I thought global warming was all bog-standard, apocalyptic nonsense when it first emerged in the 1980s. People, I knew, like nothing better than an End-of-the-World story to give their lives meaning. I also knew that science is dynamic. Big ideas rise and fall. Once the Earth was the centre of the universe. Then it wasn’t. Once Isaac Newton had completed physics. Then he hadn’t. Once there was going to be a new ice age. Then there wasn’t.

Armed with such historic reversals, I poured scorn on under-educated warmists. Scientists with access to the microphone, I pointed out, had got so much so wrong so often. This was yet another case of clever people, who should have known better, running around screaming, “End of the World! End of the World!” and of less-clever people finding reasons to tell everybody else why they were bad. And then I made a terrible mistake. I started questioning my instinct, which was to disbelieve every scare story on principle...

...if you suspend your prejudices and your vanity for a moment, everything changes.

Actually, this post isn't about global warming. It's about how to figure out what to believe when it comes to science that you're not able to evaluate on your own because you lack the highly specialized technical expertise to judge that particular field. All of us, great scientists included, (Freeman Dyson, I'm looking at you) are frankly clueless about large swaths of scientific knowledge.

So when it comes to a scientific controversy, how do we know which side to bet on? And how do we recognize a genuine scientific controversy, as opposed to a political controversy dressed up in scientific terms?

So when it comes to a scientific controversy, how do we know which side to bet on? And how do we recognize a genuine scientific controversy, as opposed to a political controversy dressed up in scientific terms?It's not an easy problem. Cranks and pseudoscientists, not to mention many of us when we're misguided on occasion, know how to dress up completely irrational views in very scientific sounding language - what sounds, on the surface, like a scientific controversy is really a cultural one. The media sensationalizes minor findings and thus gives dazed and confused readers the impression that major scientific conclusions are completely reversed every year (especially when it comes to the connection between diet and health).

To help you stay on Nature's good side, here are a few rules by which you can navigate the waters of scientific wrangles:

1) Believe the mainstream consensus. I know this sounds boring, but the consensus is your best bet. Yes, it can be wrong. Often, there is no consensus to rely on; but when there is one, it's most likely the best-supported scientific position out there. The mainstream consensus takes time to build, and it is generally not overturned by a single overhyped, recently published paper. We love our underdogs, unfortunately, because we believe in being open-minded and fair. And in fact, the professional scientific community, for its own health, needs to keep them around. But unless you have the expertise to independently judge the arguments for yourself, don't bet on them - just like you don't bet on the bottom-ranked teams in March Madness unless you really know what you're doing.

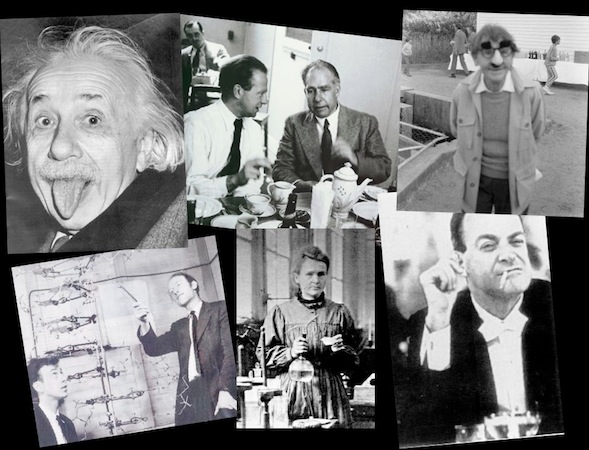

2) Learn to live with ambiguity and uncertainty. On many issues, there is no scientific consensus. That doesn't mean that you now get to pick the theory that most closely fills your emotional needs; it means that we don't know the answer. Don't take my word for it - listen to Feynman:

We absolutely must leave room for doubt or there is no progress and no learning. There is no learning without having to pose a question. And a question requires doubt. People search for certainty. But there is no certainty. People are terrified—how can you live and not know? It is not odd at all. You only think you know, as a matter of fact. And most of your actions are based on incomplete knowledge and you really don't know what it is all about, or what the purpose of the world is, or know a great deal of other things. It is possible to live and not know... (The Pleasure of Finding Things Out, p. 112

3) Contrarianism may be cool, but that doesn't make it right. Especially if your contrarianism violates rule #1.

4) The side that invokes conspiracy theories in any scientific argument is pretty much almost always the wrong side. Individual labs, or, more likely, government or corporate organizations may conspire to suppress research results, but the scientific community at large is incapable of organizing a conspiracy to hide all that great evidence against evolution, global warming, the health benefits of tobacco, etc.

5) Big scientific ideas are always supported by multiple lines of evidence, often from different disciplines. One small finding in one field doesn't take you very far. Evolution is supported by research in molecular biology, biochemistry, developmental biology, population genetics, paleontology, and many other fields. The main consensus in climate change is supported by research in geology, oceanography, atmospheric sciences, etc. These may sound like just words, but in reality, these are very different disciplines - the training is different, the vocabulary is different, the research techniques are different, and generally, an expert in one of these fields doesn't function very well in the other. This takes us back to rule #1: when competitive, obsessive, independent-minded scientists from different disciplines manage to come to a major consensus on something, it's a big deal.

Follow these rules, and you'll go right more often than not.

If you've got more ideas, put 'em up in the comments.

Read the feed:

Comments