Because dogs didn't exist back then, more relevant analogies had to be used in that title. Why? Because analyses of Chengjiang and Burgess Shale food-web data suggest that most, but not all, aspects of the trophic structure of modern ecosystems were in place over a half-billion years ago.

The ecology of Cambrian communities was remarkably modern, say researchers behind the first study to reconstruct detailed food webs for ancient ecosystems. Their paper suggests that networks of feeding relationships among marine species that lived hundreds of millions of years ago are remarkably similar to those of today.

Food webs depict the feeding interactions among species within habitats--like food chains, only more complex and realistic. The discovery of strong and enduring regularities in how such webs are organized will help us understand the history and evolution of life, and could provide insights for modern ecology--such as how ecosystems will respond to biological extinctions and invasions.

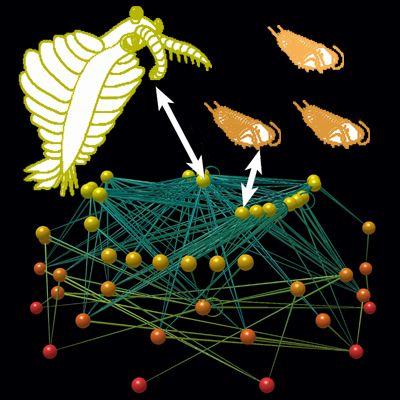

A multidisciplinary group of scientists led by ecologist Jennifer Dunne of the Santa Fe Institute in Santa Fe, New Mexico and the Pacific Ecoinformatics and Computational Ecology Lab in Berkeley, California, studied the food webs of sea creatures preserved in rocks from the Cambrian, when there was an explosion of diversity of multicellular organisms--including early precursors to today's species as well as many strange animals that were evolutionary dead ends. Report co-author Richard Williams of Microsoft Research in Cambridge, UK, developed the cutting edge "Network3D" software that was used for analysis and visualization of the food webs.

The researchers compiled data from the 505 million-year-old Burgess Shale in British Columbia, Canada and the even earlier Chengjiang Shale of eastern Yunnan Province, China, dating from 520 million years ago. Both fossil-rich assemblages are unusual because they have exquisitely preserved soft-body parts for a wide range of species. They determined who was eating whom by piecing together a variety of clues. There was the occasional smoking gun, such as fossilized gut contents in the carnivorous, cannibalistic priapulid worm Ottoia prolifica. However, in most cases, feeding interactions were inferred from where species lived and what body parts they had. For example, grasping claws, swimming lobes, big eyes, and toothy mouthparts suggest that Anomalocaris canadensis, a large, unusual organism with no modern descendents, was a formidable predator of trilobites and other arthropods, consistent with bite marks found on some fossils.

To compare the organization of Cambrian and recent ecosystems, the team used methods for studying network structure, including new approaches for analyzing uncertainty in the fossil data. "Paleontologists have long known that food webs were important but we have lacked a rigorous method for studying them in deep time," comments co-author and paleontologist Doug Erwin of the Santa Fe Institute and the Smithsonian Institution. "We have shown that we can reconstruct ancient food webs and compare them to modern webs, opening up new avenues of paleoecology. We were surprised to see that most aspects of the basic structure of food webs seem to have become established during the initial explosion of animal life."

The Cambrian food webs share many similarities with modern webs, such as how many species are expected to be omnivores or cannibals, and the distribution of how many types of prey each species has. Such regularities, and any differences, become apparent only when variation in the number of species and links among webs is accounted for. "There are a few intriguing differences with modern webs, particularly in the earlier Chengjiang Shale web. However, in general, it doesn't seem to matter what species, or environment, or evolutionary history you've got, you see many of the same sorts of food-web patterns," explains Dunne.

"What we don't know," Dunne adds, "is why food webs from different habitats and across deep time share so many regularities. It could be that species-level evolution leads to stable community-level patterns, for example by limiting the number of species with many predators through selective pressures that result in extinctions or development of predator defences. Or, patterns may reflect dynamically persistent configurations of many interacting species, or fundamental physical constraints on how resources flow through ecological networks."

Answering such questions will break new ground at the intersection of ecology, evolution and physics. And it may provide valuable insights into present-day ecology. As Williams points out, "This research is an excellent example of how computational methods can be used as part of an inter-disciplinary study to help produce novel results. By getting a better idea of how ecosystems behaved in the past, we may better comprehend and mitigate what is happening to ecosystems today and in the future."

Citation: Dunne JA, Williams RJ, Martinez ND, Wood RA, Erwin DH (2008) Compilation and network analyses of Cambrian food webs. PLoS Biol 6(4): e102. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060102

Comments