While it was once believed to be just random bad luck, and modern environmentalists tried to claim it was pesticides in their war against agricultural scientists, the recent problems have instead been varroa mites.

These parasites are just a couple of millimeters in size but they infiltrate colonies and infect bees with viruses and do it will. Yet until their plague on bees got attention in corporate media, so-called Colony Collapse Disorder, there had been little study of the mite's biology.

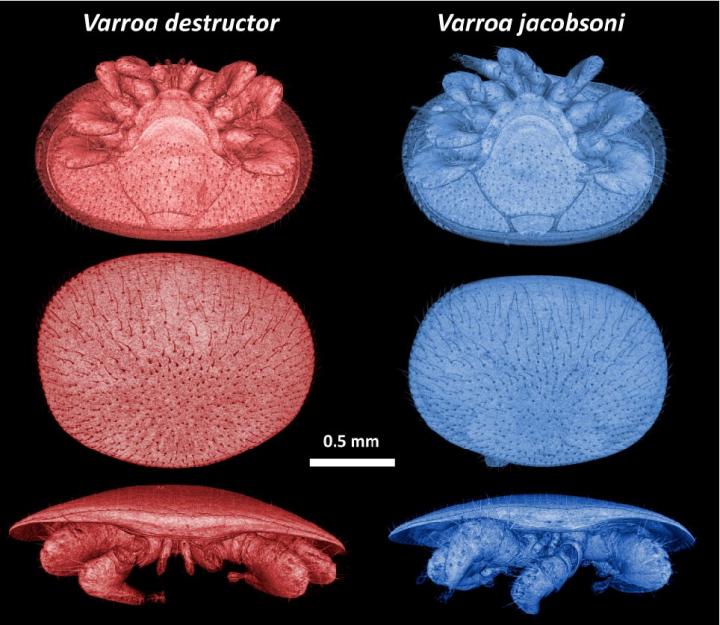

Credit: OIST

Now that has changed.

Researchers from the Ecology and Evolution Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) sequenced the genomes of the two Varroa mite species that parasitize the honey bee. They found that each species of mite used its own distinct strategy to survive in its bee host, potentially overwhelming the bees' defenses. In addition to pointing to how scientists might vanquish these deadly intruders, the findings also shed light on how parasites and hosts evolve in response to one another.

Though environmentalists were wrong in their blaming pesticides, they get create for creating an international effort by scientists to underscore the global nature of the issue parasite issue.

They are an invasive species that came from Asia

Two distinct species of the Varroa mite parasitize domesticated honey bees. Originating in Asia, the mites originally targeted the eastern honey bee but as settlers transported bee colonies across the world throughout the 20th century, the mites spread to Europe, then to the Americas in the 1970s and 1980s, threatening western honey bee populations.

Finally, in the 1990s, a mass die-off occurred due to the viruses, then it happened again a decade later. While environmentalists speculated it had to be pesticides, the culprit turned out to be nature. To better understand how the mites and bees co-evolved over time, senior author Professor Alexander Mikheyev, postdoctoral researcher Dr. Maeva Techer, and their collaborators sequenced the genomes of each of the two Varroa species, finding that they share 99.7 percent of their DNA and appear virtually indistinguishable.

Despite these similarities, genetic evidence indicated that the mite species followed separate evolutionary paths. These divergent strategies of adaptation may make it more difficult for the host species to develop a tolerance to multiple parasites at once.

Mikheyev and Techer hope the sequenced genomes can help lay the foundation for species-specific interventions to address colony collapse, while also furthering scientific understanding of parasite evolution and adaptation.

"It's important to consider that parasites are constantly evolving, and, in many ways, they have a greater potential to evolve than honeybees because they reproduce quickly," Mikheyev said. "As we're trying to fight these parasites, we have to remember that our target is always moving.

When you look outside, every species you see has managed to survive infestation by parasites or diseases. Many organisms haven't met the challenge and have gone extinct. We want to understand the coevolutionary interactions between mites and bees to save the honey bee from such a fate."

Comments