A reader of this blog left an interesting question in the comments thread of the article I wrote on recent ATLAS results two days ago. As I tried to answer the question exhaustively, I think the material might be of interest of other readers here, so I decided to make an independent post of it, adding some more detail.

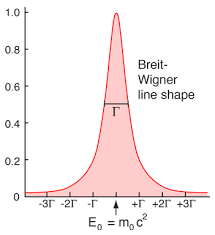

John asks whether it is possible that what we see, when we plot the mass of a particle, is the true distribution of values of the particle - i.e. that the particle does not have only one mass, but a distribution of values. The question is not an idle one! So let us discuss it below. I will make a few points to clarify matters.

1. We estimate by proxy

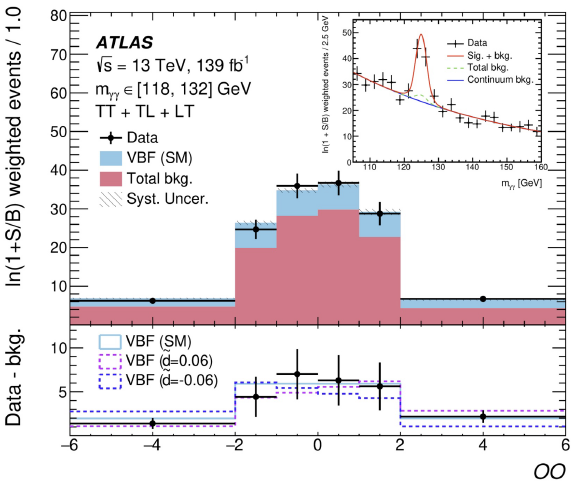

Bill Murray gave a nice summary of recent results from the ATLAS collaboration at the ICNFP conference this morning, and I will nit-pick a few graphs from his presentation to show the level of detail of investigations in subnuclear processes that the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is providing these days, as seen from the lens of one of its two main microscopes, the wondrous ATLAS detector.

The LHC is taking data. What, again?

I arrived to Kolymbari, a nice seaside resort on the western coast of the Greek island of Crete, late yesterday night, and am now already immersed in the morning session of the XI edition of the International Conference on New Frontiers in Physics. This event, which takes place at the Orthodox Academy of Crete in Kolymbari since 2012, takes a rather broad view on advances in both experimental results and theory of fundamental physics.

In over 15 years of blogging, in this and previous sites, I have mostly stayed away from the topic of climate change, the environmental catastrophe we are creating with our "perennial growth" myths and our disdain of our planet and the other species that inhabit it, and the continuous slaughter of over a billion animals every year for our unnecessarily opulent lunch tables.

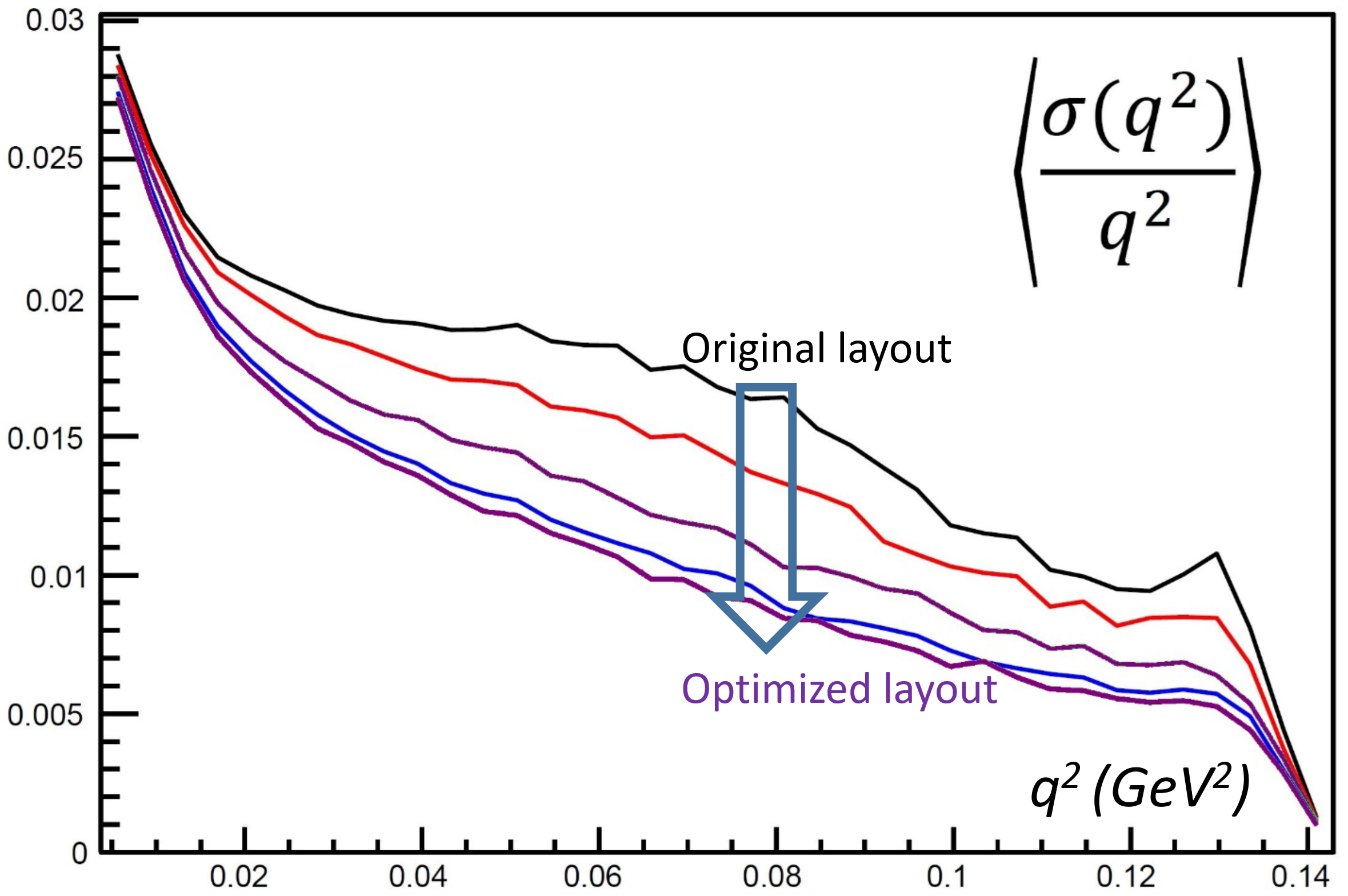

Today I am back from

one of the most interesting workshops I ever attended to, and I wish to share some thoughts I had on possible ways to enhance our research of new ideas for future particle detectors with you. Those ideas come from discussions with other participants to the workshop, or just from re-digesting things I have been pondering over for a while.

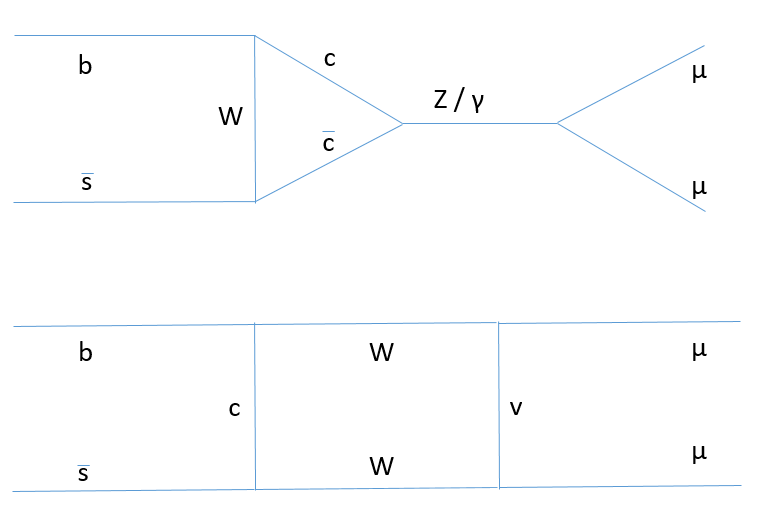

To appreciate what B mesons are, and what is the magic of their behaviour, which is the topic of this article, I need to give you a three-paragraph introduction below.

At the smallest distance scales, matter is made of quarks and leptons, which we consider as point-like objects endowed with different properties and interactions. Most of the matter around us is in fact made up of three-quark systems: protons and neutrons, organized in tightly packed nuclei kept together by the strong force; with electrons (which are the lightest charged leptons) orbiting around them thanks to the electromagnetic force attracting them to the protons.

Shaping The Future Of AI For Fundamental Physics

Shaping The Future Of AI For Fundamental Physics On Rating Universities

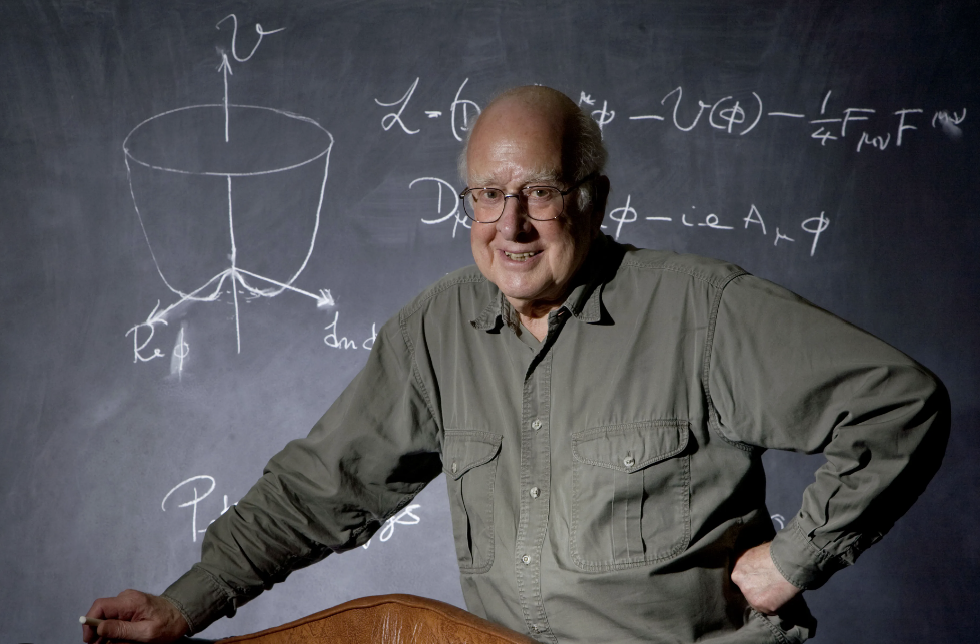

On Rating Universities Goodbye Peter Higgs, And Thanks For The Boson

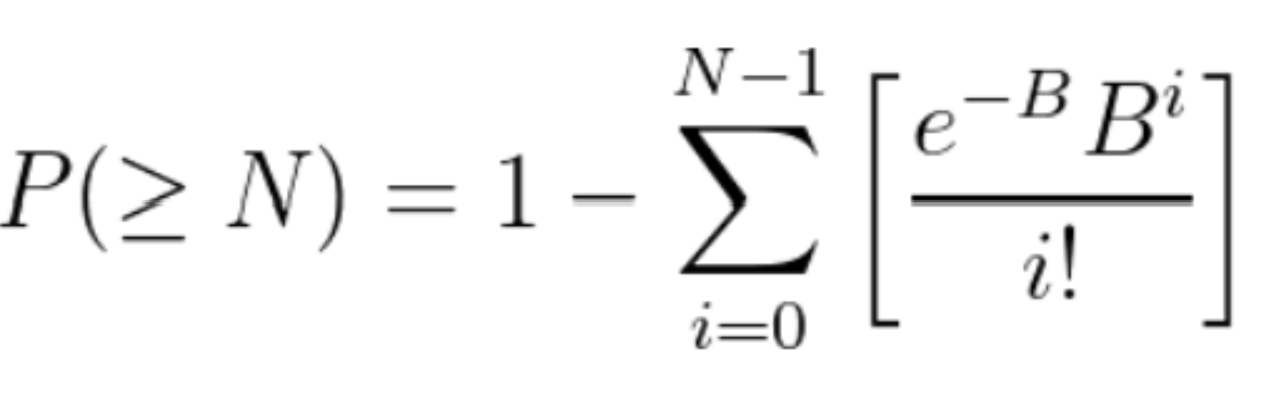

Goodbye Peter Higgs, And Thanks For The Boson Significance Of Counting Experiments With Background Uncertainty

Significance Of Counting Experiments With Background Uncertainty