Using advanced underwater imaging techniques, one of the most detailed analysis ever of the archaeological remains of the lost medieval town of Dunwich - 'Britain's Atlantis' - have been revealed.

The project has provided the most accurate map to date of the town's streets, boundaries and major buildings, and revealed new ruins on the seabed.

Present day Dunwich is a village 14 miles south of Lowestoft in Suffolk, but it was once a thriving port, similar in size to London of the period. Extreme storms forced coastal erosion and flooding that almost completely wiped out this once prosperous town over the past seven centuries.

The decline began in 1286 when a huge storm swept much of the settlement into the sea and silted up the Dunwich River. This storm was followed by a succession of others that silted up the harbor and squeezed the economic life out of the town, leading to its eventual demise as a major international port in the 15th Century. It now lies collapsed and in ruins in a watery grave, three to 10 meters below the surface of the sea, just off the coastline.

The project to survey the underwater ruins of Dunwich, the world's largest medieval underwater town site, began in 2008. Six additional ruins on the seabed and 74 potential archaeological sites on the seafloor have since been found. Combining all known archaeological data from the site, together with old charts and navigation guides to the coast, it has also led to the production of the most accurate and detailed map of the street layout and position of buildings, including the town's eight churches. Findings highlights are:

- Identification of the limits of the town, which reveal it was a substantial urban center occupying approximately 1.8 km2 – almost as large as the City of London

- Confirmation the town had a central area enclosed by a defensive, possibly Saxon earthwork, about 1km2

- The documentation of ten buildings of medieval Dunwich, within this enclosed area, including the location and probable ruins of Blackfriars Friary, St. Peter's, All Saint's and St. Nicholas Churches, and the Chapel of St. Katherine

- Additional ruins which initial interpretation suggests are part of a large house, possibly the town hall

- Further evidence that suggests the northern area of the town was largely commercial, with wooden structures associated with the port

- The use of shoreline change analysis to predict where the coastline was located at the height of the town's prosperity

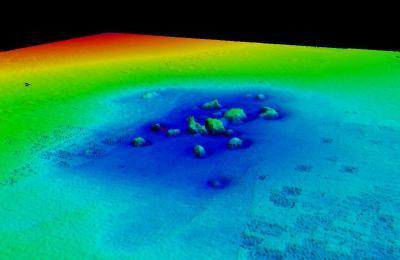

Professor David Sear of the University of Southampton, who led this new project, commented, "Visibility under the water at Dunwich is very poor due to the muddy water. This has limited the exploration of the site. "We have now dived on the site using high resolution DIDSON ™ acoustic imaging to examine the ruins on the seabed – a first use of this technology for non-wreck marine archaeology. DIDSON technology is rather like shining a torch onto the seabed, only using sound instead of light. The data produced helps us to not only see the ruins, but also understand more about how they interact with the tidal currents and sea bed."

3-D visualization of underwater ruins of St Katherine's Church, Dunwich. Credit: University of Southampton

Peter Murphy, English Heritage's coastal survey expert who is currently completing a national assessment of coastal heritage assets in England, says, "Whilst we cannot stop the forces of nature, we can ensure what is significant is recorded and our knowledge and memory of a place doesn't get lost forever. Professor Sear and his team have developed techniques that will be valuable to understanding submerged and eroded terrestrial sites elsewhere."

Commenting on the significance of Dunwich, Professor Sear says, "It is a sobering example of the relentless force of nature on our island coastline. It starkly demonstrates how rapidly the coast can change, even when protected by its inhabitants.

"Global climate change has made coastal erosion a topical issue in the 21st Century, but Dunwich demonstrates that it has happened before. The severe storms of the 13th and 14th Centuries coincided with a period of climate change, turning the warmer medieval climatic optimum into what we call the Little Ice Age.

"Our coastlines have always been changing, and communities have struggled to live with this change. Dunwich reminds us that it is not only the big storms and their frequency – coming one after another, that drives erosion and flooding, but also the social and economic decisions communities make at the coast. In the end, with the harbour silting up, the town partly destroyed, and falling market incomes, many people simply gave up on Dunwich."

Comments