Here's a development that could have significant implications for electrochemistry, biochemistry, electrical engineering and many other fields: a Nature Materials paper is about computer simulations which find that the electrical conductivity of many materials increases with a strong electrical field in a universal way.

Electrical conductivity is a measure of how strongly a given material conducts the flow of electric current and is generally understood in terms of Ohm's law, which states that the conductivity is independent of the magnitude of an applied electric field, i.e. the voltage per meter. This law is widely obeyed in weak applied fields, which means that most material samples can be ascribed a definite electrical resistance, measured in Ohms.

However, at strong electric fields, many materials show a departure from Ohm's law, whereby the conductivity increases rapidly with increasing field. The reason for this is that new current-carrying charges within the material are liberated by the electric field, thus increasing the conductivity.

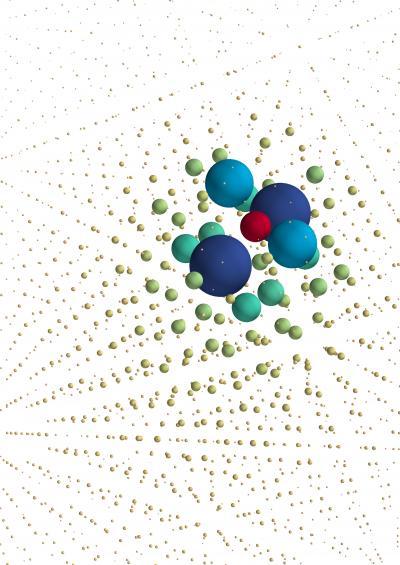

Simulated correlation function for thermally excited charge pairs in a strong electric field. The lattice simulations provide access to atomic-scale details, giving new insights into the universal increase of electric conductivity predicted by Onsager in 1934. Credit: : London Centre for Nanotechnology

The authors investigated the electrical conductivity of a solid electrolyte, a system of positive and negative atoms on a crystal lattice. The behavior of this system is an indicator of the universal behavior occurring within a broad range of materials from pure water to conducting glasses and biological molecules.

Remarkably, for a large class of materials, the form of the conductivity increase is universal - it doesn't depend on the material involved, but instead is the same for a wide range of dissimilar materials.

The universality was first comprehended in 1934 by the future Nobel Laureate Lars Onsager, who derived a theory for the conductivity increase in electrolytes like acetic acid, where it is called the "second Wien effect". Onsager's theory has recently been applied to a wide variety of systems, including biochemical conductors, glasses, ion-exchange membranes, semiconductors, solar cell materials and to "magnetic monopoles" in spin ice.

Researchers at the London Centre for Nanotechnology (LCN), the Max Plank Institute for Complex Systems in Dresden, Germany and the University of Lyon, France, succeeded for the first time in using computer simulations to look at the second Wien effect.

Professor Steve Bramwell of the LCN said, "Onsager's Wien effect is of practical importance and contains beautiful physics: with computer simulations we can finally explore and expose its secrets at the atomic scale.

"As modern science and technology increasingly explores high electric fields, the new details of high field conduction revealed by these simulations, will have increasing importance."

Citation: Vojtech Kaiser, Steve Bramwell, Peter Holdsworth and Roderich Moessner, 'Onsager’s Wien effect on a lattice', Nature Materials doi:10.1038/nmat3729

Comments