Many American journalists have dispatched any pretense of objectivity, according to

a new think tank report.

After attracting scorn with bizarre classifications of a weedkiller, bacon, and hot tea, the French statistics group known as the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) decided to puncture claims that activists had manipulated the process by doing a flip-flop on coffee. Though they were widely expected to increase the hazard designation from 1991's already bizarre "possibly carcinogenic", they suddenly reversed course and lowered a classification of a product for the very first time.

Pop culture is in a bit of a quandary. Though food is essential for life, culturally it is no longer a basic necessity, and that's thanks to science. We grow more food on less land than ever dreamed possible. Even Europe, with all its political limitations in agriculture. Food is a cheap commodity and that makes it a values issue.

RIP to Professor Murray Gell-Mann, who passed away last week and was famed (including a Nobel prize) for quark theory.

I never met him, but if you spent time at Caltech you probably did. He was not like Einstein, I am told, he was approachable if you were a young scientist, but you had to know what you were talking about.

A few years ago I taught a class there, invited by my friend the best-selling author and science journalist Greg Critser, who was an instructor for science journalism at the school. He had previously agreed to be on an AAAS panel I was moderating in San Francisco and I was returning the favor for him by being a guest speaker for his class at Caltech.

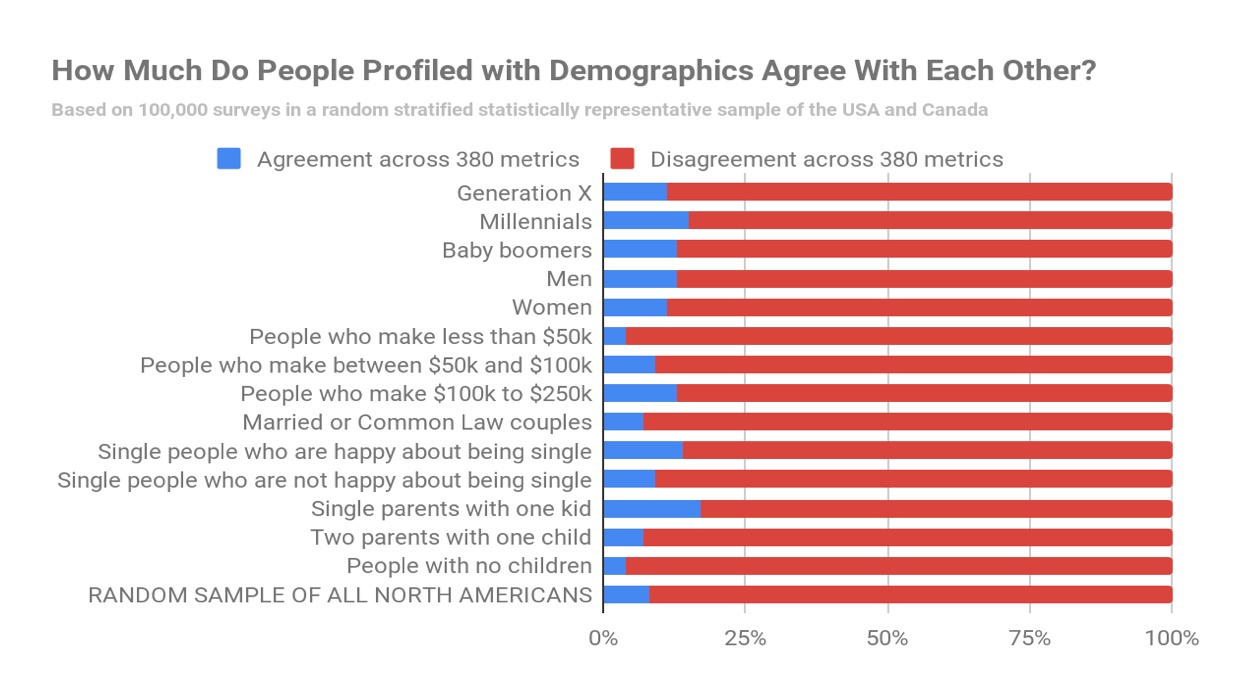

If you want to annoy someone in their late 30s, joke that all they care about are avocado toast points or beard grooming or running off to Coachella when a project needs to be finished. Because they are millennials.

You can also stereotype Baby Boomers or Generation X(1) and get a rise out of them. Everyone seems to know that these "generation" classifications were entirely manufactured by advertisers, but they caught on and have become part of the lexicon. Advertisers created these sweeping generalizations based on demographics.

Yet they may not be right at all. They may even be shockingly wrong.

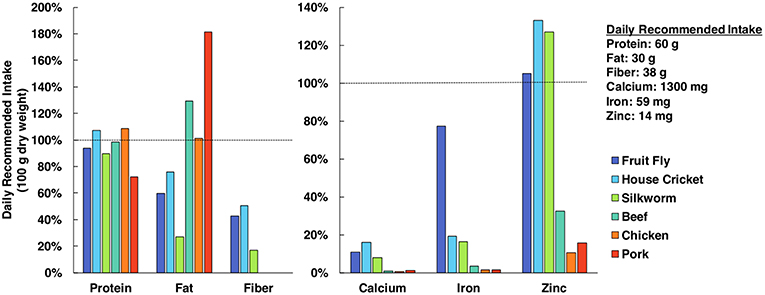

If you have cooked a steak or a hamburger you know that by the time you are ready to serve it, and certainly after you cut or bite into it, there will be liquid that oozes out of it.

Anti-meat groups know it isn't blood(1) but they use that imagery to try and sway people to their cause. And groups who make substitutes for meat also use that imagery, because they think that's important to meat eaters. Because marketing groups have long used it, people think it's blood, and even use the term "bloody."

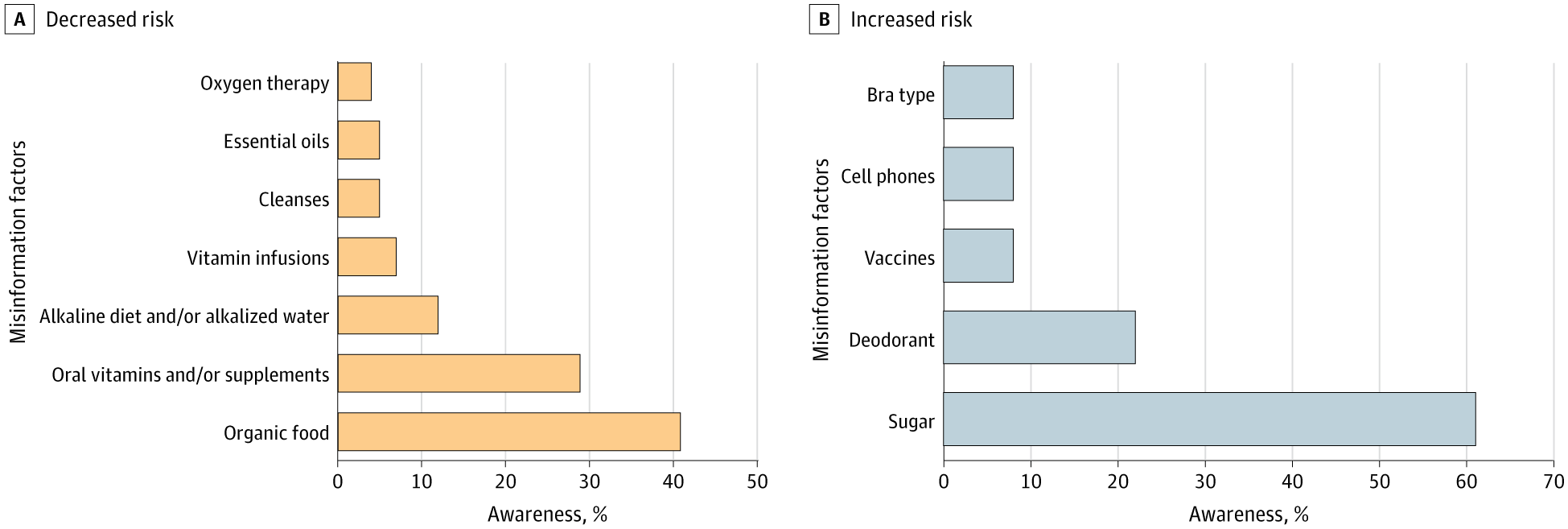

Misinformation Common Among Women With Breast Cancer

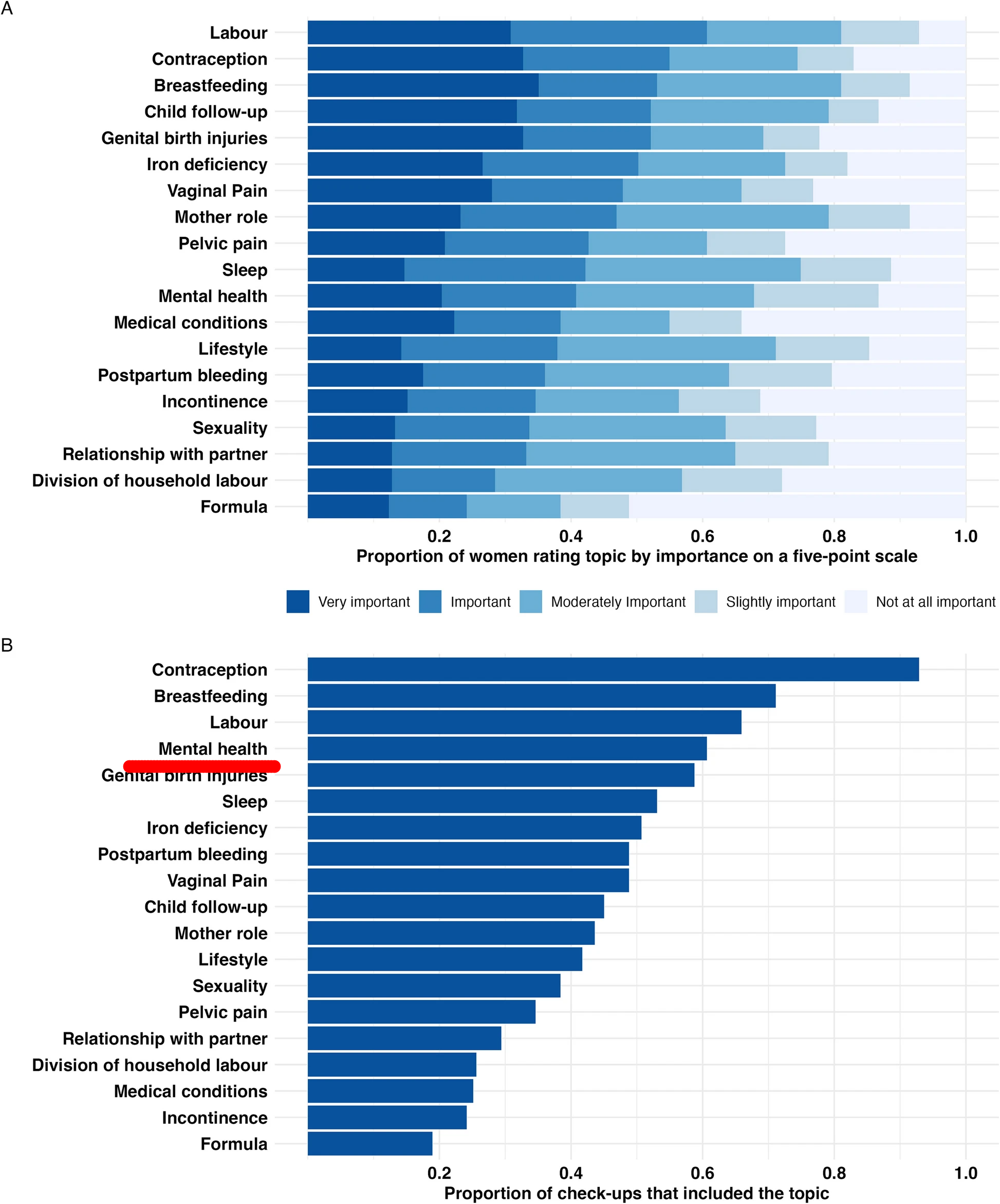

Misinformation Common Among Women With Breast Cancer Even With Universal Health Care, Mothers Don't Go To Postnatal Check-Ups

Even With Universal Health Care, Mothers Don't Go To Postnatal Check-Ups Happy Twelfth Night - Or Divorce Day, Depending On How Your 2026 Is Going

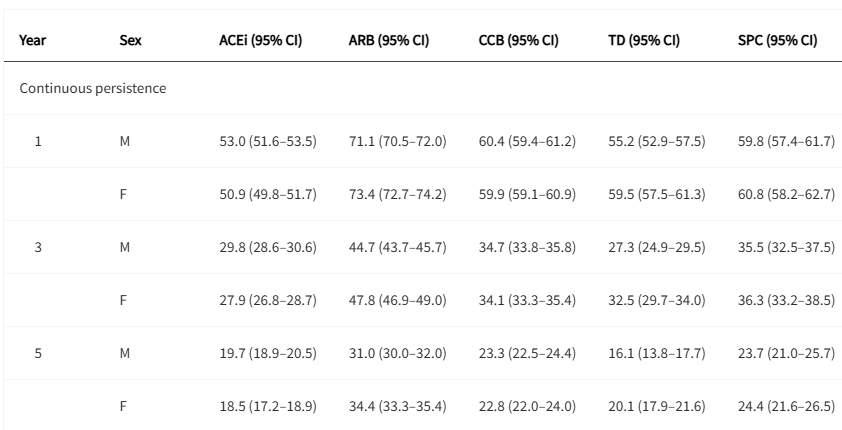

Happy Twelfth Night - Or Divorce Day, Depending On How Your 2026 Is Going Blood Pressure Medication Adherence May Not Be Cost, It May Be Annoyance At Defensive Medicine

Blood Pressure Medication Adherence May Not Be Cost, It May Be Annoyance At Defensive Medicine