Is Your Doctor "Health Blind"?

Is Your Doctor "Health Blind"? There are those among us who are “health blind”, i.e., handicapped at sensing the health signals...

The Ravenous Color-Blind: New Developments For Color-Deficients

The Ravenous Color-Blind: New Developments For Color-DeficientsLast year, as our O2Amp technology got into the hands of more and more users (mainly interested...

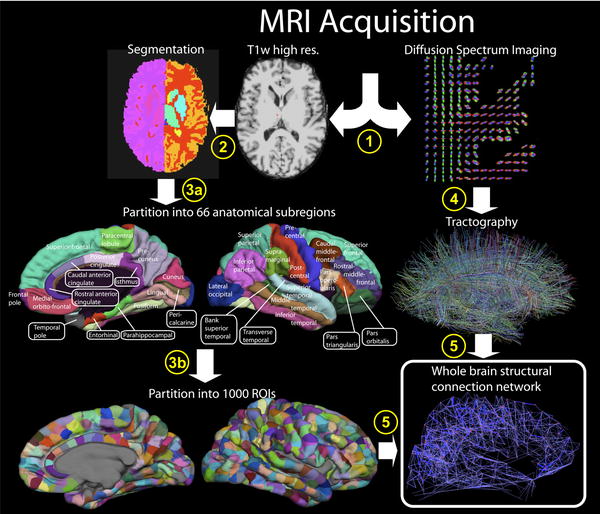

Don’t Hold Your Breath Waiting For Artificial Brains

Don’t Hold Your Breath Waiting For Artificial BrainsI can feel it in the air, so thick I can taste it. Can you? It's the we're-going-to-build-an-artificial...

Welcome To Humans, Version 3.0

Welcome To Humans, Version 3.0Where are we humans going, as a species? If science fiction is any guide, we will genetically evolve...