People who eat more calories than they burn on a consistent basis gain weight, and that eventually begins to hinder insulin production, which can mean type 2 diabetes.

A recent study in Diabetologia finds that cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), high-intensity physical activity (HPA) and low sedentary time (ST) are all associated with more normal weight and therefore a lower risk of type 2 diabetes. If you sit around a lot, you will have a great risk for worsened cardiac fitness. There is a genetic factor in cardiac fitness, of course, but the the risk is aggravated by differences in behavior.

This paper used data from 1993 people aged 40-75 years from the Maastricht Study, all living in the southern part of the Netherlands. ST and HPA were measured using an accelerometer device. CRF was assessed using cycle-ergometer testing, with various calculations used to determine power output and oxygen consumption.

The researchers found that higher ST, lower HPA and lower CRF were independently associated with greater odds for type 2 diabetes and also metabolic syndrome (a cluster of factors indicating poor metabolic health, such as high blood pressure and large waist circumference).

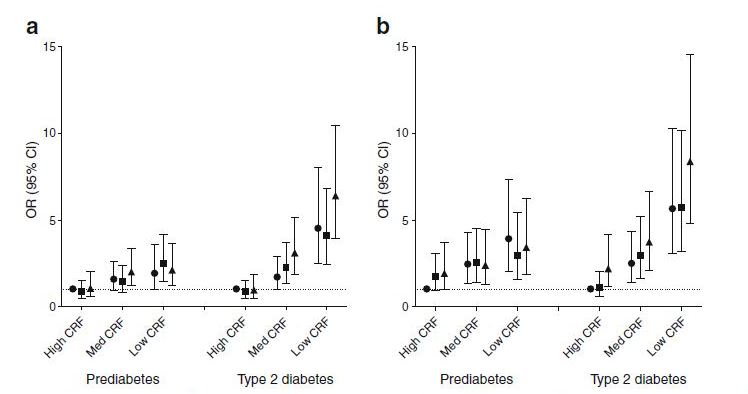

The authors then looked at high, medium and low levels and ST, HPA and CRF in combination with each other. Compared with those who had both high CRF and high HPA, the group with low CRF and low HPA had a 5.7 times higher risk of metabolic syndrome and a 6.4 times higher risk of type 2 diabetes.

Similarly, all subgroups with medium or low CRF had higher odds for the metabolic syndrome, prediabetes and type 2 diabetes, irrespective of ST. Even in those with high CRF, high ST was associated with a trebling of risk of metabolic syndrome and a doubling of risk of type 2 diabetes, suggesting that high CRF may not be enough to 'counteract' the poor health outcomes associated with high ST. This adds to the accumulating evidence that reducing a person's daily amount of ST could be an important part in improving their cardiometabolic health.

The highest risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes was observed in the group with low CRF and high ST; this group had a nine-times higher risk of metabolic syndrome, a trebling of risk of prediabetes and an eight times higher risk of type 2 diabetes when compared with the group with high CRF and low ST.

The authors say: "High ST, low HPA, and low CRF were each associated with several markers of cardiometabolic health and higher risk for the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes independent of each other. A combination of low CRF and low HPA, and a combination of low CRF and high ST, were associated with a particularly high risk of having the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes."

A change from low to medium CRF appeared to be more beneficial than from medium to high CRF, since the difference in risk of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome was higher between low and medium CRF than between medium and high CRF.

Comments