The study is the first to map winter chill projections for all of California, which is home to nearly 3 million acres of fruit and nut trees that require chilling. The combined production value of these crops was $7.8 billion in 2007, according to the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

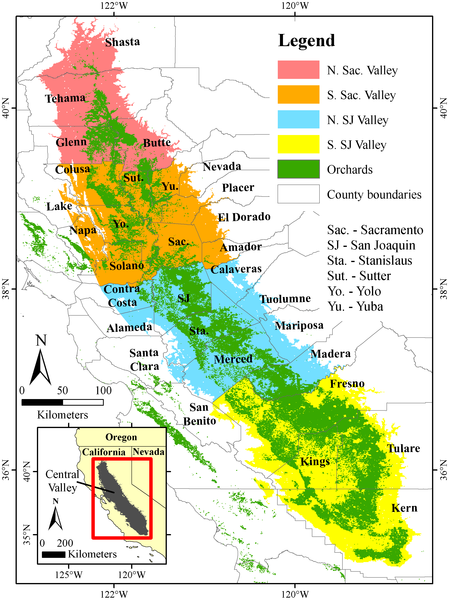

Overview of California's Central Valley, showing the distribution of orchards that require winter chill, the major producing counties and the subdivisions of the Central Valley analyzed separately in this study. PLoS ONE 4(7): e6166. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006166

Why is winter chill important?

Most fruit and nut trees from non-tropical locations avoid cold injury in the winter by losing their leaves in the fall and entering a dormant state that lasts through late fall and winter.

In order to break dormancy and resume growth, the trees must receive a certain amount of winter chill, traditionally expressed as the number of winter chilling hours between 32 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit. Each species or cultivar is assumed to have a specific chilling requirement, which needs to be fulfilled every winter.

Insufficient winter chill plays havoc with flowering time, which is particularly critical for trees such as walnuts and pistachios that depend on male and female flowering occurring at the same time to ensure pollination and a normal yield.

"Depending on the pace of winter chill decline, the consequences for California's fruit and nut industries could be devastating," said Minghua Zhang, a professor of environmental and resource science at UC Davis.

So what is the solution, since wind farms will likely be as useless as they have always been and Californians won't accept the science behind nuclear power?

"Our findings suggest that California's fruit and nut industry will need to develop new tree cultivars with reduced chilling requirements and new management strategies for breaking dormancy in years of insufficient winter chill," said Eike Luedeling, a postdoctoral fellow in UC Davis' Department of Plant Sciences.

Fruit and nut growers commonly use established mathematical models to select tree varieties whose winter chill requirements match conditions of their local area but obviously if those conditions change, tree varieties may have to change also.

The method

To provide projections of winter chill, the researchers used hourly and daily temperature records from 1950 and 2000, as well as 18 climate scenarios projected for later in the 21st century. They then introduced the concept of "safe winter chill," the amount of chilling that can be safely expected in 90 percent of all years. Using those combined hypotheses they calculated the amount of safe winter chill for each scenario and also quantified the change in area of a safe winter chill for certain crop species.

The researchers found that in all the scenarios they used in their models, the winter chill in California declined substantially over time. Their analysis in the Central Valley, where most of the state's fruit and nut production is located, found that between 1950 and 2000, winter chill had already declined by up to 30 percent in some regions.

Using data from climate models developed for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fourth Assessment Report (2007), the researchers projected that winter chill will have declined from the 1950 baseline by as much as 60 percent by the middle of this century and by up to 80 percent by the end of the century.

Their findings say that already by year 2000 winter chill had already declined to the point that only 4 percent of the Central Valley was still suitable for growing apples, cherries and pears — trees which have high demand for winter chill.

The researchers further project that by the end of the 21st century, the Central Valley might no longer be suitable for growing walnuts, pistachios, peaches, apricots, plums and cherries.

"The effects will be felt by growers of many crops, especially those who specialize in producing high-chill species and varieties," Luedeling said. "We expect almost all tree crops to be affected by these changes, with almonds and pomegranates likely to be impacted the least because they have low winter chill requirements."

The research team noted that growers may be able change some orchard management practices involving planting density, pruning and irrigation to alleviate the decline in winter chill. Another option would be transitioning to different tree species or varieties that do not demand as much winter chill.

There are also agricultural chemicals that can be used to partially make up for the lack of sufficient chilling in many crops, such as cherries. A better understanding of the physiological and genetic basis of plant dormancy, which is still relatively poorly understood, might point to additional strategies to manage tree dormancy, which will help growers cope with the agro-climatic challenges that lie ahead, the researchers suggested.

Citation: Luedeling E, Zhang M, Girvetz EH (2009) Climatic Changes Lead to Declining Winter Chill for Fruit and Nut Trees in California during 1950–2099. PLoS ONE 4(7): e6166. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006166

Comments