugenics Society', Eugenics Review, 1914, 6, 9.

This excerpt from Darwin's book, below, brought back happy times as a child, when icy winters were very common in my part of England, namely Kent. They are not so common now: I have personally observed that the climate has definitely changed here since the 1950s.

Chapter I, Rustic Sounds

To children there is something impressive and almost sacred in the changes of the seasons, in the onset of winter, or the clear approach of spring. The first of these changes was heralded for me by the appearance of puddles frozen to a shining white; mysterious because the frost had drunk them dry in roofing them with ice, and especially delightful in the sharp crackling sound they gave when trodden on.

Chapter IX, Nullius in Verba

An Address on the occasion of the opening of the Darwin Laboratories at Shrewsbury School, October 20, 1911.

Excerpts from pages 143 - 151

I once heard Lord Rayleigh refer to the necessity of putting one's subject-matter clearly before an audience, and he illustrated his point by the following story. Somebody, possibly a lady, came from listening to a lecture by Mr. So-and-So, and when asked what it was about, replied, "He didn't say." I shall follow Lord Rayleigh's advice and tell you that my subject is "Why science should be learned." Why it is worth while for a boy to give up some of his time to this particular form of knowledge, and what advantage he may expect to gain from so doing.

There are many possible reasons for a boy's learning science.

I Because he is told to. This is an excellent reason, but not inspiriting.

II To get marks in an Entrance Scholarship examination. This is a virtuous reason but not intellectual.

III To gain knowledge which will be of use when he comes to follow a profession, and wants to know physics in view of becoming an engineer, or physiology as a part of medical training. This is a worthy reason, but not a common one.

IV Lastly, a boy may learn science because he wants to ; because he finds it entertaining ; because it satisfies an unreasoning desire to know how things in general work.

This is the best possible reason and the most efficient, and what I propose, is to inquire whether this wish to know something of science can be justified.

The word 'science' simply means knowledge, but it is usually applied to knowledge that can be verified. Thus we learn by heart that Queen Anne died in 1714. I believe this to be a fact, but I have no means of verifying it. But if I am told that putting chalk into acid will produce a heavy gas having the quality of extinguishing a lighted match, I can verify it. I can do the thing and see the results. I am now the equal of my teacher ; I know it in the same way that he does. It has become my very own fact, and it seems to have the satisfactory quality that possession gives. This characteristic of scientific knowledge is not always recognised, I mean the profound difference between what we know and what we are told. When science began to flourish at Cambridge in the 'seventies, and the University was asked to supply money for buildings, an eminent person objected and said, "What do they want with their laboratories? — why can't they believe their teachers, who are in most cases clergymen of the Church of England ?' This person had no conception of what the word 'knowledge' means as understood in science.

Another characteristic of science is that it makes us able to predict. I have already referred to the fact that Queen Anne is dead, and we know, or are told, that she died, as I said before, in 1714 ; we also know that George I died in 1727, and George II in 1760, but that would not enable us to predict that George III would die in 1820. They are isolated facts not connected by the causal bond that knits together a series of scientific truths. And this is after all a fortunate thing for the peace of mind of reigning sovereigns.

...

There is a dramatic effect in even the simplest of experiments. I, for one, am never weary of the time-honoured demonstration of a water-plant giving off oxygen as it assimilates. A twig of Elodea in a large beaker of water gives off no bubbles in the dull light at the back of the room, but when close to the window it does so. And with proper precautions the rate of bubbling becomes an accurate measure of the intensity of assimilation. To complete the demonstration the experiment should be repeated with water which has been boiled, and therefore roughly freed from CO2, when the rate of bubbling is very greatly diminished. Finally, by blowing vigorously into the water it may be charged once more with CO,, and the normal rate of bubbling may be established.

...

All who work at science may recognise that they belong to a guild which makes for the happiness of the human race. And this they must do, not with any pride, but humbly acknowledging how small is their personal share in the total of progress.

The Darwin Buildings, that is to say, the three new laboratories which are open to-day, were absolutely needed to carry out the Head Master's plan of giving every boy in the School a chance of learning science. When I say that at the present time 270 boys under five masters are at work in the laboratories, you will realise to what good use they are being put. As I happen to represent the Royal Society on your Governing Body it is especially satisfactory to me to know that science is here taught on the principle expressed by the motto of the Society : "Nullius in verba," that is to say, not in other people's words, but in your own observation lies the path of Science.

Excerpts from -

Rustic Sounds And Other Studies In Literature And Natural Historv

By Sir Francis Darwin, 1917

Free download, courtesy archive.org.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Comments